Click to Hide

King Oliver in the Groove(s)

King Oliver in the Groove(s)

By

Nat Hentoff

Updated July 25, 2007 11:59 pm ET

When I was in my teens, reading about the storied sites of early jazz, I envied the Chicagoans of the 1920s who were hip enough to spend nights at the Lincoln Gardens café where King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band was in residence, recently joined by Oliver's young New Orleans protégé, Louis Armstrong. But the few recordings I could find sounded as if time had worn the music down and dim, including the clicks and scratches of those used early discs.

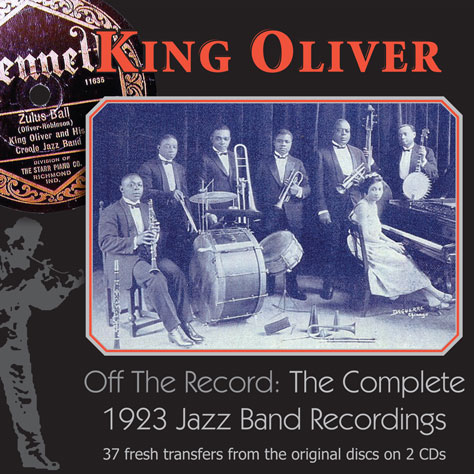

Now, however, in a remarkable feat of sound restoration, 'King Oliver/Off the Record: The Complete 1923 Jazz Band Re-Recordings' (archeophone.com, also at Amazon.com) makes it very clear to me why among the regulars in the audience back then were the young white jazz apprentices who -- according to Lil Hardin (the pianist in the band) -- thronged to hear King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band whenever they played in Chicago:

"They'd line up 10 deep in front of the stand -- Muggsy Spanier, Dave Tough, George Wettling -- listening intently. Then they'd talk to Joe Oliver and Louis." (Also among them were Eddie Condon and 14-year-old Benny Goodman.)

Drummer George Wettling described the excitement in the club in "Hear Me Talkin' to Ya, Dover, " a book published in 1955 that I co-edited with Nat Shapiro: "Joe would stand there, fingering his horn with his right hand and working his mute with his left, and how they would rock the place! Unless you were lucky enough [to be there], you can't imagine what swing they got. "

Now we can. David Sager (a recorded sound technician at the Library of Congress) and Doug Benson (a teacher and recording engineer at Montgomery College in Rockville, Md.) created their Off the Record label last year to bring King Oliver's Creole Band back to life. Working on rare original recordings supplied by collectors, Mr. Benson, writes his partner, "began to capture onto the digital domain clean, smooth transfers of the discs, using a wide array of styli. " The actual music was deep in the original grooves -- though until now poorly reissued and reproduced. The 1923 sounds had to be excavated.

While there were distinctive soloists in the band -- clarinetist Johnny Dodds, trombonist Honore Dutrey and, of course, the leader and the newcomer from New Orleans who would eventually swing the world -- this was essentially a dance band.

In his exceptionally instructive notes, Mr. Sager explains: "That the Oliver band's sound was replete with marvelous invention, and a superior 'hot' sound, was the added premium. The principle, however, was rhythm. "

Joe Oliver never had to announce the next number. As trombonist Preston Jackson recalled, "He would play two or three bars, stomp twice, and everybody would start playing, sharing with the dancers the good time they were having. "

"After they would knock everybody out with about forty minutes of 'High Society,'" Wettling said, "Joe would look down at me, wink, and then say, 'Hotter than a forty-five.'"

Years later, I would hear from musicians who had been at the Lincoln Gardens about the always startling, simultaneous "hot breaks" Armstrong and Oliver played. (A "break"" is when the rhythm section stops and one or more horns electrify the audience for a couple of measures.)

Among the 37 numbers in the two-disc set, these legendary "breaks" can be heard on "Snake Rag, " "Weatherbird Rags, " "The Southern Stomps, " and "I Ain't Gonna Tell Nobody. "

Energized by joining the players and dancers at Lincoln Gardens, I remembered a night long ago at Preservation Hall in New Orleans where, in another "hot" dance band, trombonist Jim Robinson lifted me into joy. What Oliver and Armstrong brought from New Orleans to Chicago, and then to the rest of the planet, exemplified how Robinson also felt about his New Orleans birthright: "I enjoy playing for people that are happy. If everyone is in a frisky spirit, the spirit gets into me and I can make my trombone sing. If my music makes people happy, I will try to do more. It gives me a warm heart and that gets into my music. " Oliver and Armstrong felt the same way.

Since the members of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band were driven by the desire to keep the dancers and themselves happy, hearing them as they were at Lincoln Gardens provides a keener understanding that this music began in the intersecting rhythms of the musicians and the dancers' pleasure.

And in all the different forms jazz has taken since, when it ain't got somewhere that makes-you-want-to-move swing, it may impress some critics with its cutting-edge adventurousness, but it's not likely to make anyone shout -- as King Oliver's banjoist, Bill Johnson, did one night at Lincoln Gardens -- "Oh play that thing! "

In his deeply researched article on King Oliver in the Summer 2007 issue of the invaluable American Legacy: The Magazine of African-American Life and Culture, Peter Gerler notes that after Lincoln Gardens was destroyed in a fire on Christmas Eve, 1924, Joe Oliver brought a new band, the Dixieland Syncopaters, into the Plantation Café, which like Lincoln Gardens "was a 'black-and-tan' club, where crowds of blacks and whites mingled, danced, and enjoyed the music of top black bands. " A Variety review of the new King Oliver band exclaimed: "If you haven't heard Oliver and his boys, you haven't heard real jazz. . . . You dance calmly for a while, trying to fight it, and then you succumb completely. "

Now that Messrs. Sager and Benson have brought us inside the Lincoln Gardens, their coming attractions on their Off the Record label include 1922 recordings by Kid Ory, the New Orleans king of the "tailgate trombone"; long unavailable sessions by Clarence Williams's Blue Five (with Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet); and the classic Bix Beiderbecke sides on the Gennett label. There are more to come.

Messrs. Benson and Sager have been friends since junior high school, where both played in the trombone section of the school band. Mr. Benson also plays bass and piano, and is a composer and arranger. They have now parlayed their lifelong enthusiasm for this music into a permanent sound library of historic jazz performances freshly retrieved from inside the original grooves.

With regard to what's ahead on their label, Mr. Sager says eagerly: "It will be interesting to see what technology enables us to do in the coming years. " I yearn to listen to Bix Beiderbecke directly, so I can hear what Louis Armstrong heard: "You take a man with a pure tone like Bix's and no matter how loud the other fellows may be blowing, that pure tone will cut through it all. "

Mr. Hentoff writes about jazz for the Journal.

The image links to Archephone Records, where you may get your own copy of these re-recordings. You'll want to check out the Bix Beiderbecke release as well. You can hear samples, but Bix can't be purchased from Archephone anymore. Sometimes you find a copy on the used market.