back to the attic

back to the attic

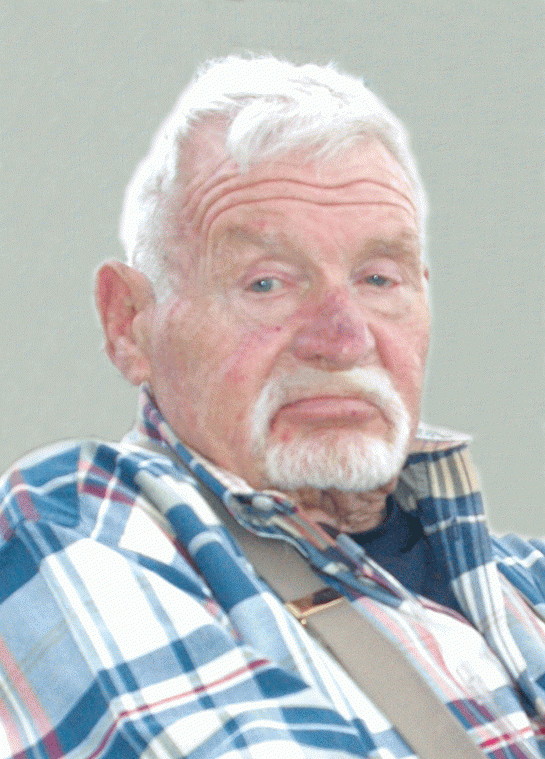

Harry was a storyteller, the Homer of Apollo. We met in the mid-70s, sharing a cubicle at the NASA Slidell Computer Complex, both of us starting new lives. He was a NASA pioneer trying out as an executive, and I was in a holding pattern developing performance models for the new Univac 1108. He had endless, mesmerizing tales that demanded attention. He could talk and work, but I wound up working overtime. Oh, those stories.

A veteran of the Gemini and Apollo days, he'd worked among the era's superstars, and their ghosts ambled between our desks as I puzzled out queuing algorithms and he wrote technology plans. Rustic and non-degreed, Harry conjured images of a battered pickup truck and a Bluetick Hound. He owned both, and many of his stories referenced adventures in the Honey Island Swamp, where his peers tended crab traps and chopped pulpwood. Frank Lavatto, systems programmer from Dalhart Texas and a curiosity in his own right (He'd pore over a core dump and announce the computer had been, "Flying on with its heart shot out!"), summed Harry up as, "A dumb old country boy with an IQ of about 160." The boys from Dalhart know a thing or two.

Harry loved joking and teasing, and worked hard to avoid seriousness, although he was always sincere. When a colleague expressed excitement that the Ivory Billed Woodpecker might have survived extinction in the swamps of Mississippi, Harry studied a picture of one and nodded, "Yep. I've killed a many of them." One day the main gate informed him the local Sheriff was waiting with an arrest warrant. Everyone knew the warrant was for another Harry Smith, but Harry had a good time with the sheriff before letting him discover his mistake.

The above picture of the Apollo 15 mission, with the Lunar Rover deployed and the Lunar Module in the background, is linked to a retrospective of the importance of the rover.

For a year and a half he shared his fabulous stories. He'd manned tracking sites in the Pacific, and worked at Johnson Space Center. His vivid portrayals of larger-than-life characters sounded fantastic, but Harry had the credibility of a rhapsode talking of Troy.

He was a kindred spirit, catching and sharing the humor of the many subtle instances of folly that swirl through the average workday. We'd leave a meeting with Harry's soto voce impersonation, "Mmph mmph…poor plotting techniques," as we spun some fantastic version of what had just occurred.

A few years later Harry left for better things, but it didn't go well. His tolerance for idiots ran out, so I heard. He bounced around and I lost touch with him.

Then occurred one of those serendipities life tosses when you're looking the other way. A seeming shipwreck washed me ashore at Johnson Space Center. There was an eerie familiarity about the place. I'd never worked there before, but I recognized people. I'd met them in Harry's stories. Time after time the characters from tales in that little cubicle near Lake Ponchatrain introduced themselves. It was like seeing old friends I couldn't remember meeting.

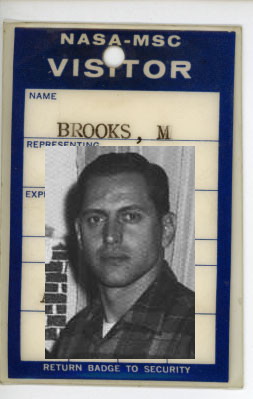

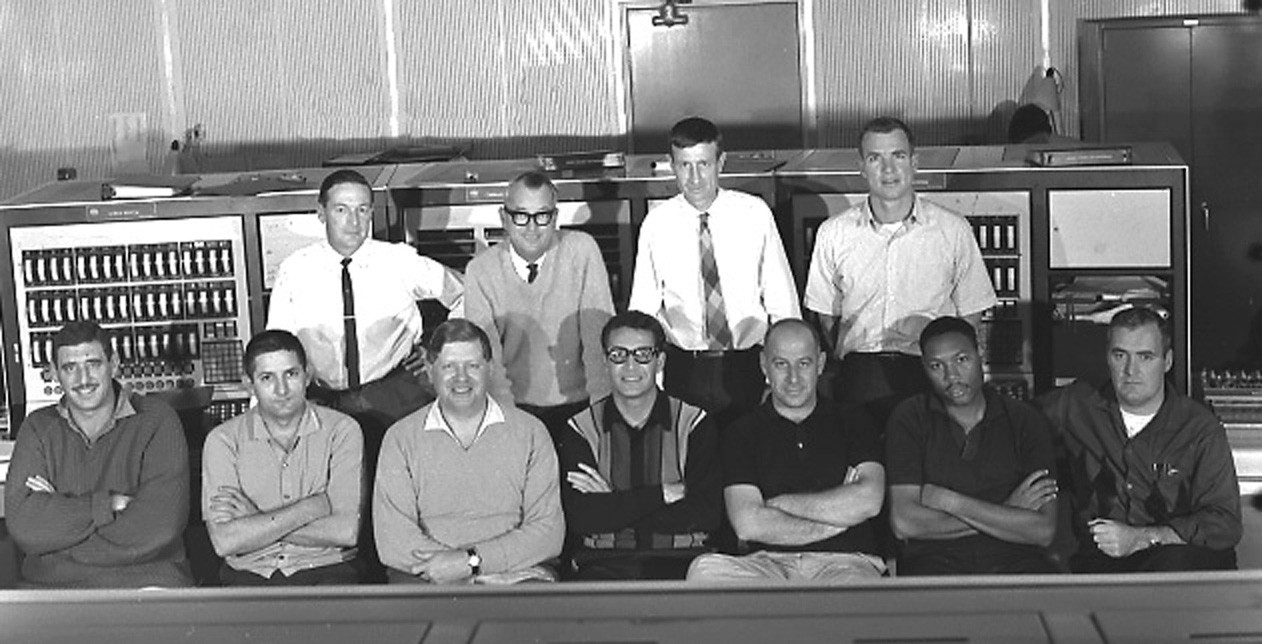

Harry at Carnarvon Tracking Station for Gemini 4, front row, second from the left. Back right is astronaut David Scott, front third from right is capcom Ed Fendell, a prominent figure in Harry's stories. The pictures are from Hamish Lindsay, and this and others are further identified in the popup link.

There was the guy who'd informed Gene Kranz, from a remote tracking site in the Pacific, that he would keep Gene's latest management dictate at eye level in his outhouse, right where it belonged. There was the headquarters building where one of the astronauts rappelled off the roof as the bemused center director watched from his office. There was the Building 1 flagpole where someone, maybe John Llewellyn, tied his horse after being banned from driving on base. There was the control center where veterans surreptitiously blew cigarette smoke through a length of plastic tubing, causing it to emerge from the console of a novice flight controller. There was "Captain Reduction," who could shrink any graphic to fit any space.

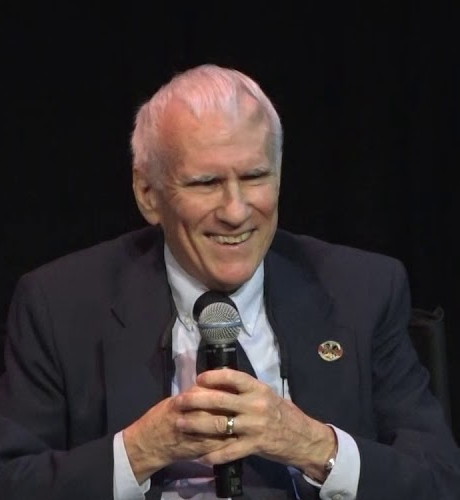

This reunion of Apollo-era flight controllers in the restored mission control center features several of the characters from Harry Smith stories, including Ed Fendell, third from left, and Gene Kranz, fourth from left. The image links to a popup page about Harry's time at the MCC, before I met him at Slidell.

There was the giant display where JSC controllers watched a live feed from the cape, where someone arranged to play an actual launch during a dry run, causing Gene Kranz to jump up shouting, "You see that!!?" as the vehicle flew off into space. Gene collected himself and pointed at the grinning culprit with, "I have a long memory!" And, there were numerous people who'd either known Harry, or verified the truth of his stories. Here was the guy who'd been with Harry the night he was nearly killed in a car wreck. But there was a difference, too. The whole experience had the feeling of seeing the movie after reading the book. If you were properly aged, it was like seeing the TV show after enjoying the radio broadcast. Things didn't quite measure up to Harry's telling.

This picture of Vince Fleming and Gene Kranz, taken at an Apollo 11 25th Anniversary celebration, links to Mr. Fleming's recollections, including a rare picture of Harry Smith.

But, there was one exception. I walked into a meeting in my early days at JSC chaired by a man I'd never seen before, and who, in those days, had no public persona. I knew him instantly. When he spoke I recognized his voice, and anticipated his phrasing. It was similar to déjà vu, and I struggled to remember where we'd met. Then I realized. He'd materialized into real life from Harry's stories, the images formed at Slidell accurate in detail.

Harry Smith was the only man I've ever known who could tell a Harry Smith story. The only person in the world who could ever live up to one was Gene Kranz, Mr. Mission Operations at Johnson Space Center.

Harry popped up shortly after my arrival in Houston, working for Bendix on the same shuttle operations contract. We reconnected, but lightly. It was a frantic time in those post-Challenger days. And then Harry was sick. And then he passed away.

Gene Kranz delivered the eulogy. He recalled Harry's disdain for "Pogues," Harry's word for those crouched eternally in a CYA posture. Gene quoted Teddy Roosevelt, appropriately, and then, even more appropriately, pronounced Harry, "The world's first flight controller." That's like being named to the Hall of Fame by Babe Ruth.

This picture of Bob Legler links to some recollections by Sy Liebergot in which he mentions Harry Smith.

Not a lot is known about this remarkable man. But other people have remembered him. Harry was born in 1931 in Poplarville, Mississippi. He must have gone to high school in Poplarville, or nearby, but no records have been found. He enlisted in the USAF on 8 January, 1952, and was released 19 December 1955. He returned to the United States from Grand Turk Island, through Key West, on board a USAF C-54, 28 November 1958. His address on returning was listed as New Orleans, 1025 Milan Street. This information supports a theory that he may have graduated from the Air Force Electronic Technician school, a highly respected training program, and that he might have been working on the Eastern Test Range during the 1950s, prior to the formation of NASA. There are records indicating one of those legendary Range Rats was named Harry Smith, but he hasn't been confirmed as our Harry Smith.

Harry is buried in Pearl River County, along with his wife Beth. His aspirations and inner spirituality, he was not religious, remain conjecture. But he appears in the record of space flight, the premier human adventure of the twentieth century, and the references are uniformly positive. That is certainly a spiritual connection.

He was highly respected by those who gave a damn, and no other opinions matter.

We've displayed as links beneath the pictures, some recollections about Harry by those who worked with him.