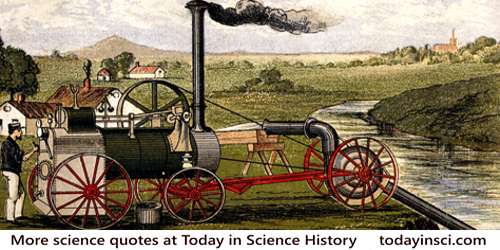

Steam trains unleash memories in a vanishing tribe of rail witnesses, as does the scent of tomato leaves for children of gardeners. A lonesome whistle or chuffing engine can sidetrack a steam votary's thoughts with the urgency of eternal truth. Click the sound button, below, to see if you're one of them.

Admittedly, there is a touch of nostalgia in steam-train memories, and often nothing more. But for some the experience is grittier, and yet more sphinxlike. That high, solitary whine echoes the chords of the human mystery: to be alive, yet as insubstantial as dissipating steam.

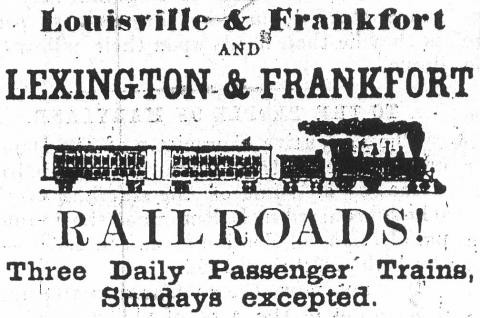

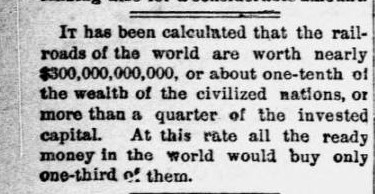

Trains were big business in past centuries, especially in America. See the nearby news clipping. They were the enabling business for all of commerce.

They are still big business, artfully so because their importance has receded in notoriety as more notorious enterprises have arisen. Trains have gone from comets to faint stars in American culture, and the steam train is the white dwarf, orbiting well beyond our home galaxy.

Automobiles will be the next transformative machine to roll into a museum exhibit. They have already begun their long, one-way slide off the hill of every day. Someday, nothing of cars will be remembered except their shapes, steering wheels and horns.

As has happened with steam engines, auto operation and its dangers will be lost in history's summary. Our future selves might reel at the thought of 2500 gallons of flammable liquid hurtling down the road, just as we are horrified to learn of steam explosions and bone-popping control levers. Will future folk strive to know us by grabbing a gearshift?

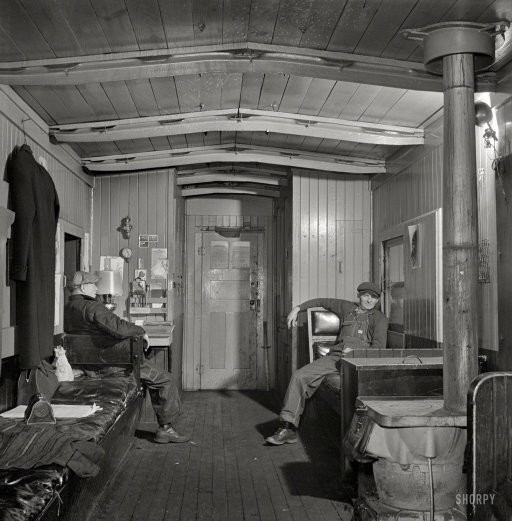

What did it feel like to be one of those early railroad workers, navigating the threats of their particular period of sic transit gloria mundi? That itch to explore the old steam culture is an attempt to return to a past human experience, to know those disappeared ones by imitating their actions.

Steam trains were behemoths, grand machines, theory adapted to reality through estimations, workarounds, and the bespoke jiggering of knobs and levers. The engineer operated an Olympian assembly of cast iron, tubes, wheels and gears. It was equivalent to about 3000 horses, give or take. Railroaders have often disdained engine ratings. The equations and their myriad uncontrolled variables can overwhelm, and those who don't understand them are loath to admit it, an impulse we share with those old railroaders.

Someone standing on the footplate (railroader lingo for the floor of the engine cab), when railroading was young, thinking about the beastly locomotive's 3000 horsepower must have been exhilarated and dazzled. The concept, in those days, would have conjured a literal image of 3000 horses, the critters that powered civilization.

Horses were everywhere, in twos and fours and more. But three-thousand-horse teams caressed the infinite. Implied was some giant harness, complex hitching mechanism, and fantastic feeding scheme. Think of all those reins. And manure. Yet, here was a 3000 horsepower locomotive.

Danger was paramount with steam locomotives. Boilers exploded. Trains collided. Mark Twain's brother had been blown up. Nineteenth century railroaders lived with locomotive accidents, and their numerous lame, dismembered compatriots were constant reminders.

Those ancient, disinterested machines had enormous lethality. And still, human beings, like ourselves, routinely jumped onto them, and drove them all around the country. We long to know those folk by understanding what they actually did. A century of context separates us, but we can almost replicate their actions. We can almost touch their experience.

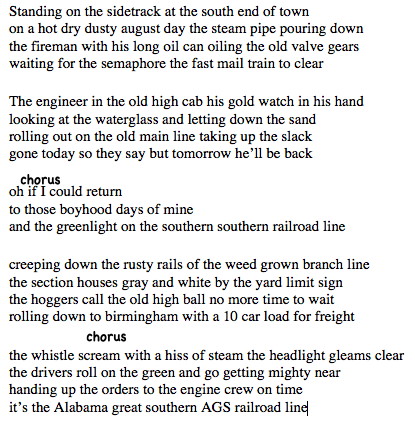

A good place to start is that song at the top by Tony Rice, "Greenlight on the Southern" (lyrics at left). Almost every line has a nugget of train lore. The first reminds us the railroad yards were on the "south end" of town, that is, the low-rent district.

"Steam pipe pouring down," probably refers to the "blow-down" performed to clear accumulating scale from the boiler, and sometimes to chase the spectators away.

We see the fireman walking through his pre-trip checklist with a long-necked oilcan. We learn about the system of signals, called the semaphore, alerting train crews, in the pre-radio days, of "clear" tracks ahead.

In the next stanza the engineer consults his watch. Schedules kept trains from colliding. He checks the waterglass for the water level in the boiler, also a life-and-death matter. If the water didn't cover the crown head, where the boiler meets the firebox, the engine would explode.

Letting down the sand," refers to dropping sand on the track from the sand dome, to increase traction so the drive wheels wouldn't slip.

"Taking up the slack" was analogous to letting out the clutch on an automobile. There was just enough slack in the couplings for each car to lurch forward independently, with the engineer adjusting the throttle for the increasing weight without causing the wheels to slip. We even get a glimpse of the inner life of the train crew, rolling from the sidetrack onto the dangerous mainline, with the full expectation of coming back soon.

The chorus is the singer explaining himself. His nostalgic lament emphasizes the lyricism of the rest of the song, and the hope it might channel him into the souls of those long-gone train crews.

The next stanza surveys the train yard, section houses where the workers lived, the less-used side rails, and the border between railroading and town. An engineer was called a hogger, perhaps because the locomotives had once been called hogs. Calling the highball was the engineer's signal to the crew that they were cleared to proceed. We even get the length of the train, short by modern standards.

In the last stanza we get to the whistle and the headlight, modern idols of the steam era. Green lanterns meant go, orders were handed up to the engineer in the cab, and at the end we get a plug for someone's favorite railroad company. Pretty good history lesson with a pleasant melody.

Close Window

For a better understanding of the art of driving a steam locomotive, let's consult someone who actually did it. At left is an account posted to the website www dot trainorders dot com in 2002 by someone called MTMEngineer. (Note: You might have to click the top-left icon in the popup display to get a full image).

This is probably as close as we'll get to understanding what it feels like to drive a steam locomotive. Thanks, MTMEngineer, for that marvelous lesson. Still, we don't quite enter the experience of those 19th century trainmen, who lacked radios, coordinated air brakes, and other modern conveniences, like plumbing.

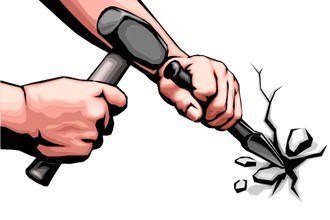

An important detail in the above description is the Johnson Bar. It's a long-forgotten relic of the steam days that never shows up in movies and books. In popular tellings there is a throttle, maybe some brakes, a little shoveling, and a whistle.

The Johnson Bar was a dangerous appliance, largely phased out and automated in modern steam applications. It controlled the piston-steam cycle, and is analogous to the spark-timing on a gasoline engine. It was a lever that locked into place at various "notches" to determine when steam was injected into the cylinder.

Pushing it forward maximized steam (power) for forward motion, centering it withheld steam, stopping the train, and pulling it back reversed the direction of the stroke. It is sometimes referred to as the reverse lever since it was used to back the train. It was set to different positions depending on the stage of acceleration or deceleration, and its setting determined the power and efficiency of the engine.

Railroad companies specified the desired cruising position of the Johnson Bar to maximize efficiency, and this was commonly called the "company notch." Why it was called the Johnson Bar is disputed, and we've found no authoritative account.

Much is written about trouble with the Johnson Bar. Since it connected directly to the engine stroke, it was under tremendous pressure during operation. Releasing it to change notches required caution, skill, and strength. Broken bones made it as notorious as the crank on a model T.

Close Window

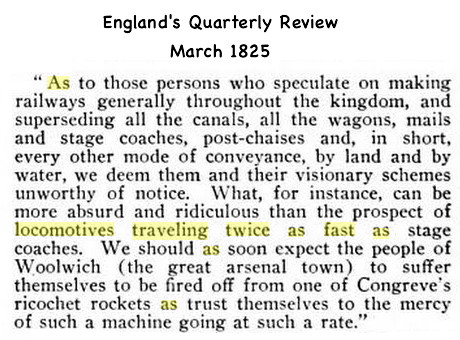

By the way, let's not forget steam trains were once the world's controversial technology, even more disruptive, and just as vehemently ridiculed, as today's electronic jeejaws. It's been almost 200 years since England's Quarterly Review tried bulwarking against their hell-bent approach (see left).

Trains have inspired some excellent songs, and we've included a few here. For full effect, turn on the train sounds while listening to the songs. Besides the wonderful "Greenlight on the Southern," be sure to listen to Doc Watson on "Greenville Trestle." Unlike Tony Rice, he doesn't show us the train operation, but reminds us why old men try so hard to bring back their train memories.

We also have two versions of "Waiting for a Train," Jimmy Rodgers' tuneful hobo lament. Hobos figure prominently in train songs, including Tom Paxton's defiant "Ramblin' Boy" (reprised behind the epigraph below, in its 1964 form), and Arlo Guthrie's "Hobo's Lullaby." The others, by Joan Baez, Leadbelly, and a return of Tony Rice and Arlo, tell us about the experience of seeing a train, or, with Arlo, being a train. And, don't miss the soaring voice of Mary McCaslin mourning her lost love in the memory of a great train.

There is a literature of trains, but it is pretty skimpy and unfulfilling. It doesn't tell us much about what actually happened in the cab, or in the caboose, or at the brake controls.

We've found some poetry, but, like many subjects of routine human experience, it has produced little of what we might call "major" poetry, except for Emily Dickinson (and "Something Special" below). There is some, though, along with an early opinion on the value of a specific train poem.

In 1857 the scholarly view was that trains weren't really the stuff of great art. That's still the scholarly view, and maybe the reality, but they sure are the stuff of being human, which is an art in itself.

At the bottom you'll find a few videos about driving steam trains.

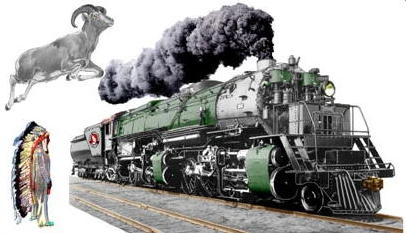

"Switching Cars in Zanesville" was written by Herbert R. Tipton and set to music and sung by Cliff Jinks. You can read more about that at this link, and you can watch Cliff perform the song in the bottom video below.

An Assortment of Videos on Steam Engine Operation (followed by a not-to-be-missed epigraph)

Carls Sandburg's Lyrics from the American Songbag

Those Gambler's Blues

(now known as St. James Infirmary)

Lyrics from "The American Songbag"

by Carl Sandburg (1927)

----------------------------------

Harwood Blog

It was down in old Joe's bar-room,

On a corner by the square,

The drinks were served as usual,

And a goodly crowd was there.

On my left stood Joe McKenny,

His eyes bloodshot and red,

He gazed at the crowd around him,

And these are the words he said:

"As I passed by the old infirmary,

I saw my sweetheart there,

All stretched on a table,

So pale, so cold, so fair.

Sixteen coal-black horses,

All hitched to a rubber-tired hack,

Carried seven girls to the graveyard,

And only six of 'em comin' back.

Oh, when I die, just bury me,

In a box-back coat and hat,

Put a twenty dollar gold piece

on my watch chain,

To let the Lord know I'm standin' pat.

Six crap shooters as pall bearers,

Let a chorus girl sing me a song,

With a jazz band on my hearse,

To raise hell as we go along."

And now you've heard my story,

I'll take another shot of booze,

If anybody happens to ask you,

Then I've got those gambler's blues.

Who in the world cares about Steam Trains?