Send a Message

There's More

You may have wondered how people traveled across the great western part of the United States in the days before roads.

How in the world did someone drive a wagon across the wilderness? What routes did they take? Why did they pick those routes? How are current roads influenced by those early choices? When did the trails become roads?

My great-great-grandfather, Thomas Hart Benton Stasey, traveled across the plains from Hannibal, Missouri to Sacramento California, in 1854, seeking his fortune in gold. He returned to Missouri in 1859. He wrote letters from California, but made few comments on the trip itself, mentioning only the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and Fort Laramie. The route he followed has come to be called the California Road, coinciding with the Oregon Road, the Platte River Road, and the Mormon Road for vast stretches. Seventy years later, his grandson followed much the same route to Nebraska, and then Wyoming, and finally, California, pursuing a livelihood, if not a fortune. He too returned to northern Missouri, following much the same route as his grandfather.

The Platte River Road

The continental United States is vast, and today many roads cross it, east and west, as well as north and south. Curiosity about the route my grandfather and his grandfather followed in their round trips out of Missouri devolves into two questions: where was it, and why was it there, as opposed to any other line across the continent?

The first question can be answered with a little study, because it has been heavily documented. Numerous contemporary accounts exist, including the nineteenth century equivalent of tour guides, diaries, and news accounts.

The question occupies several books, but two are definitive. Merrill J. Mattes published “The Great Platte River Road,” in 1969, and John D. Unruh, Jr., published “The Plains Across,” in 1976. These two books, in addition to their compact presentation of information and their extensive analyses, feature bibliographies covering all useful, historical publications on the subject, and essential primary sources such as diaries, memoirs and periodicals. Lately, in 2015, a popular book about retracing the route, “The Oregon Trail,” by Rinker Buck, is interesting reading, and traces a close approximation to the old route, using modern roads. Many of Dr. Mattes' source materials are available online, including for example, those held by the Oregon-California Trails Association.

Where was the old route, and why was it located where it was? Why did my grandfather follow much the same route, seventy years later, and again ninety years later, when he returned to Missouri? These are the questions that occupy us here.

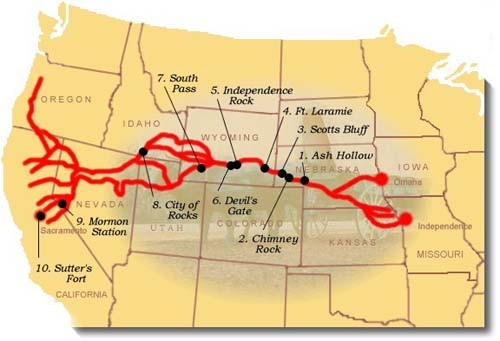

The Oregon and California roads derive from trails blazed by trappers and explorers in the early nineteenth century. They probably have their origin in game trails. Traveling west out of the United States and across the plains became a significant enterprise in the 1840s, with the massive, for the time, emigration to Oregon. At first the emigrants left from Independence, Missouri, because that was the point from which the already existing Santa Fe Trail departed, and it was known to be a place for outfitting trips across the plains. From there the emigrants went northwest to the Platte River, which they followed westward to the continental divide, before tending northward into Oregon. A few emigrants were already going to California, as my great-great-grandfather did in the mid 1850s, and they left the Oregon Trail in what is now western Wyoming, cutting south into present-day Utah, and west across the Sierra Nevada Mountains into California.

As emigration increased, owing to both the lure of farm land in Oregon, and the popular agitation to populate the Oregon Territory in the name of Manifest Destiny, a powerful political impulse of the time, jumping off places further north, closer to the Platte River, became popular. St. Joseph Missouri became the most popular embarkation point for the Platte River Road, for both Oregon and California emigrants, in the mid to late 1840s. It eventually shared that honor with Council Bluffs Iowa. Council Bluffs was used mainly by the Mormon migration at first but came later into general use. Those leaving from Independence and St. Joseph generally traveled west on the south side of the Platte River, while those leaving from Council Bluffs normally traveled the north side. Additionally, there were numerous other small enterprises between Independence and Council Bluffs, where entrepreneurs operated ferries, taking emigrants across the Missouri River.

Don't Go West, Young Man

As emigration increased, owing to both the lure of farm land in Oregon, and the popular agitation to populate the Oregon Territory in the name of Manifest Destiny, a powerful political impulse of the time, jumping off places further north, closer to the Platte River, became popular. St. Joseph Missouri became the most popular embarkation point for the Platte River Road, for both Oregon and California emigrants, in the mid to late 1840s. It eventually shared that honor with Council Bluffs Iowa. Council Bluffs was used mainly by the Mormon migration at first but came later into general use. Those leaving from Independence and St. Joseph generally traveled west on the south side of the Platte River, while those leaving from Council Bluffs normally traveled the north side. Additionally, there were numerous other small enterprises between Independence and Council Bluffs, where entrepreneurs operated ferries, taking emigrants across the Missouri River.

What caused the road to be where it was? In the nineteenth century, and particularly in 1840, there were two major problems in getting across the plains. First, there were the Rocky Mountains. It was universally believed, in the early 1840s, that the Rocky Mountains posed an insurmountable obstacle for travelers from the eastern states of the United States, bound for its territories on the Pacific Coast. That belief was central to the foreign policy of the United Kingdom, and the dispute over the Oregon Territory. The English believed themselves certain to prevail, since it was impossible for the United States to either populate or defend such a remote region. In America, no less a person than Horace Greeley advised adamantly against anyone attempting a trip to Oregon. He forecast certain death for those who tried. It was considered impossible to get wagons up and down the steep inclines of those formidable mountains.

The second problem in crossing the plains was to find a route with sufficient water for the livestock, necessary for transport. Oxen, horses and mules were needed to pull the wagons and they needed water to drink, and to grow the pasture they would need for fuel.

The first of these problems had already been solved by 1840, but the solution was not yet in the popular mind. South Pass, in what is now western Wyoming, was first noticed by white men in 1812. It was rediscovered in 1823. In 1832, Captain Benjamin Bonneville was the first to cross the pass with wagons. Still, communication at the time was such that not until 1842 or 1843, when a substantial number of Oregon emigrants had crossed the plain and written letters home, did the existence of South Pass enter into the popular wisdom. Even Horace Greeley admitted it was possible to get across the mountains, but he still advised against it.

Beyond the divide, emigrants found two networks of rivers, one toward Oregon and another going south to California, that completed the solution to the second problem and further defined the course of the two roads.

South Pass is the lowest point on the Continental Divide between the Central and Southern Rockies. It is a low, broad region over which all of the memoirists and diarists exclaimed, comparing the easy passage to a drive across a meadow. South Pass has another feature that ensured the road of emigration would anchor itself there. It is at the headwaters of the Sweetwater River, itself a tributary of the Platte River, which empties into the Missouri. Thus, heading for South Pass solved the second problem of water, at least to the continental divide.

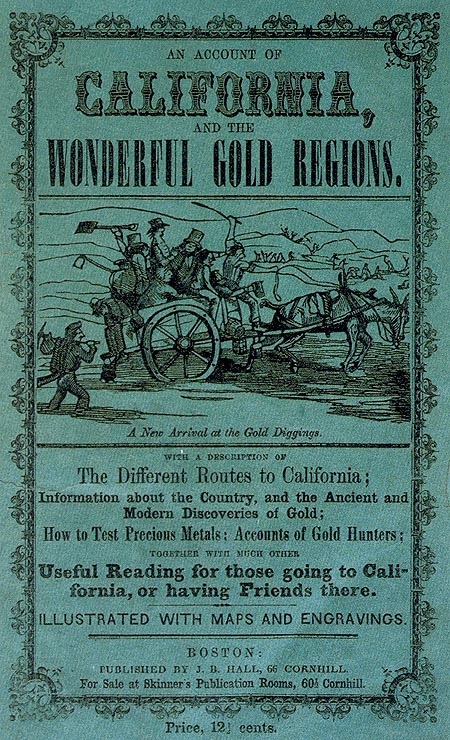

These days we can pull out our telephones and find a normally reliable route to just about anywhere. In the nineteenth century people relied mostly on rumors, and the wisdom of people who claimed to have been there. Here is a tour guide published in 1845. You'll notice, in Chapter 14, it references, in all solemnity, the mythical "Brown's and Hooker's peaks," which appeared in studious accounts of the west, right into the twentieth century.

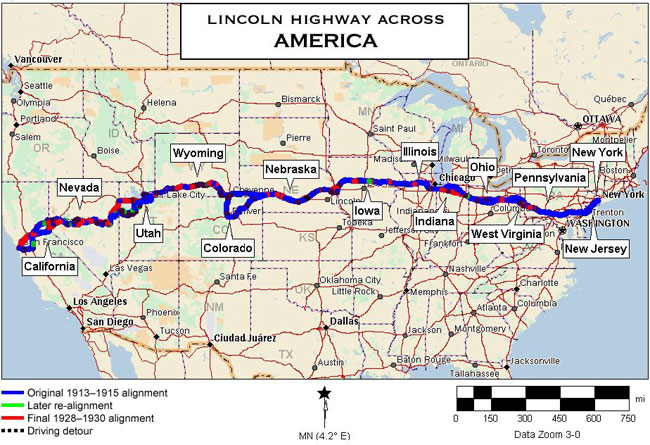

The transcontinental railroad followed much the same route as the California Road, once it got to Nebraska, for much the same reasons. It jumped off from Omaha, instead of St. Joseph Missouri, but by that time, 1869, there were railroads up and down the Missouri River, and crossing the state of Missouri, along the routes the wagon trains had taken. In 1912 the Lincoln Memorial Highway was commissioned to cross the continent from New York to San Francisco, and it trailed close to the old California Road, for at least one of the same reasons. South Pass was still the easiest way across the Rocky Mountains, and, by that time, the original emigration route touched the most prosperous and well established areas in the western states.

By 1912, motoring around the country had gotten to be almost popular. A jaunty trio of young men from Texas set off for San Francisco in 1912. Their adventures are recounted in a newspaper article of the time (or read the article here).

They set out from Weatherford, Texas on a winding 6,500 mile road trip to San Francisco and back in a Stoddard-Dayton Saybrook 48 horsepower car. Despite encountering many mishaps along the way, including poor and non-existent roads, mechanical malfunctions, and having to be pulled by a team of horses through 30 miles of sand to Yuma, Arizona, the three completed the adventure with quite a story to tell. Pictured below are the three travelers, Sam White and Barney Holland of Weatherford and Lem Scarbrough of Austin, standing next to the car owned by White that was taken on the trip. The women pictured and location are unknown. From the Bowie/Holland Collection.

Ike's Big Road Trip

The Lincoln Highway got an early test from the Army. In the 1840s, recall, it was widely assumed military strength could not be projected across the continent from the well-established eastern United States to the west coast. This assumption played heavily into foreign and domestic policy. While the problem was somewhat solved by rail, and sea power, and by the Panama Canal, it wasn’t until 1919 that the U.S. military tried moving large convoys over the nation’s road system.

At the end of WWI, the U.S. Army Motor Transport Corps sent 81 motorized vehicles from Washington D.C. to San Francisco. The expedition followed the Lincoln Highway, a somewhat notional road at that time, and is a subject of popular history because of the presence of brevet Lieutent Colonel Dwight Eisenhower, as a War Department observer.

Modern accounts of the trip are often couched in breathless irony about the ineptness of the whole undertaking, citing breakdowns and difficulties as if they were egregious examples of military, and Eisenhower incompetence. One writer, whose roadway experience apparently goes back no more than thirty years, accusingly notes the convoy arrived in San Francisco six days behind schedule! Traveling coast-to-coast over mud roads, and makeshift bridges in 1919, within a week of the schedule, was both excellent planning and remarkable execution.

Summing Up

When my great-great-grandfather headed west in 1854, the best guess is that he went down the old “Hound Dog Trail” from Hannibal to St. Joseph, and from there up the St. Joe Road to the Platte River, and from there across South Pass, and on to California. Coming back, he would have followed much the same route, with perhaps a few digressions where the road had been improved.

When his grandson, my grandfather, decided to leave Missouri to find work in the mid 1920s, the Hound Dog Trail had become a highway designated Route 8, now highway 36. It connected to the Lincoln Highway, the one and only artery across the continent. He followed relatives who had gone before him, and since they had settled in Wyoming and Nebraska, that’s what he did. Just prior to WW II, he went on to California, and, of course, he followed the best road, which was the Lincoln Highway, in a slow-motion echo of his grandfather’s trip, accompanied by my mother, the gold-seeker's great-granddaughter.

As it happened, my brother and I echoed the original trip again in 1946, when we accompanied our parents from California to northeastern Missouri, settling on a farm a few miles from where our great-great-grandfather had lived. We were not faithful to the old California Road, however, and went across the Rockies in Colorado, over roads that could not have been contemplated by our adventurous ancestor.

The other nineteenth century road across the continent, the southern route, was much less traveled during the gold rush, and for good reasons. It followed the old Santa Fe Trail from Independence, went south along the Rio Grande, following the Camino Real established by Mexico in very ancient times, and then snaked westward toward the Gila River. It followed a road blazed in 1846 by Colonel Cooke of the Mormon Battalion. It has been variously called Cooke’s Road, or Sonora Road, or the Gila Trail, or the Butterfield Stage Trail. It had the advantage of being open year round, unrestricted by snowfall, but it was much more barren and risky. Gold rushers following this route came mainly from the southern United States along the San Antonio-El Paso Road. During the gold rush, it was called the Southern Trail. It was gradually improved and shortened over the years, and in the 1880s it determined the route of the southern railroad. It is approximated by the Rio Grand River, and Interstate 10.

You can read an account of crossing to California via the southern route in the Journal of Reverend Benjamin Franklin Stevens of Hannibal. He set off with his son in April, 1849. The map below his picture approximates his route, based on place names in his journal and modern roads.

Who in the world cares about this stuff?