“You never knew your Uncle Eldy,” was among the bedrock truths of infancy, including sitting in the dark with drawn shades, an Iwo Jima war bond ad in the post office, flashlight beams knifing through the night sky, and two telephone calls that collapsed my mother in grief.

The mystery of the blackouts reconciled gradually, after we’d moved from the San Francisco area, as did those searching flashlights in the sky, celebrating the “all clear,” after the blackouts were lifted.

My mother’s two anguished phone calls remained mysteries for six decades until I learned about two ancient War Department communications to my grandparents, one when Uncle Eldy was shot down, in March, 1945, and the other when his body was recovered in June. The tumblers dropped in a secret lock. Those two distressing phone calls, carved into my memory like old intials on a desktop, informed my mother of Eldy's disappearance when I was 27 months old, and of his death at 31 months. The family trauma was deep and lasting.

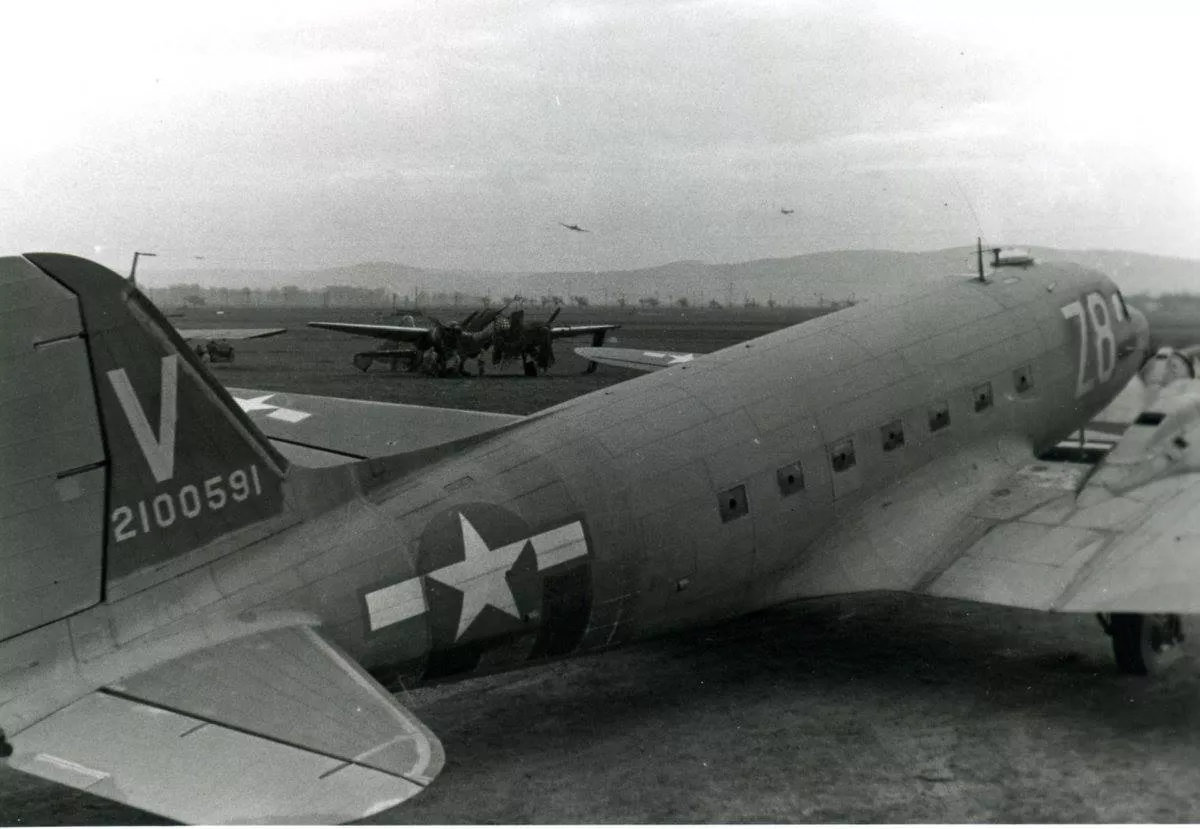

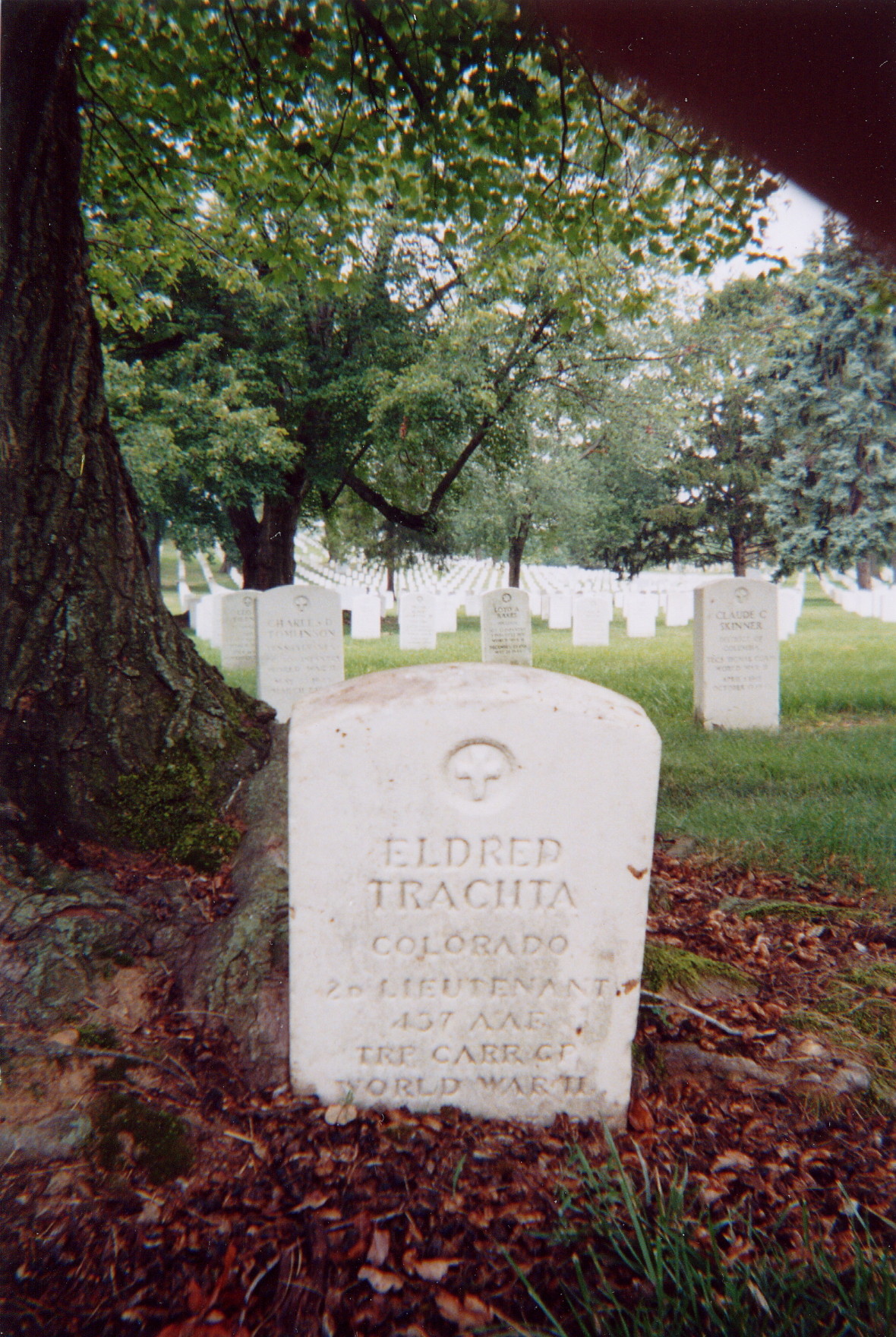

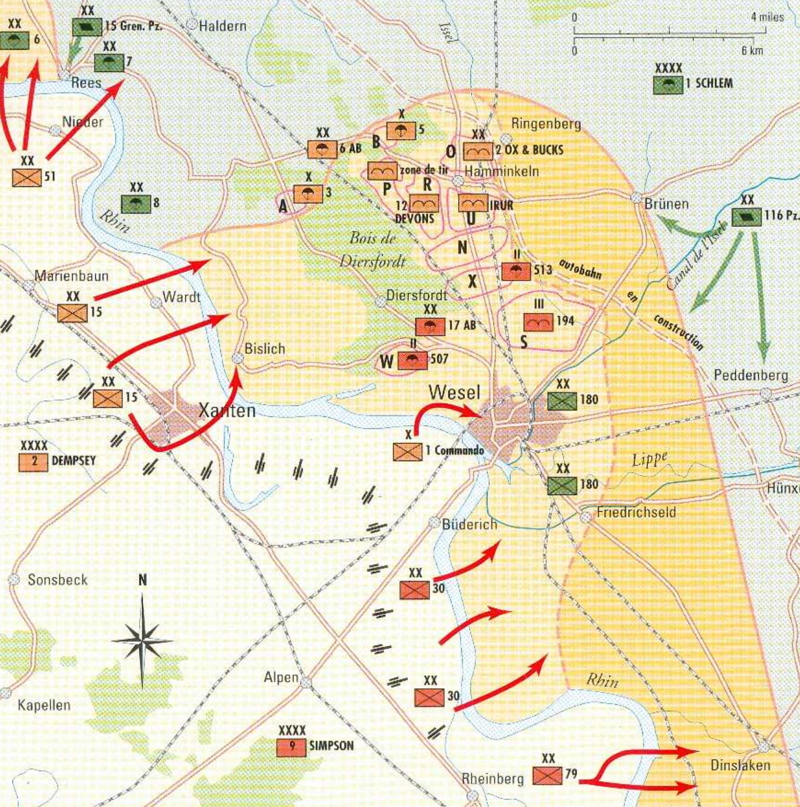

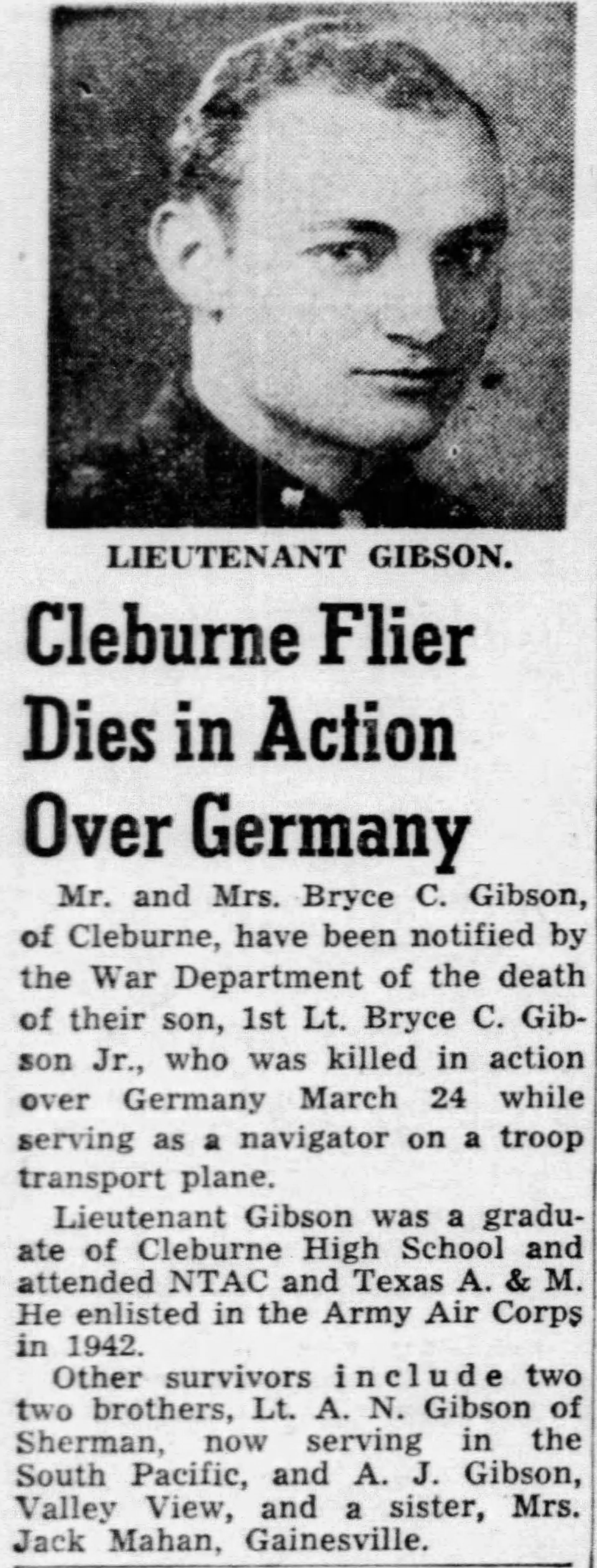

Eldred “Eldy” Trachta was the co-pilot of a C-47 (SKYtrain) transport plane (number 43-15493), departing Maisoncelles, France towing two gliders to Wesel, Germany as part of Operation Varsity, March 24, 1945. During the mission, at about 10:30 AM, northeast of the target, his transport took antiaircraft fire and burst into flames, disappearing from view near Wessel Germany. In August 1949 he was buried in Arlington Cemetery. His father attended the ceremony and met a member of the crew who had managed to escape. He said the right wing was hit by anti-aircraft fire.

Eldy was the third of four children, my aunt being the youngest. He was two years younger than my father, and they were exceptionally close. He was seldom mentioned in my lifetime, and then in quiet tones. Sorrow shrouded the memories of those who’d known him, and forestalled mentions by everyone else. My father mourned his little brother all his life.

Just before my father’s death he bought a new computer. “What’s your password?” I asked. “Eldy,” he whispered.

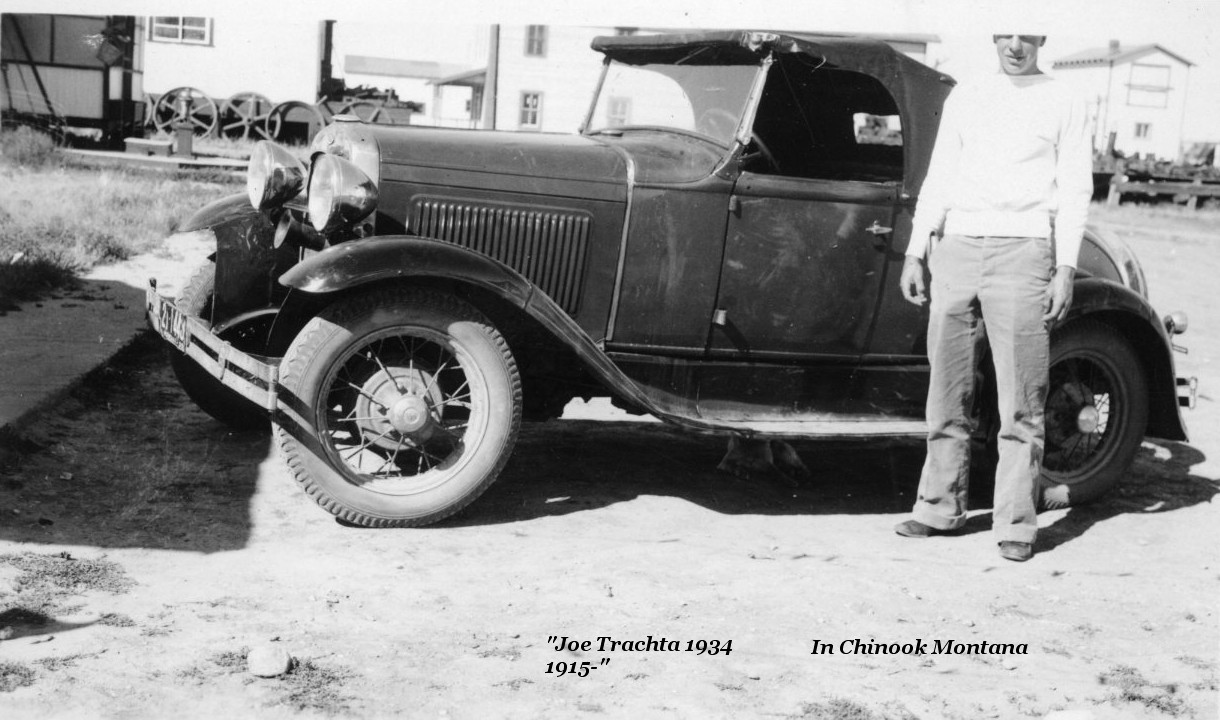

Eldy was born in Meeker, Colorado in 1917. His father was a wildcatter, whose children had many addresses. They lived in Yellowstone Park one summer, and saw Calvin Coolidge tour through. Eldy graduaed high school in 1936 from Oilmont Montana, and attended college in Missoula, Montana , working summers in the oil fields as a pumper. In December, 1941, his older brother, Stanley, commanding the Marine detachment on board the West Virginia, survived Pearl Harbor while Eldy was still in college. He was scheduled to start his last quater in the summer of 1941. He got a job in the oil fields and apparently never finished. He enlisted in March 1943.

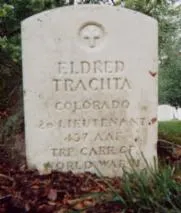

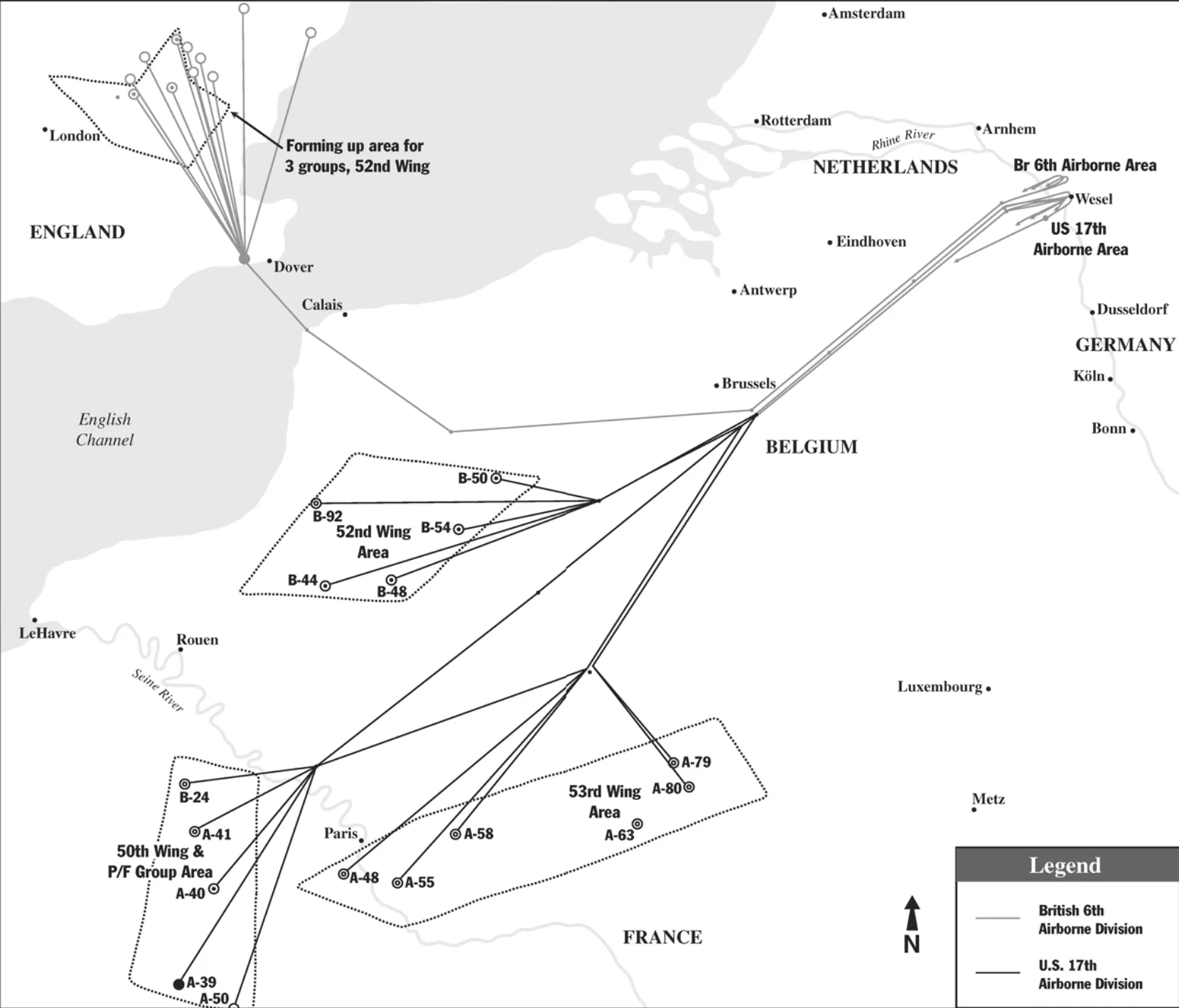

He was selected for pilot training, joined the Army Air Corp, trained on the C-47 Skytrain, and shipped out to Ramsbury England attached to the 84th Squadron of the 437th Troop Carrier Group of the 9th USAAF. They were dispatched to field A58 in Coulommiers, France, where Eldy became co-pilot to Captain Vic Deer on C-47 Skytrain number 43-15493. There on 24 March, they became part of Operation Varsity the last planned combat mission for the men of the 437th and the last Allied airborne operation of WW2. He was shot down over Wesel, Germany. In 1949 his body was returned to America for internment in Arlington National Cemetery. In 1953 his alma mater, Montana State University in Missoula, dedicated its new Carillon to former students who fell in WW II. Eldy is named on a plaque donated by the class of 1953.

Recently, after everyone who knew him was gone, we discovered two long-dormant stories about my Uncle Eldy. One, a narration of his last moments, and the other about the consequences of his unlived life.

My brother corresponded with a radio operator who flew the Operation Varsity mission in another squadron. He directed my brother to Neil Stevens, another veteran of the mission, who alerted us to a book about the 437th Troop Carrier Group, written by one of its members, Frank Guild. From it we learned of an eyewitness account of Uncle Eldy’s last minutes as recounted by the sole survivor of the flight.

You can read the details we’ve discovered in a popup nearby, but briefly, all crewmen except the pilot, Victor Deer, co-pilot Eldy, and Crew Chief T/Sgt Paul B (Brack) Lefevere, were incapacitated by the anti-aircraft fire. Deer elected to land the crippled craft, Eldy decided to help, and Lefevere jumped at about 700 feet. He saw the wing explode, and the plane disappear below the trees.

Eldy was confirmed dead in June, and his body interred in the Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial in Margraten-Aachen, Holland. In 1949 he was returned for burial in Arlington National Cemetery. His father attended the burial and talked to Sgt Lefever, who described the crash. This and other details are further discussed in a nearby popup.

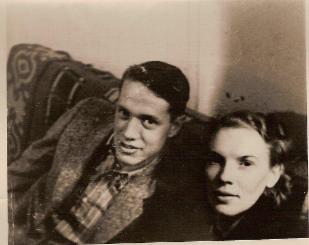

My father’s scribbled annotation on an old snapshot led to the discovery of a Eldy’s girlfriend, who’d mourned him all her adult life. From her niece we learned she’d never married. Eldy was mentioned in her obituary.

Like all young people, Eldy was building a life before the war, and fully expected to get on with it afterward. Peace doesn’t heal the wounds of war. Life grows a different way, and most of us, most of the time, are unaware of the branches that didn’t mature. Based solely on pictures my parents kept, and a few guarded comments, I found the missing branch of Eldy’s life. She was Elizabeth Evelyn (Betty) Winborne of Parco, Wyoming, and a reference to the settlement of her estate prompted me to send the following query to, I assumed, her attorney.

"I am doing genealogy research on my uncle, Eldred Trachta, of Carbon County, Wyoming, who was KIA in WW II. I have pictures of his girlfriend, Betty Winborne, whom I have identified as Elizabeth Evelyn Winborne. I’ve seen public records indicating you handled Ms Winborne’s estate when she passed away in 2005. Can you give me any information about her, or names of relatives I might be able to contact?"

My letter actually went to Betty’s niece, Nannette Slingerland, and she graciously responded as follows.

"… Yes, my aunt was very much in love with your Uncle and over the years she often spoke of “Eldy”. They had planned to marry but decided that they both needed to finish their schooling first. A decision she regretted throughout her life.

"… Betty was going to the University of Wyoming and I think that is where they met, but…I am not totally sure. I never felt comfortable asking personal questions, because it was always obvious to me that there was a sad, broken heart not too far under the surface on the subject of “Eldy”. … Occasionally, Betty’s mother, my grandmother, would refer to Betty’s loss. She concurred on what a fine young man Eldy was.

"I recall Betty mentioning how tall and handsome he was, an athlete…basketball, I think? She also spoke of Eldy having a keen, compassionate mind, practiced what he preached, fair minded, great sense of humor and did not tolerate fools or any underhanded behavior in those with whom he associated. The war interrupted Eldy’s schooling and changed everything. Your Uncle eagerly volunteered after Pearl Harbor and was one of the first killed from Wyoming….

"…My Aunt was also quite athletic and shared that interest among others with Eldy. Betty was obtaining a degree in physical education, and she added primary education so that she would have multiple skills for success in her desire to become a teacher. Betty was in school from the time she was 5 until she retired at the age of 62. Much of her teaching career was with the Fort Washakie School District, run by the Wind River Inter-Tribal Council. There is still an academic award at the school named for Betty. over the years, there were occasions that Betty sparked serious interest in a few choice men, however, nothing ever came of those brief encounters, with Betty commenting that they did not come close to being the man that your Uncle was so she never married.

"Not fulfilling her dream of a life with Eldy was a fact she regretted and to her dying day regretted not having children of her own. Her sister, Margaret, my mother, only had me and they also lost their only brother, Kenneth Winborne before he had any children which was about five years or so after the loss of Eldy. So our Winborne family name lineage ended with Betty’s death in 2005….”

Interestingly, Betty’s younger brother, Kenneth, became a cold-war casualty in 1948. During the Berlin Air Lift crisis, at a time when the Soviet Union was secretly preparing to test its first atomic bomb in Siberia, the Air Force Secretary, Stuart Symington, was demanding pictures of Soviet airfields. Locals in Alaska were telling stories about overflights by Soviet aircraft, and crash landings of U. S. aircraft with bullet holes in them. Lt. Winborne was piloting a surveillance P-51H when he disappeared without a trace. One assumes he was lost on an intelligence-gathering mission.

...............

You could send us your comments by email