Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

News Clippings

Page 1

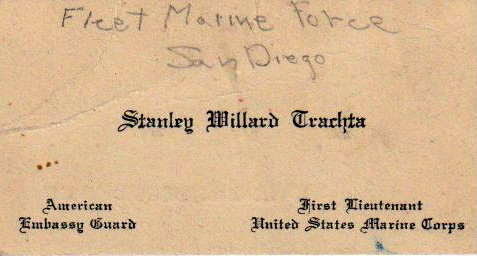

My Dad's older brother, Stanley, was a Pearl Harbor survivor. First Lieutenant Stanley W. Trachta commanded the Marine detachment assigned to the USS West Virginia, a Colorado class battle ship that was part of the fleet shifted to the Pacific in response to Japanese aggression.

The West Virginia's home port was Long Beach, and that is where Stanley's wife and daughter were living. They went to visit him in Honolulu, staying with friends, and Stanley was ashore having breakfast with them Sunday morning, December 7, 1941.

Six aerial torpedoes and two bombs struck the port side of the West Virginia and she settled to the bottom of the harbor, the top deck still above water. Stanley's quarters were destroyed. His wife's visit might have saved his life. Uncle Stanley's 75 Marines had been mustered on deck for a baseball game. All of them survived, but others were not so lucky.

The USS West Virginia suffered 106 of the 2402 total American deaths from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Afterward, Lieutenant Trachta's Marine detachment, plus another 25, were sent as a security force to Maui. Two-man Japanese submarines were tossing shells at an experimental Naval drone operation there, and Pearl Harbor sent the Marines over to help. Within a few weeks he returned to Pearl to join the officers assigned to raise the West Virginia. A massive wooden patch was attached to the port side, the water was pumped out, and the ship refloated. It was moved to a dry dock at Pearl to be readied for a trip to Bremerton Shipyard in Seattle for complete overhaul. The entire Pearl Harbor area was a large salvage operation. The damage to the fleet was extensive.

My father had a camera lens given him by Stanley. The glue holding the glass elements in place was partially dissolved, distorting the focus. My father told me the lens had been in Stanley's quarters on the West Virginia and was corroded by seawater. Some personal property was repatriated during the salvage operation, but it is likely Stanley, as one of the officers managing the West Virginia restoration, recovered it himself.

The above pictures show, top,left to right, the West Virginia viewed from the deck of the Tennessee after the flames were out, and an aerial view of Battleship Row as taken from a Japanese aircraft; bottom, the crew of the Tennessee battling flames on the West Virginia. The West Virginia had been outfitted with radar in 1940. Notice the radar antenna on the foremast.

Page 2

The West Virginia hosted heroes at Pearl Harbor. One notable was Doris Miller, Mess Attendant 2nd Class, and the ship's heavyweight boxing champion. He went on deck to assist carrying wounded sailors to safety. He and Lieutenant Commander Doir C. Johnson, got ship's Captain Bennion out of harms way, before the captain died of his wounds. Doris Miller took over a 50-caliber, Browning antiaircraft machine gun and fired on the attacking airplanes. A black man from Waco, Texas, Miller had received no weapons training in the segregated navy, but managed to shoot down three, or maybe four, enemy aircraft. Score keeping is a gentleman's game, and war is not. Miller received the U.S. Navy Cross for his heroism. It has been speculated that a white man might have received the Medal of Honor. He later went missing, presumed dead, November 24, 1943, when the USS Liscome Bay was torpedoed near the Gilbert Islands. The ship's bomb magazine exploded and the Liscome Bay sank with enormous casualties.

During the West Virginia salvage operation, the bodies of 66 sailors were found below decks. Some had been killed outright and some had found small air pockets, managing to survive for a while. The grimmest of these discoveries involved three sailors who had found an air bubble in a forward storeroom. When the salvage crews entered, six months later, they recovered the bodies of Ronald Endicott, Clifford Olds, and Louis Costin. The men had found flashlights, batteries, emergency rations and fresh water in a battle station. Most troubling, they had found a twelve-by-fourteen inch calendar, on which the days had been crossed off with a red X from December 7 until December 23. They had survived for at least two weeks after the ship sank, trapped at the bottom of the harbor, probably wondering what had happened.

The West Virginia had been scheduled into Bremerton Navy Yard for overhaul prior to the attack. The schedule had been pushed back several times because of rising international tensions in the Pacific. A week after the attack it was decided to refloat and salvage the West Virginia. Enormous wooden cofferdams were built and lowered over the port side. They were fastened in place and sealed with tremic cement. Water and debris were pumped out and she was towed to Drydock No. 1 at Pearl Harbor in early June, 1942, just as Admiral Nimitz was decimating the Japanese fleet at Midway. By May 7, 1943, the ship left for Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington for its long delayed overhaul. It rejoined the fleet in 1944.

Page 3

But what of the three men who'd managed to survive so long? The official record is almost silent on their ordeal. They were listed as killed in action on December 7, 1941. Two are buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. One is buried in his hometown in North Dakota. Their headstones all list December 7, 1941, as their date of death.

Rumors of their plight leaked out slowly. Their siblings met Pearl Harbor survivors who told them what had happened. No one seems to have attempted setting the official record straight, probably because of the horror of the truth. A story appeared in a newspaper. Other written accounts have appeared with the slim facts of the tale. The one artifact that attested to the sailors' sad and gruesome end, the calendar with the days marked off, has apparently disappeared. Rumors purported to come from members of the salvage crew, say it was forwarded to the Chief of Naval Operations, and never seen again. Was it destroyed, or did it drop into some never-reviewed archival hole, or was it quietly put aside in the personal effects of someone in that chain of custody?

The Chief of Naval Operations during the Pearl Harbor attack was Admiral Harold R. Stark, who had himself been captain of the West Virginia from 1933-1934. Stark was replaced in March 1942 by Admiral Ernest J. King, as a result of the post-Pearl enquiries.

Commander Paul Dice’s May, 1942 salvage report has this to say about discovery of the bodies. "Three bodies were found on the shelf of storeroom A-111, clad in blues and jerseys. This storeroom was open to fresh water pump room A-109, which was apparently the battle station assigned to these men. The emergency rations at this station had been consumed and the manhole cover to the fresh water tanks had been removed. A calendar which was found in the compartment had an "X " marked through each day from December 7, 1941, through December 23rd, inclusive. "

In addition to the calendar, Dice found an eight-day clock, which he kept, and later donated to a museum in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Roger Hare, of Auburn, NY, says it this way: "Commander Paul Dice mailed the infamous calendar to Chief of Naval Personnel in Washington, D.C., where it was lost. Bernard Cavalcante (head of Operational Archives for Navy History) has looked for it for 32 years. It remains elusive. A Seth Thomas 8-day clock, retrieved from the pump room was taken by Dice, perhaps as a memento. In later years, Dice donated it to West Virginia's Museum at Parkersburg, where it resides today. " The disposition of the calendar remains a mystery.

The somberness of this tale grows with details from the living. In the days after the attack everyone who worked near the ship, guards, salvage planners, cleanup crews, knew there were survivors trapped below. The men banged on the metal structure to signal they were alive. Their message was heard but nothing could be done. The area was awash in fuel. Munitions were stored and strewn everywhere. Many other ships lay damaged, awaiting repair. The West Virginia, and its sunken neighbors, were an explosion and capsizing hazard of unknowable volatility. Any attempt to breach the hull could have ignited explosions, causing further flooding and damage. And, there was a war going on. More attacks were expected. Sadly, trapped sailors didn't rise to the top of the moment's desperate priorities.

Page 4

If this were a fictional account, or a movie, the trapped sailors would be tapping out messages in Morse Code. We would have Bruce Willis, or John Wayne, or Henry Fonda, abetted by Helen Mirren or Rita Hayworth, carrying out a rescue. Reassuring plans would be tapped out in response to the hapless pleas for help. The men would be rescued in the nick of time.

In the real world, in which the war and its casualties actually occurred, John Wayne didn't appear. The heroes of the West Virginia are left to haunt our conscious and sleeping souls in all their unmitigated reality, and we are left to make of their ordeal what we can. We lift our gaze and say, "Salute," and remember them, and their many silent comrades in our own silent aspirations for the future.

The West Virginia rejoined the war, had more adventures and more casualties. In the iconic picture of Japanese surrender on the deck of the Missouri, the West Virginia stands in the background, proud and silent, in its moment of history. It was decommissioned in 1947, sold for scrap and dismantled.

Ageless winds breathe over the graves of Ronald Endicott, Clifford Olds, Louis Costin, and thousands of others, including the spot in the Pacific where Dorie Miller vanished. My Uncle Stanley and most of his fellow survivors are also now gone. The lasting value of their sacrifices, timeless though it be, is for each generation to affirm anew. Salute.

Click to Hide

John Latko and Bill Moore

Jim Hackworth of Knoxville, Tennessee, alerted me to this story about one of the US Marines onboard the USS West Virginia. John Latko was a Marine in my uncle Stanley's security detail, and, along with the rest of the detachment, had mustered on deck for shore leave to attend a picnic and play baseball. While they waited for morning colors, so they could leave the ship, Japanese airplanes attacked.

Pvt. Latko attempted to man his gun, but the West Virginia was tied to the Tennessee in such a way that the gun could not be fired without hitting the other ship. He did rescue work on the West Virginia until it sank into the harbor mud. He leapt onto a motor launch, a 20 foot drop, without breaking any bones, and assisted in harbor rescues.

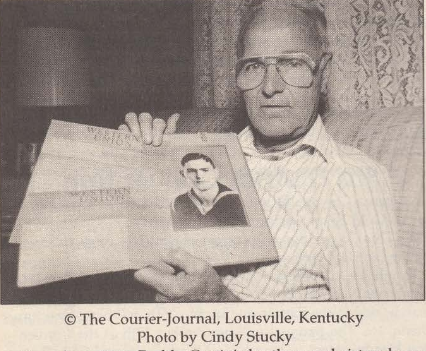

The very famous picture of a whale boat fishing a sailor from the harbor shows John Latko at the bow throwing a line to Bill Moore, in the flaming water of Pearl Harbor. Moore survived but underwent 3 years of medical treatment and surgery. The two men didn't know each other for 50 years until they met at a Pearl Harbor Survivors' Reunion.

John Latko lived to be an old man, passing away in 2013 at the age of 91. He lived in Hammond, Indiana, where a street was named for him, posthumously. The images on this page link to stories about John and Bill Moore.

Who in the world cares about this page?