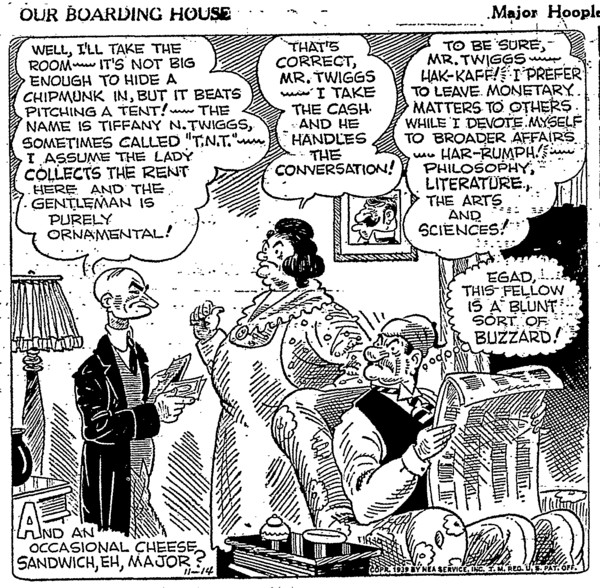

A man for our times, Major Hoople, embodied the marriage of mediocrity and hubris. In fact, he was a man for all seasons.

A significant sliver of society flies hither with its hair afire; another elevates barroom bluster to wisdom. Never mind. Let's ponder more vital fixtures: the funny papers.

The art of the comics flows in two streams, the "dailies" and the "Sundays," linked by tribe, but strung of different ethics. Dailies live on the street, nourished in the ventilations of elan vital. The Sundays are punctuation, reflection and restoration as per the Oxford English Dictionary reference for "sabbatical: 1892 A. Birrell Res Judicatæ ii. 38 A sabbatical calm results from the contemplation of his labours."

Prepare for a dismal truth: the comic art flounders. Our text is from the Austin American Statesman, commended for preserving our American Comics birthright, but alas, far away from funnies excellence. We find thirty-six daily efforts (counting single-frame cartoons), of which about twenty-two are readable. Maybe fifteen of these grow in comic soil, of which a dozen rise to "worthwhile." The rest? Oh dear.

You want socially redeeming value? Is that what you're after? Click the picture.Or maybe you're looking for scholarship?

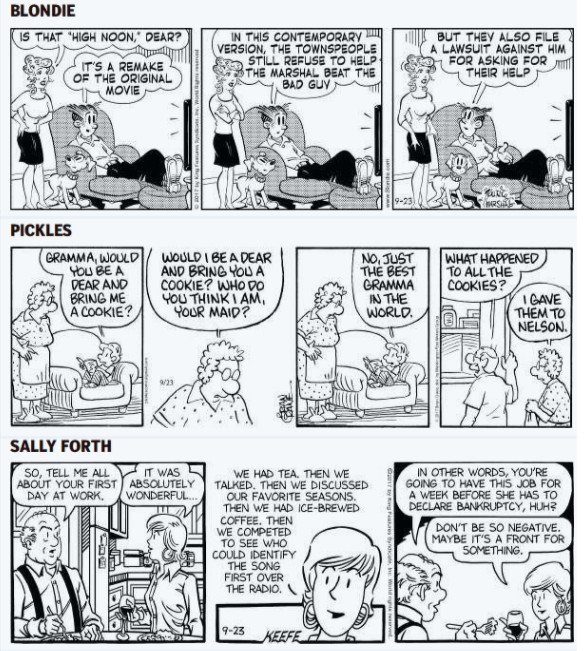

Start at the top. The eye passes over "Baby Blues," and "Baldo," as wasted space, uninspired clichés lacking visual significance. "Mother Goose & Grimm" is readable, but in decrepit dotage. "Garfield" a single gag repeated daily with modest variation retains an existential appeal, like a pet rock. "BC" is a comic in long decline, once the cleverest thing on the page, now a self-conscious slug of reduced expectations. "Blondie" is a classic, preserving a narrow band of artistic expression at once nostalgic and timely. "Red & Rover," and "Phoebe & Her Unicorn," suffer from low self-esteem, humdrum vision, and low integrity. This space on the page, alas, once held the modern classics, "Edge City," and "Cul De Sac," but their retirement has revealed the paucity of the comics-art farm system.

It's out of syndication, but you can still enjoy Edge City. And Cul de Sac.

Comics move in the three dimensions of artistic space: vision, execution and honesty. Classics go deep in at least two of these, but are never just two-dimensional. Alas, the replacements for "Edge City" and "Cul De Sac" draw ciphers in all aspects, myopic, rudimentary and truthless.

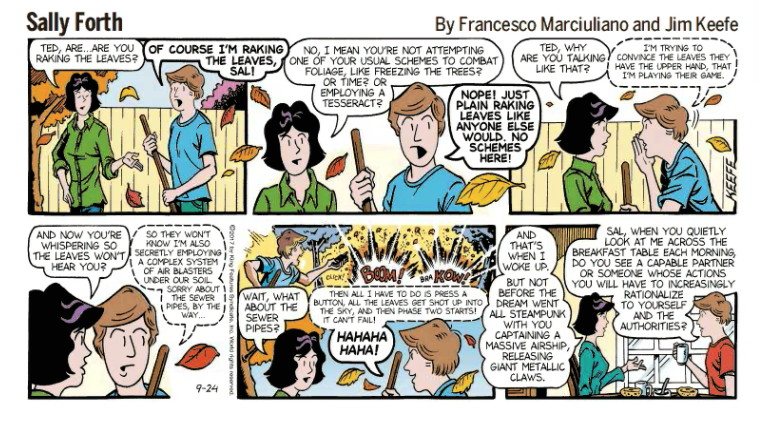

Proceeding through the panels our eye engages "Pickles," a readable but unremarkable strip. "Sally Forth" is a welcome diversion with its multi-character world of contemporary whimsy, featuring understated stereotypes, set pieces, and presentational acting that alludes to the presence of an audience. Next is the often entertaining "Pooch Café," where sentient animals share an overlapping social world with humans. "Born Loser" is so awful as to be almost campy. "Dilbert" retains its vision of destructive office life, although its original swerve has gone straight. "Hi & Lois" excels in the narrow band of adult/child misunderstanding. "F Minus," unreadable, overrates itself. "Jump Start" follows the old traditions of the last century, with wordless exclamation marks, hats flying off, and references to plot lines outside the visual moment. "Frazz", once bright, still readable, now substitutes a mental raised eyebrow for cleverness. "Bizarro" is work-a-day visuals in search of a story. "Non Sequitor" is that boy in high school who believed people underestimated his intelligence. "Ziggy" is the last purple gumdrop no one wants.

On the next page are two political strips in the hair's-afire camp, run together as innoculation against partisanship complaints. "Doonesbury" is a champion of intellectual flabbiness, snickering near the object of its scorn. "Prickly City" imagines itself a send-up of political extremes, but wanders in a twi-light of warm pabulum.

There actually was a comic strip called State of the Union. Like many political strips, it eschewed humor for lathered and sweaty partisanship.

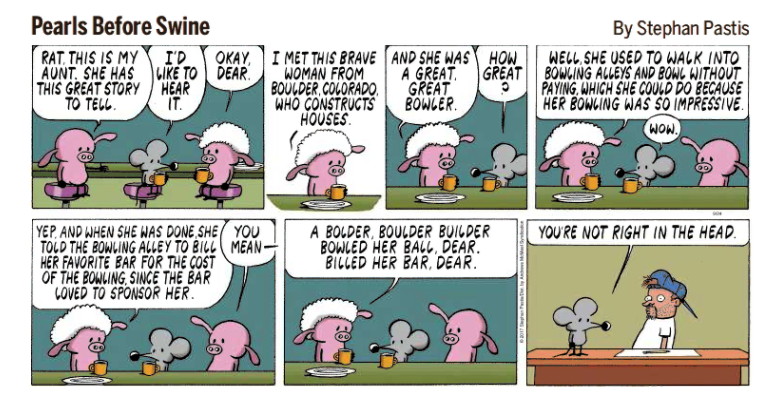

The third page is more readable, and more useful, than the TV viewing schedules nearby, which are as useful as a stove-top flatiron. "Over the Hedge," once full of integrity, now slops through the staggering wander-abouts of politics. Will it ever return? "Pearls Before Swine" is a modern classic: penetrating vision, uncomfortable honesty, good humor, and great execution. Though faded from its original days with antics like Rat's "cap-o-immortality," such flashes sometimes recur. "Wizard of Id" strays often from its shtick, as do a lot of selective-fantasy efforts, but the timing, visual impact and good humor are often there. "Candorville" promises intellectual pound cake, and serves saltine crackers. Too often it slathers in a wilted, ho-hum snipe intended as political message. "Rose is Rose," a brief readable moment, is actually two strips running in the same space, sometimes featuring humans in stock skits, and sometimes animals.

Comic artists are professionals, but amatuers dominate the critics. Here's a blog you might want to see.

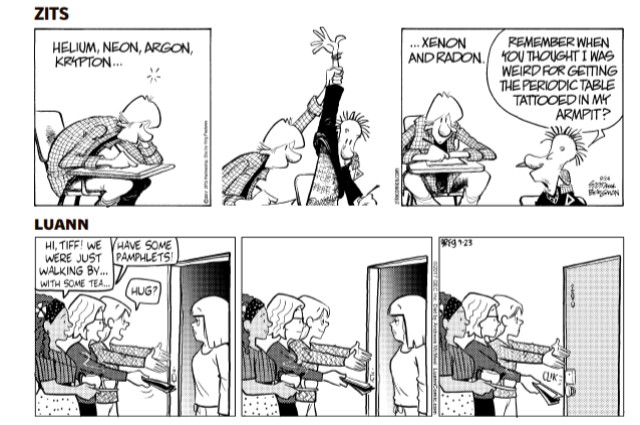

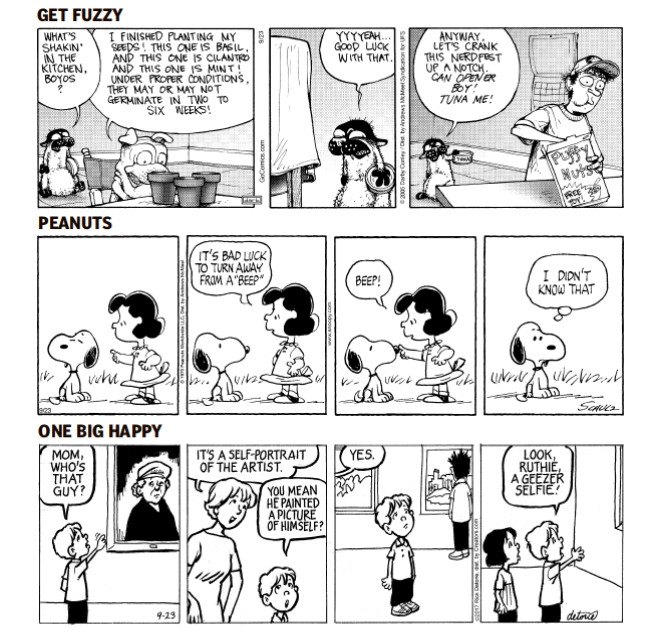

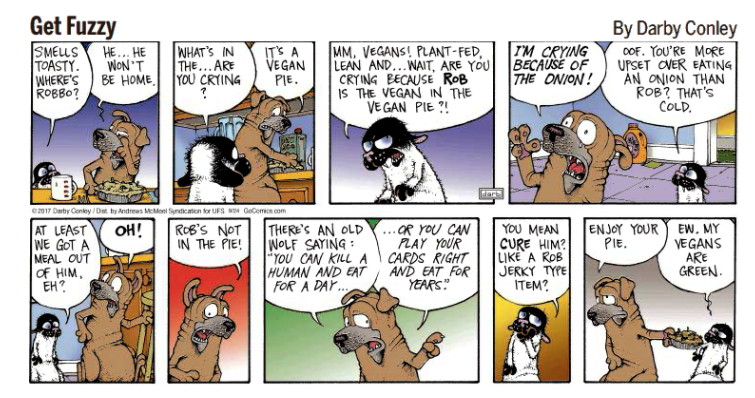

"Mutts" delivers more than it demands, and has a quirky friendliness. "Hagar the Horrible" has departed its creative space, too often thrusting its characters into anachronistic story lines. It would not be missed. "Zits" turns on the antics of a teenaged boy, a fecund inspiration, and usually entertains. "Luann," once a tale of a high school girl, has tried to age into an older setting with college and young adult themes. Its new efforts suffer an integrity deficit, as it drifts toward Garfieldism. "Get Fuzzy" is a modern classic. Its characters bring secure identities, including the inspired bit players who pop in and out. "Peanuts" is a wonderful reminder of what the decades have leached from comic artistry. It was never the best strip during its prime, but now, in perpetual rerun, it dominates. At last we get to the delightful "One Big Happy." Quirky little chidren, equally quirky adults, interact in loving and friendly ways, always delivering a smile.

There is also "Mallard Fillmore," a political comic strip now banished to the puzzle page. It specializes in fingering hypocrisy, a dangerous pastime with such a slippery substance. Like "Doonesbury" and "Prickly City," it's funny if you think it is.

That's it: the daily comics. Not a show for the ages, but apparently the best we can do. Now, about those Sunday funnies, again drawing on the Austin American Statesman, as our purveyor.

The front page of the Sunday comics is a colorful waste. The eye sniffs it like wallpaper samples: lowered expectations and rising disappointment. "Dustin" is plodding nausea; "Stone Soup" a puzzled question, "Why draw this?" Below, "Buckles" rivals the boredom of Mister Tooth Decay. Finally comes the eye-gorging, lavish artwork of "Prince Valiant," asking its everlasting question, "Who reads Prince Valiant?".

The second page features "Big Nate" whose jagged, funny looking artwork recalls classic fare like "Nancy and Slugo." Alas, it is one of those penny candies, attractive but god-awful. The Sunday version of "Pickles" is untaxing, promising nothing, disappointing a little. "Zits," Sunday edition, usually exploits a teenage-boy moment with a barbed hook at the end. "Peanuts" is "Peanuts," clever, thoughtful, and pleasant to swallow. "The Born Loser" is like the sorbet after dinner. It clears the way for "Sally Forth," which usually serves up innovative flourishes in one of its nougaty set pieces.

The next page brings "Jump Start." Seldom worth reading, it often stretches a three-panel idea into the Sunday format. "Frazz" struggles a little harder on Sunday, but a lazy vision holds it back. "Rose is Rose" is usually cotton candy on Sunday. "Family Circus" recalls those old roundabout, swing-era comics that left you inventing more twists that it could have taken. "Dilbert" on Sunday is like daily "Dilbert," except longer, which allows getting closer to the outer limits of office life at its worst. "Luan," usually steps away from its daily drama to revert to some teen/adult generational gap humor.

The third page begins with "Mutts," dogs and cats exploring their anthropomorphic insight. Some thread of logic is carried near, but not quite to, the edge of reality. "Hi and Lois" on Sunday is often an adult imparting some lesson of life, with the youngster's sensible interpretation raising unanswerable questions. "Prickly City" on Sunday is like the daily. It's funny if it's funny. "Phoebe & Her Unicorn" becomes even more forlorn on Sunday, pointless, uninteresting, and now pretentiously chromatic. "Pooch Café" on Sunday, like many Sunday strips, departs from its daily strife to illustrate some misunderstanding between dogs-who-think-and-talk, and their alloparenting humans. "Non-Sequitur" on Sunday is a more strained and fatuous version of its daily authority-meets-the-wise-everyman trope with authority revealed as the naked emperor.

Behind the picture is a link to someone's idea of the 25 best. Agree? And this is a link to a history of the comics.

The next page starts with a grotesquery called "WuMo," a portmanteau of the two artists' names. It screws dreadful drawing into an unfunny take on human foibles. "Baby Blues" is a too-cutesy-by-half strumming of the what-adults-imagine-babies-might-be-thinking guitar. "Pearls Before Swine" on Sunday often indulges an over-wrought, long-windup punmanship, which delivers less than we'd like but more than most. "F Minus" sluices through Sunday, oblivious to its mendacity. "Ziggy" on Sunday is colored, daily "Ziggy," some sight gag that was funny long ago. Sunday "Doonesbury" is often a spectral excursion into a denser part of the cartoonist's skill, but still spoiled by its congenital smirk.

The last page of the Sunday comics starts with something called "The Pajama Diaries," an effort so minimal it underscores absolute zero. "Candorville" on Sunday is an extended, slow-paced sendup of some pop culture artifact that sorely needs ignoring. "The Argyle Sweater" is a Sunday only comic, often a single panel giving the splash treatment to something that could have been mildly humorous if suggested subtley. "Get Fuzzy," like the best of the Sundays, often digresses from its daily plot into some improbable, word-play misunderstanding between the characters, without settling for standard puns, or overwrought constructions. "Over the Hedge" usually batters some sophomoric topic with harsh overtones of smugness. "Garfield" ends the Sunday comics with a sturdier effort than we normally see in the daily, sometimes extending itself beyond its comfortable rut.

Here is one of the many top 10 lists. I'm guessing it's by someone under the age of fifty, who knows the real top 10 only from books.

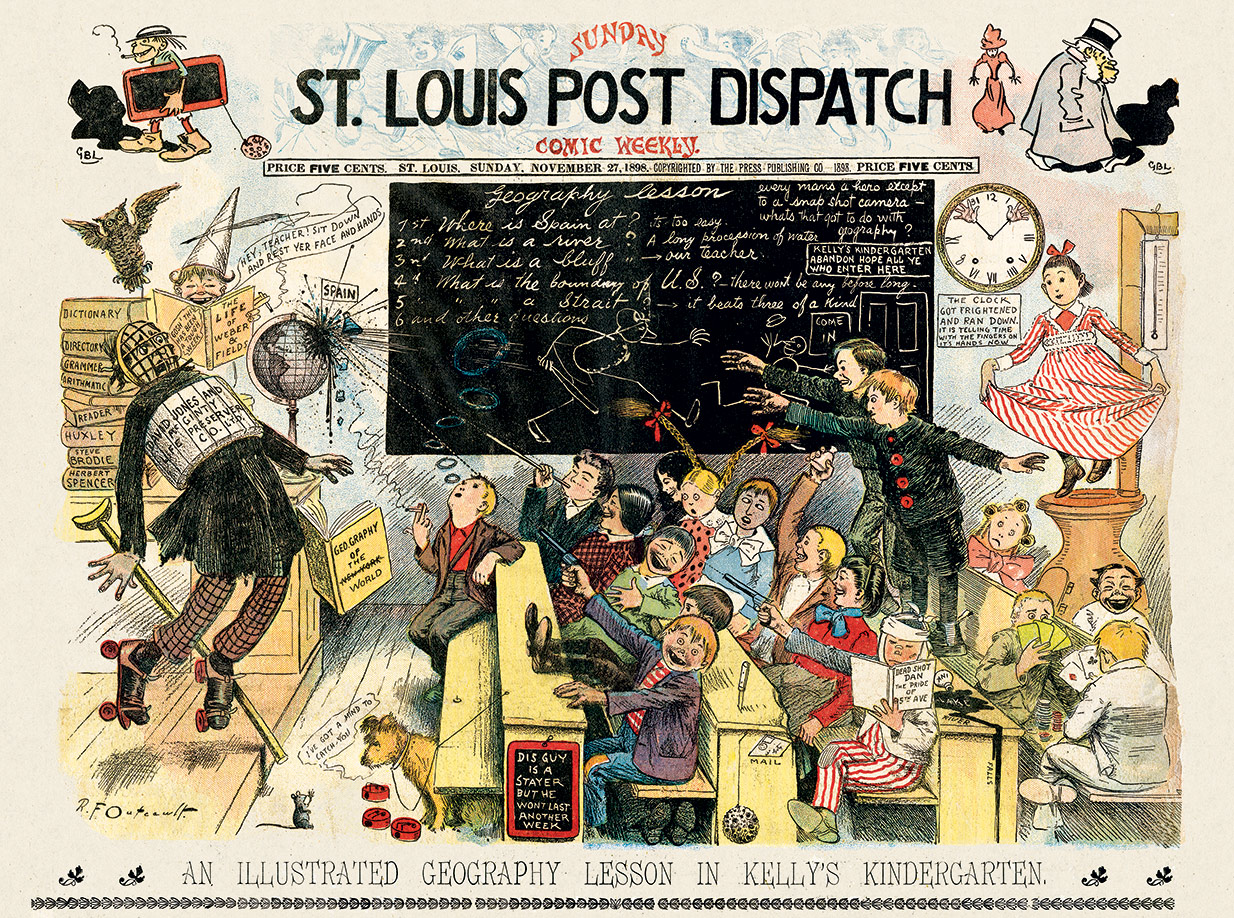

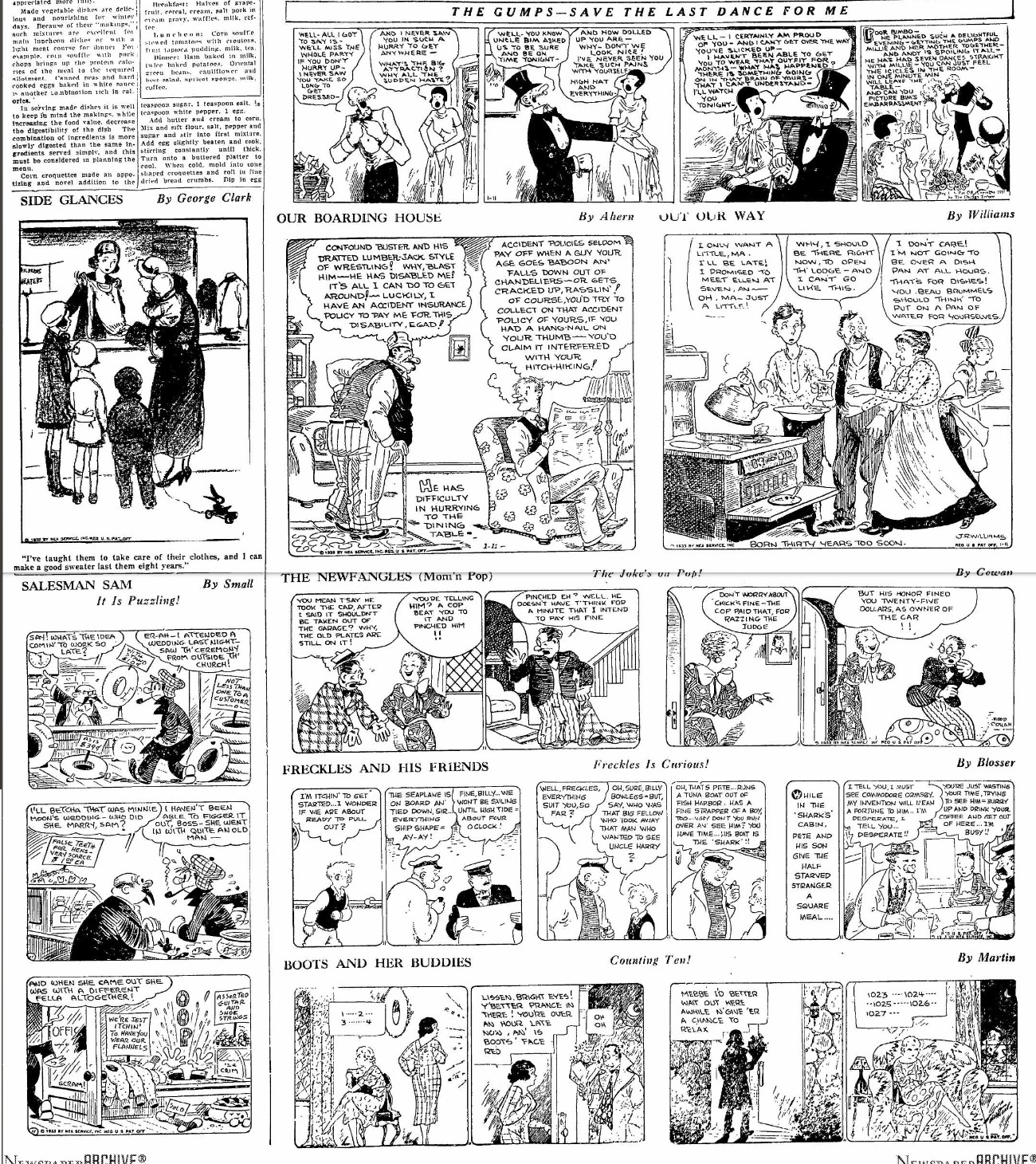

There we are: the state of American Comics. Is it really that bad? In the not-so-long-ago we had such marvelous fare as "Popeye," the "Katzenjammer Kids," "Alley Oop," "Out our Way," "Krazy Kat," "Pogo," "Moon Mullins," "Bringing Up Father," and so many more. How have we fallen to the low state of "WuMo" and "F Minus?" But wait. Is that a fair comparison? Can we compare the standard fare of today with the best of the classic past? No, we can't. If we grab a newspaper from a day out of the past, and take a look at its comics, we find a state of things much like today.

Below is a page from the Helena Independent, Helena, Montana, January 11, 1933. Glance through it. Read it perhaps. There is little here better than today's comics. Alas, comics, like all popular culture, are pretty bad in the main. There are a few standouts in each era. The standouts should be revered, but most of the daily efforts belong where they wind up, in the landfill. The state of the nation? Steady on. The Founders signed up for better or for worse. Enjoy the best, ignore the worst, keep an eye on the mediocre, because you just never can tell.