Fountain Clippings(click to see/hide)

Some maps(click to see/hide)

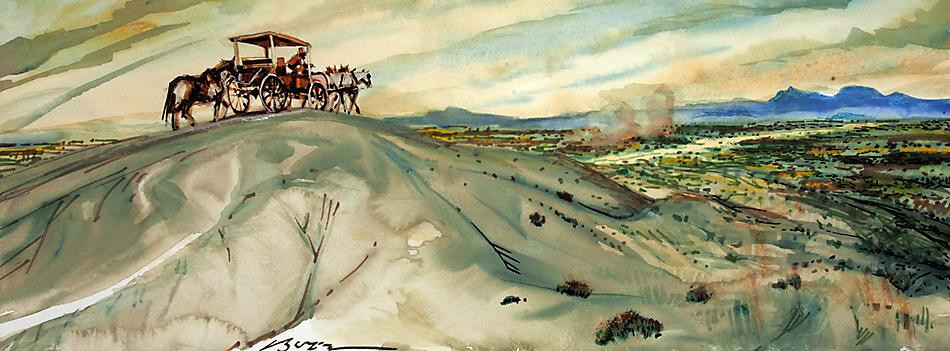

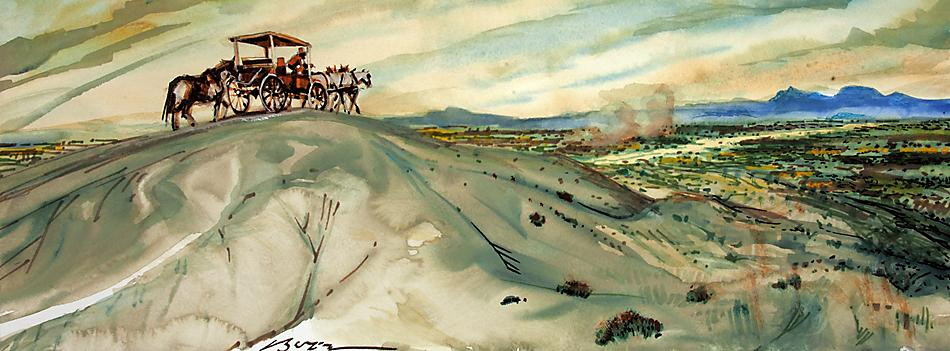

hen I moved to Alamogordo, New Mexico in the mid 1960s I met a local farmer named Herb Riffe. His acreage had been swallowed by the growing town, and by then adjoined my back yard. He and his new bride had arrived by horse and buggy from West Virginia in 1911. He still had the buggy and the bride, was still farming, and liked to talk. Most of what he said has faded to a montage of unrelated images. The only Herb Riffe story I remember started with, "There's a lot of mischief on those white sands." He told me about a man and his young son who'd disappeared on the old Mesilla-Alamogordo post road. "Disappeared without a trace," he said, and I thought he was telling a flying saucer tale. Later I heard of Colonel Albert J. Fountain and his son, Henry.

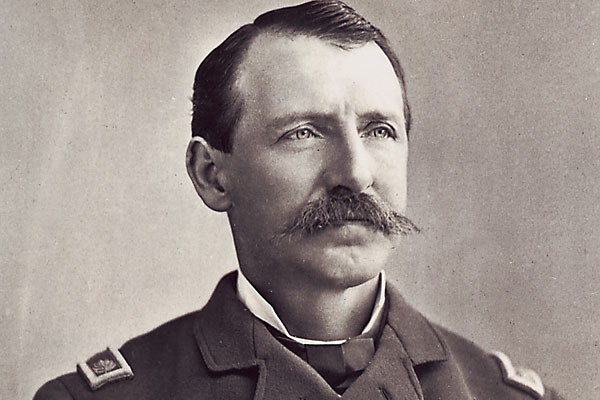

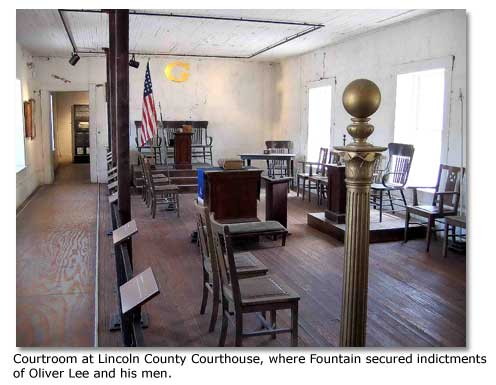

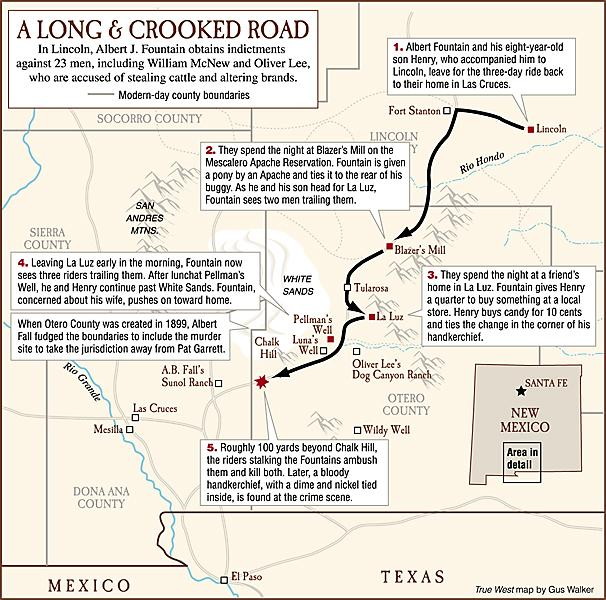

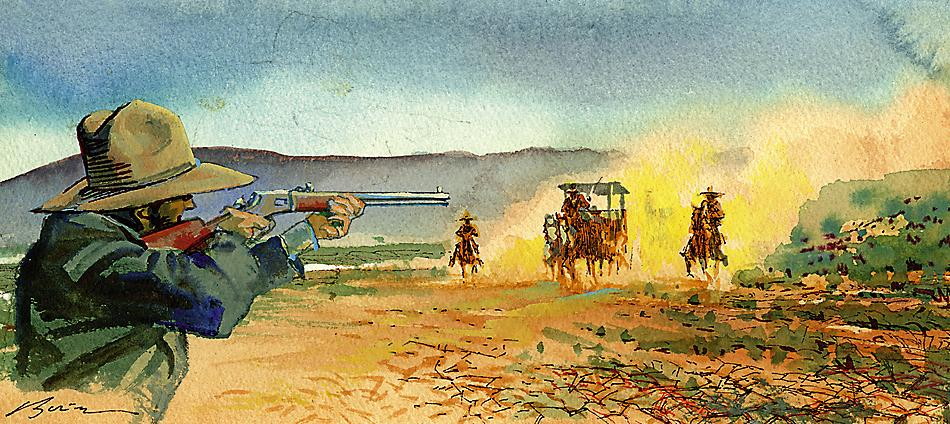

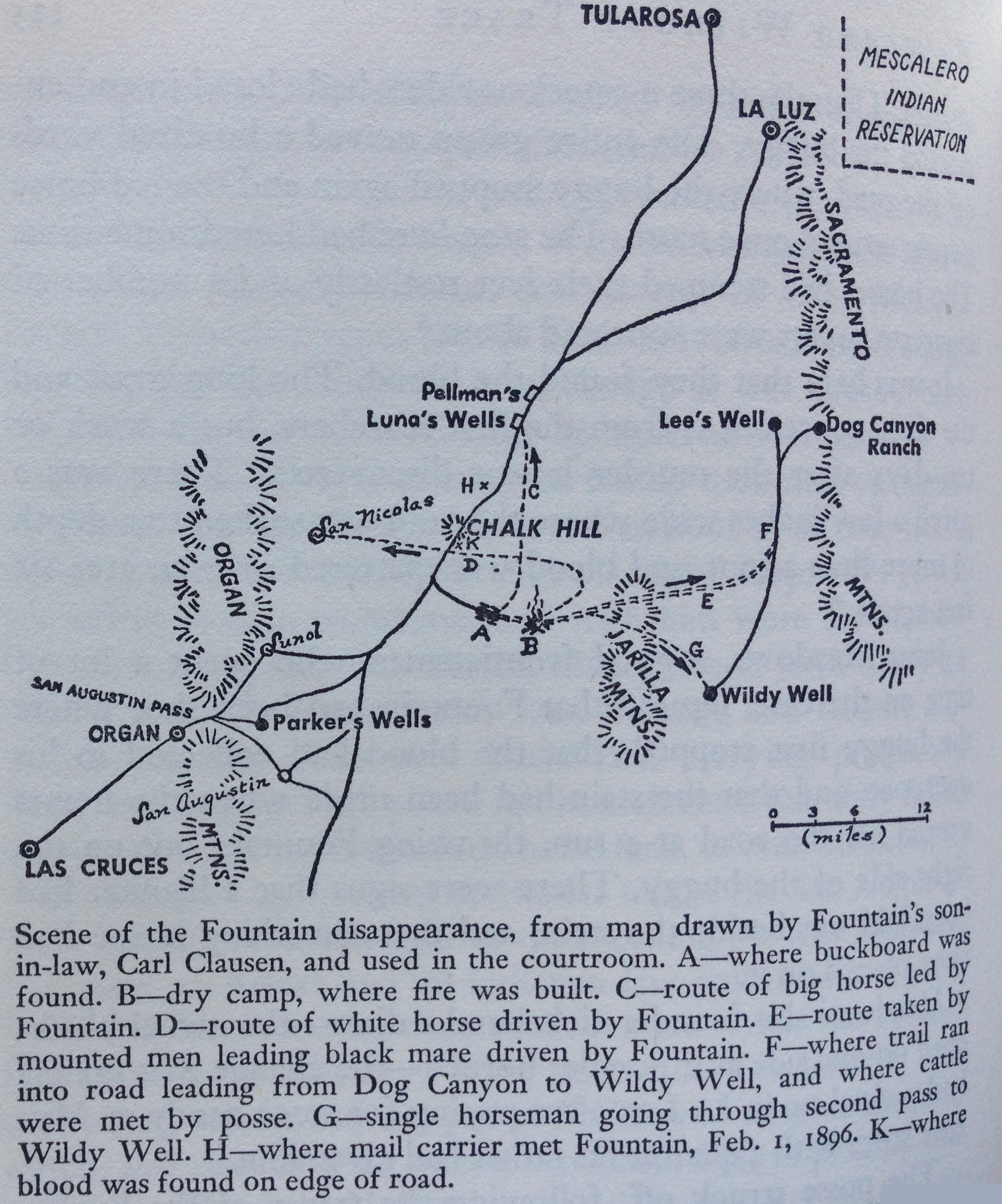

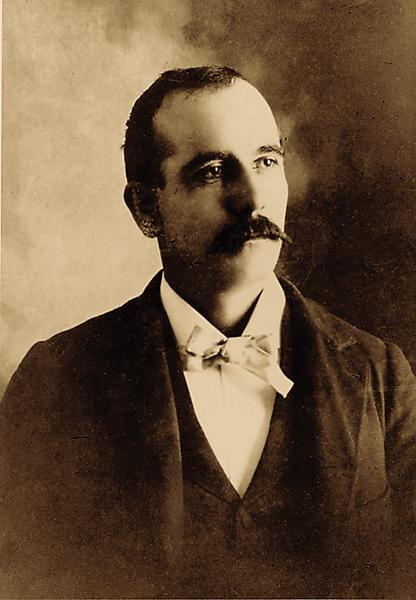

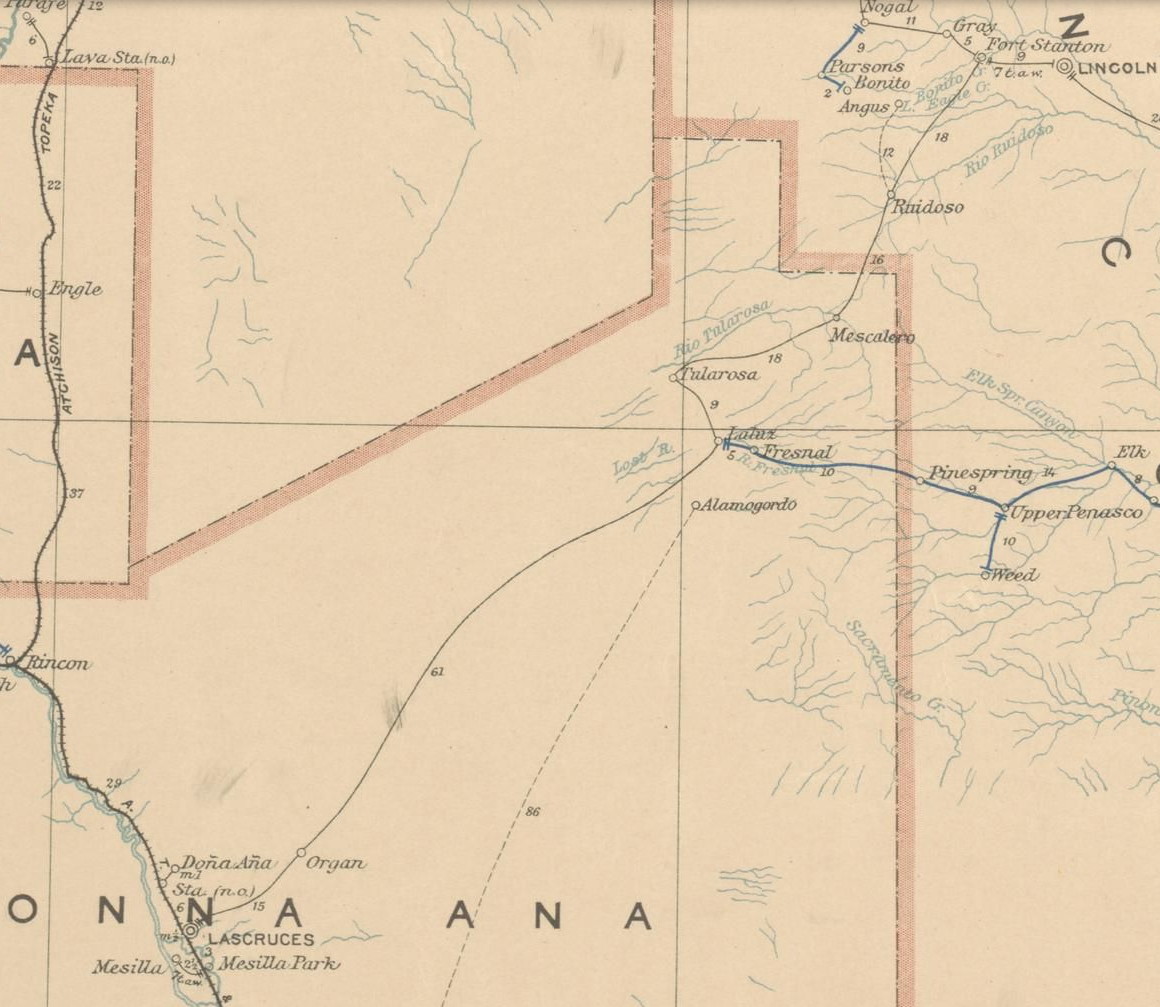

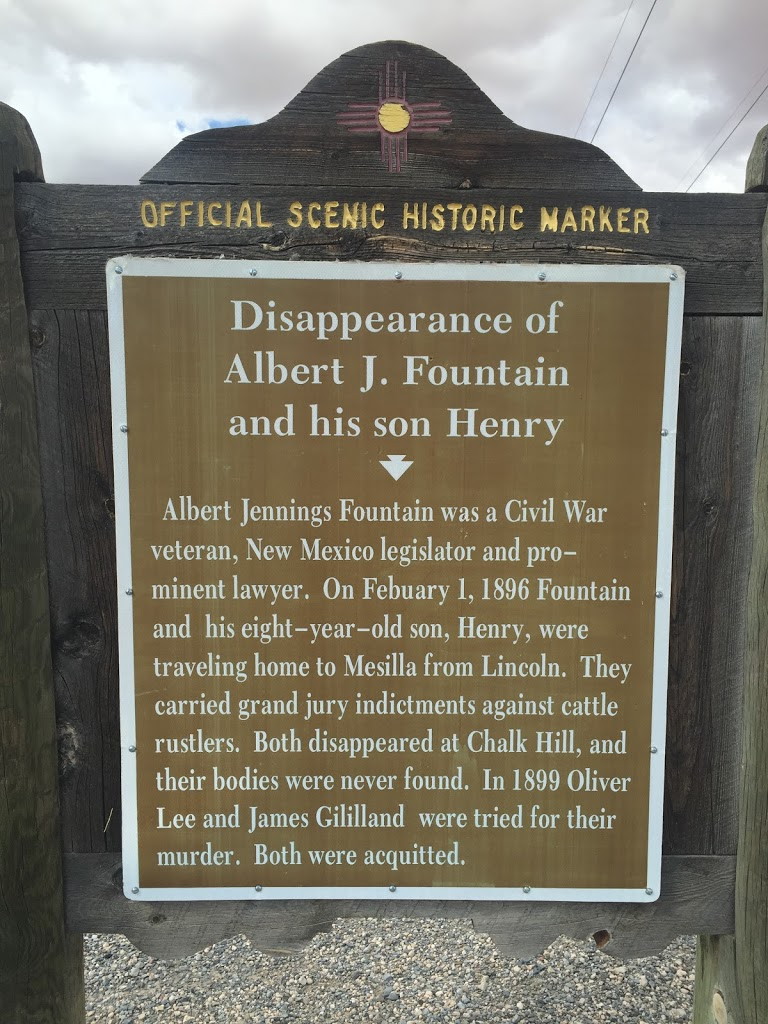

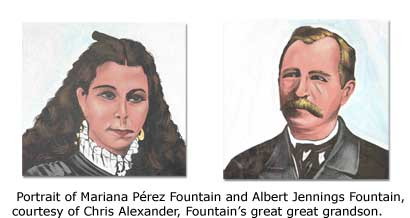

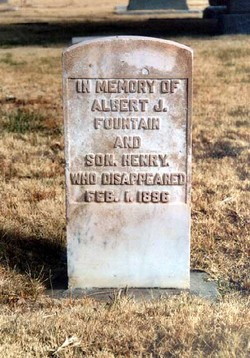

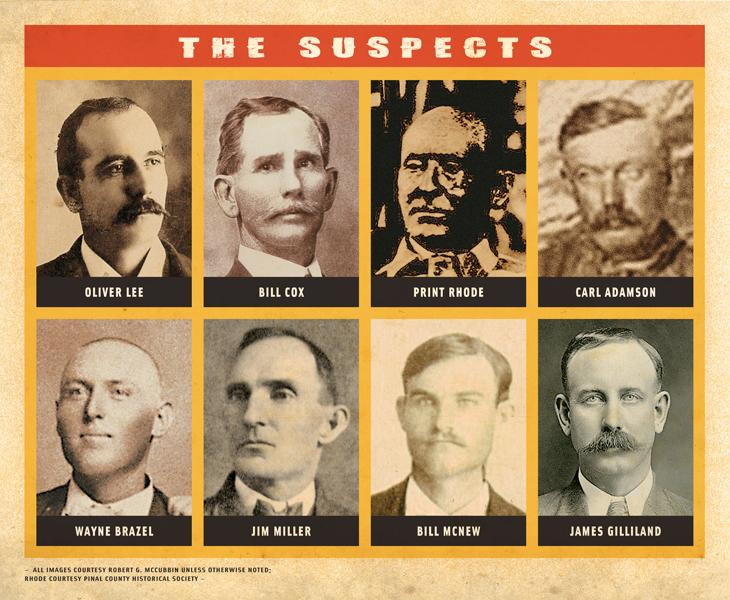

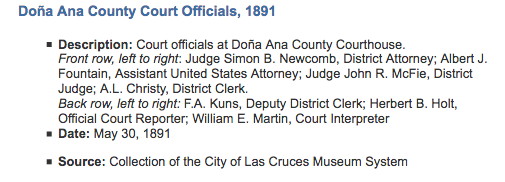

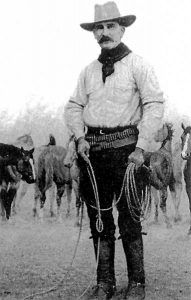

The story of Colonel Fountain's suspected murder still smolders in the Tularosa Basin. Touching it is like grabbing a skillet off the stove. You never know if it's going to be hot. The universally accepted facts are simple. Albert J. Fountain, at that time a lawyer from Mesilla, New Mexico, was employed by an association of local cattlemen to put a stop to the thieving of their assets. He'd gotten convictions against several people and indictments against others, including local rancher Oliver Lee, and some of his employees. On February 1, 1896, Fountain was driving his buckboard home to Mesilla from a court session in Lincoln, New Mexico, accompanied by his eight-year-old son, Henry. Several people saw him on the road during the day, but he didn't arrive home. His adult son, Albert Jr., alerted by a mail carrier who'd seen signs of trouble near the white sands, organized a search. They found wagon tracks leaving the main road at a prominent feature called Chalk Hill. The tracks led to the abandoned buckboard twelve miles south. A few personal effects were found, but most were missing, along with Fountain, his son and the horses. Blood was reported at Chalk Hill.

No one was convicted of murdering Albert J. Fountain and his adolescent son, but many people knew what happened, and many more have speculated. He and his killers still make headlines, over 100 years later, but the details get fuzzier as time passes. The rest of Fountain's family was pretty interesting too.

A 2013 dramatic production directed by Sean Pilcher, was based on Fountain's disappearance. For reasons undisclosed, it strays wildly from the historic facts, and tells a much less dramatic, more prosaic story than the truth. Shakespeare might have improved on history, but most of us cannot. Still, it's a western, so there's no confusion about the good guys and bad guys, and that makes it fun.

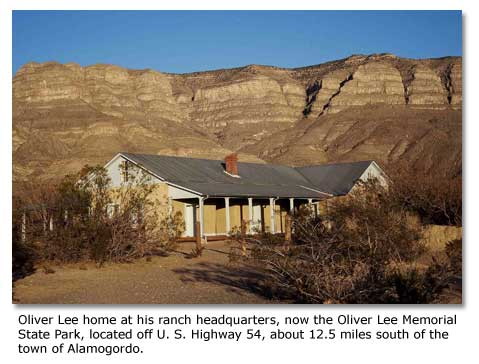

trail of horse tracks led from the buckboard to a campsite. From there three riders leading two horses were tracked in two directions. One horse went toward a line camp called Wildy Well, and the others toward a ranch site in Dog Canyon. Oliver Lee owned both. Lee and four of his employees were found at the Wildy Well camp, but they offered no information about Fountain's disappearance. The tracks heading toward Dog Canyon were obscured when two cowboys drove a herd of cattle across them. One of Fountain's horses was found at a post-road well. Albert, Henry, and the other two horses never appear in the public memory again

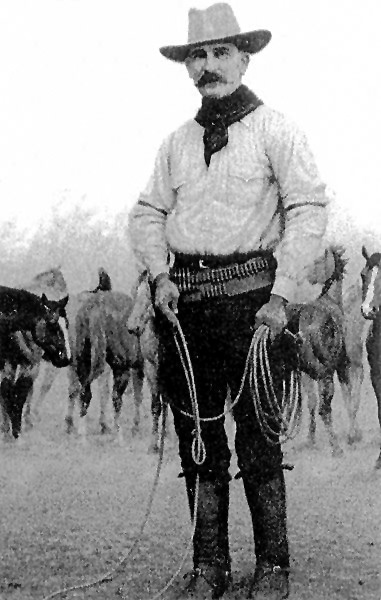

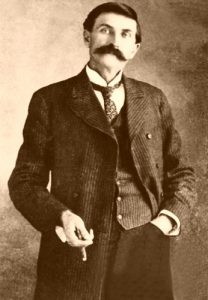

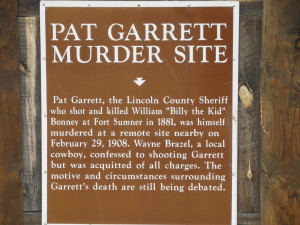

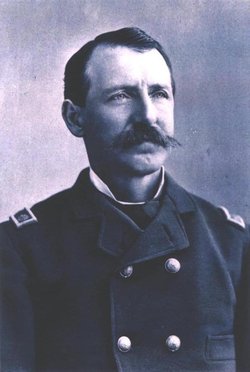

The story was a sensation. It appeared in newspapers around the country, and triggered intense speculation. Pat Garrett was brought out of retirement to investigate, and the Pinkertons were engaged. There was a shootout at the Wildy Well line camp, a made-for-Hollywood, real-life adventure that left Garrett in retreat and one of his deputies dead. Two years later Oliver Lee and his ranch hand, Jim Gililland were tried for the murder of little Henry. They were acquitted and there ends the body of uncontroversial facts. All else is gossip, partially supported conclusions, or dead certainties, depending on the social filter of the speaker. Even today there are Fountain folks, and Lee folks, and they're passionate.

"Who Killed Col. Fountain? A new book tries to solve one of the greatest Old West mysteries. " a review in True West by Mark Boardman.

At the time of the disappearances there were two local factions battling for economic and political power. They happened to be called Republicans and Democrats, but wariness is advised in choosing sides based on those labels. Some modern commentators, keyed to twenty-first century politics, and trying to support their Lee-ness, note that Fountain called himself a "Radical" Republican. They don't mention that Fountain explained the term as a desire to eradicate slavery in all its vestiges and legacy. The politics of southern New Mexico at that time divided along the major fault line of the nineteenth century, the Civil War. It was still being fought, and its outcome was unsure.

Old Confederates from Texas settled in New Mexico in the post-war years, and voted for Democrats. The Union men voted Republican. In some parts of the country the real politics was between two factions of Republicans, the Stalwarts and the Half-Breeds (allied or not with President Grant's followers), but in New Mexico, the battle lines were North and South.

The Fountains were sure their family members had been murdered because of Albert Fountain's cattle-thief investigations. They were certain Oliver Lee, a chief rustling suspect, was responsible, and believed Lee's neighbor, and bitter Fountain political enemy, Albert Bacon Fall, had a hand in the deed. Albert Fall, politician and attorney, questioned whether any crime had been committed. There were no bodies, therefore no murder. Albert Fountain was probably hiding out in Cuba, starting a new life away from his overbearing wife.

Time passed, the notoriety of the thing multiplied, and the Governor offered a reward, hired the Pinkertons, and appointed a high-profile lawman to investigate. Pat Garrett, hero of the Lincoln County wars, famous for ending the career of Billy the Kid, was called back into service from his Uvalde, Texas ranch. After a few years of accusations and denials, he secured indictments against Oliver Lee, Jim Gililland, and William McNew. They went into hiding, but Garrett cornered his quarry at the Wildy Well line camp. Garrett was forced to retreat and one of his deputies died of his wounds. Lee and his boys skedaddled.

Since we've brought up Billy the Kid, unavoidable in discussing New Mexico Lawmen, let's get an unusual perspective on New Mexico's most notorious delinquent from someone who's thought about it a lot.

Lee complained that Garrett intended to kill him on sight, a credible claim since Garrett didn't have a reputation for taking men alive. Billy the Kid was not the only outlaw killed by Garrett while resisting arrest. Lee said he'd surrender to anyone but Garrett, and hid out with various friends. He spent considerable time with his neighbor from across the basin, Gene Rhodes, better known as Eugene Manlove Rhodes, southwestern writer, and author of "Paso Por Aqui" and other sagebrush fare. Rhodes himself is rumored to have had trouble with the law, and left the state for many years, to avoid arrest for murder by some accounts. Every aspect of the Fountain business has its own body of gossip. Eventually a surrender was arranged, and Lee and Gilliland were put on trial. Oliver Lee denied everything and hired Albert Bacon Fall to represent him in court. They got a change of venue to Hillsboro, New Mexico, and the verdict went for Lee.

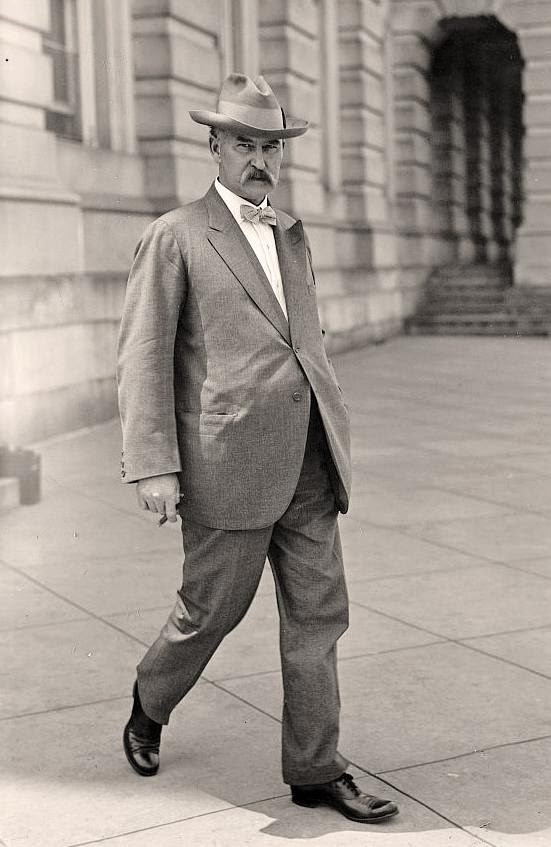

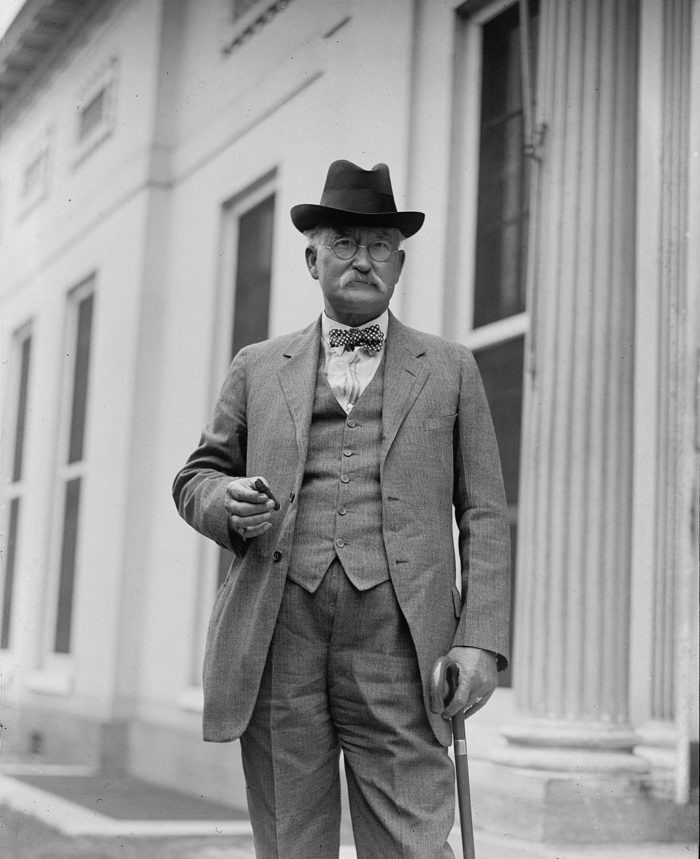

Albert Bacon Fall became the public face of the Teapot Dome Scandal. Other participants outran the mess.

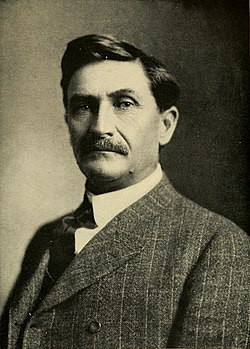

Fall himself was one of those larger than life creatures we find popping up from nowhere in American history. He went on to a storied political career. President Harding became a drinking buddy, and Fall went into his cabinet. Harding wanted him for Secretary of State, but the Department of Interior fit his skill set better. Fall signed some leases on the Naval Oil Reserve, allowing his friends, Harry Sinclair and Edward Doheny, to drill for oil. Some unsecured loans Fall received from Doheny were called bribes by a federal prosecutor, and when a jury, not in Hillsboro, agreed, Fall spent nine months in the Federal Prison in Santa Fe. The other side of the bribe allegation, Doheny, was found innocent of offering a bribe, and Harding's luckless drinking buddy became the fall guy for the Teapot Dome Scandal.

An amazing depth of hearsay has settled in around the Fountain disappearance. Deathbed confessions, related by third parties, often drinking heavily, provide details of the Fountains' fate that have substituted for an agreed truth. They appear in several books, and some of them might be true.

None of these stories ever get to a conclusion, and they are hopelessly intertwined. How can we get cowboys, bandits, lawmen and flying saucers so mucked up. That's the land of enchantment. Click the picture for more head scratching.

Albert Fountain Jr. claimed, shortly before his death, to have received a deathbed confession from one of his father's murderers. He refused to disclose the name because, he said, it could do no good at that point, and would do undeserved damage to the reputations of living descendants. Lee and his boys were not the only suspects. Many people, even today, hold out for professional hit men, picking them from the panoply of western bad men operating in the area. Sometimes these variations are proposed by Lee sympathizers unable to fathom their man murdering a little boy.

One bit of speculation seems certain. There were people alive at the time who knew what happened to the Fountains. Several people probably held direct knowledge of their fate, and they may well be the source of some of the rumors and gossip about the disappearance. Another bit of speculation is less certain, but compelling: people alive today probably know what happened to them. Still, we will not see a truth commission arise. If you want to know why, consider the comments above of Albert Fountain Jr. Then visit the Tularosa Basin, and get to know the ancestors of the main suspects, and the victims. You will find estimable people on both sides. The partisanship of 1896 has morphed into family pride and modern politics.

The cybershpere is scandalously lacking in good sources about Eugene Manlove Rhodes. Someone should do something about it. Here's a pretty good account from a blogger.

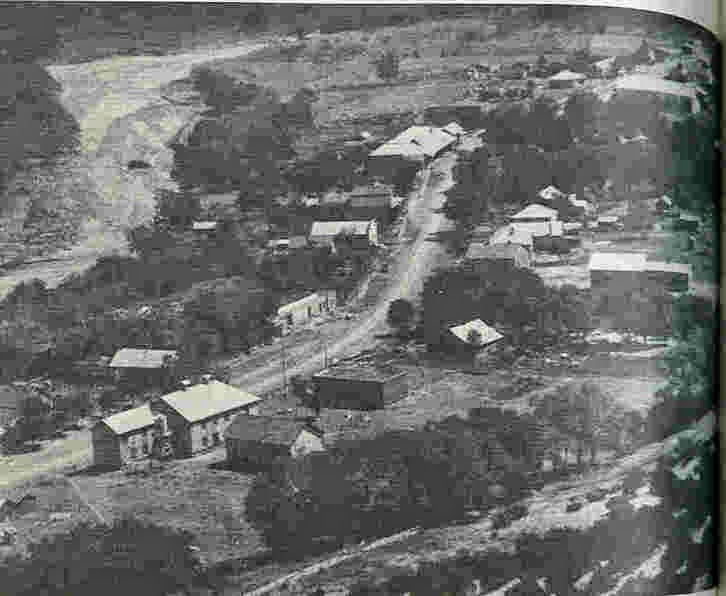

Hillsboro, New Mexico is a place worthy of its history. It was nearly wiped out in a 1914 flood, and is now a ghost-filled, non-ghost town. This picture of the old Hillsboro Jail is courtesy of Paul Ragsdale Edwards. Yes, this was most likely Lee's residence during the trial, after which he was taken to the Otero County Jail to await trial for killing deputy Kearney.

The title of this page is "Lawmen of Southern New Mexico," and it's worth keeping in mind that Fountain was not a lawman in the official sense. He was a private investigator for a business enterprise. Lee, Gililland, and McNew, on the other hand, were lawmen. They were deputy marshals for Dona Ana County at the time of the alleged murders.

Garrett, of course, was a bona fide lawman, but he didn't cover himself with glory in the Fountain investigations. He survived the trial by ten years before being shot in the back while on his way to Las Cruces. Two other men were present, and one of them claimed to be the shooter, acting in self-defense. He was defended by Albert Bacon Fall, and acquitted. The other man present at the shooting was not called as a witness. There is an entire cottage industry of sleuthing into this old west murder, with a rogues' gallery of hit men.

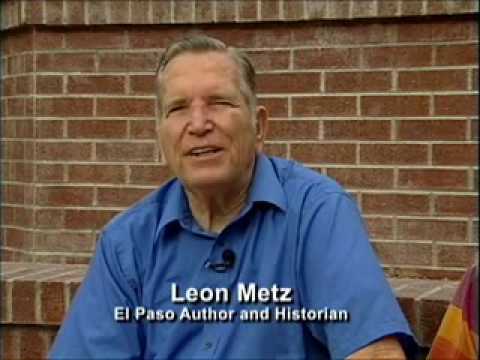

The disappearance of Colonel Albert J Fountain is generously covered in the nation's literature. The two preeminent southwestern historians, C. L. Sonnichsen, and Leon Metz, do excellent jobs of playing back the known facts, the credible gossip, and the incredibly complicated social setting. Their books, "Tularosa, Last of the Frontier West," (C. L. Sonnichsen, 1960), and "Pat Garrett, the Story of a Western Lawman," (Leon C. Metz, 1973), are must-reads on the topic. A more recent treatment (2007) by Corey Recko, "Murder on the White Sands," parses out the facts and suppositions, and recounts some of the more famous deathbed confessions. Various fictional treatments have appeared, notably the short story, "Little Henry," in the collection, "The Soul as Strange Attractor," which considers the sorry legacy of the killings half a century later.

Arizona has gotten a little something on the web about the late Dr. Sonnichsen. More than Texas or New Mexico, at least.

By the way, my initial interpretation of Herb Riffe's story was influenced by the flying saucer passion simmering around Alamogordo in the mid-1960s. It was not influenced by a then awakening mythos of airship landings in 1896-1897. It was years before I heard about an exploding airship blowing up Judge Proctor's windmill in Aurora, Texas. There were many other sightings, and a local farmer barely escaped kidnap. So far as I know even Albert B. Fall never suggested the Fountains were grabbed by men from Mars.

Mr. Riffe passed away in 1969 before I realized his story of a disappearance on the White Sands was not a ghost story. I missed the opportunity to discuss the Fountain matter with him, but I know which camp he was in. He mentioned Oliver Lee more than once. "A fine figure of a man," he told me. "I saw him riding down there among the cotton woods. Sat his horse like a general. Good, upstanding man. No one fooled with him." Oliver Lee died in bed, an old man, loved by many, respected by most.

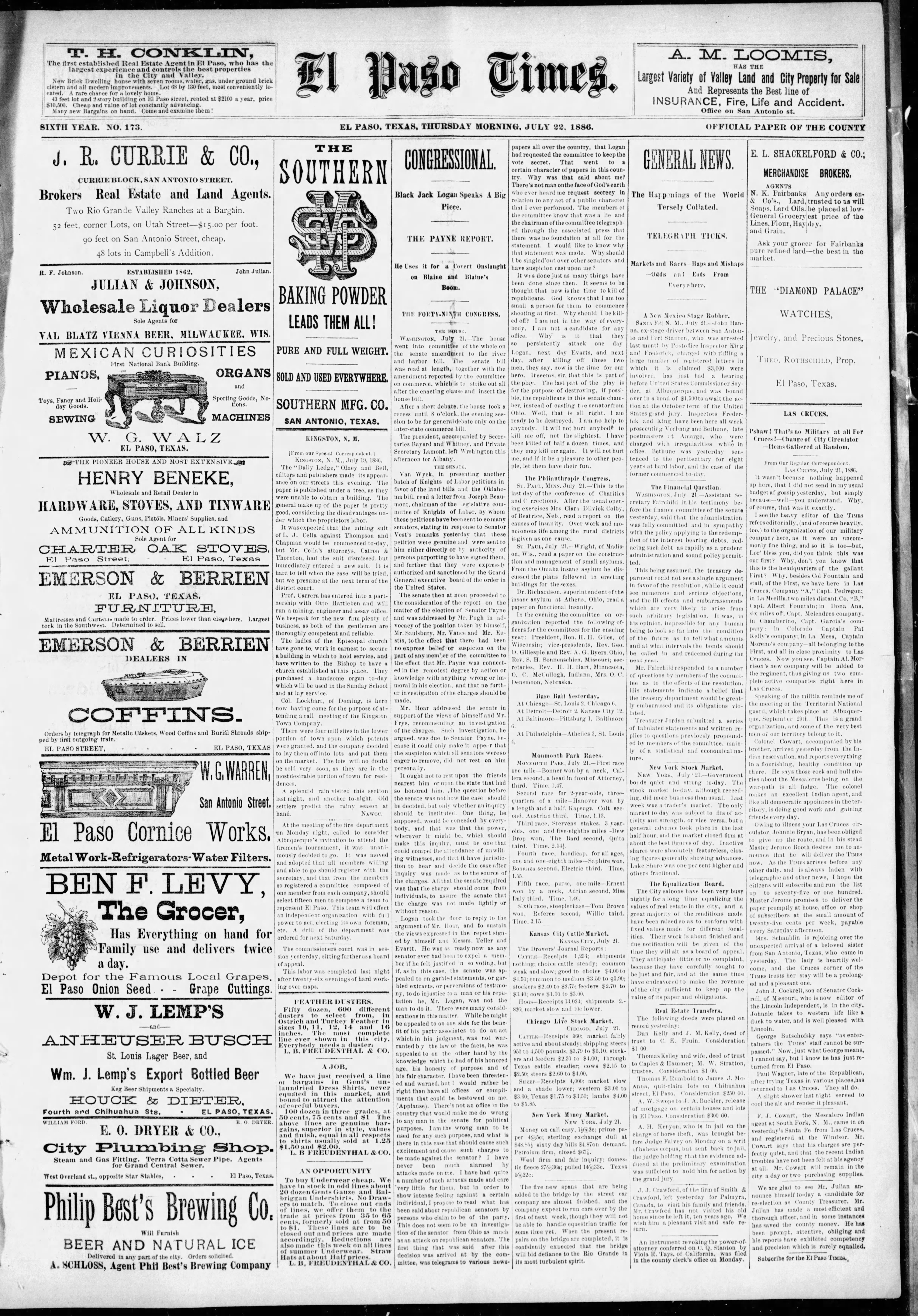

Have a look at the news clippings selected in the panel at upper left. They give a feeling for the temper of the times, and do a good job of recalling the politics and culture. The other links on the page give a good summary of where things stand today.

If you want to get a feeling for the geography of the business, you can poke around with the maps below, and above left.

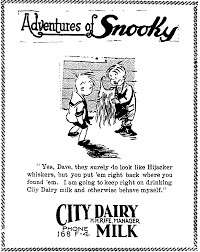

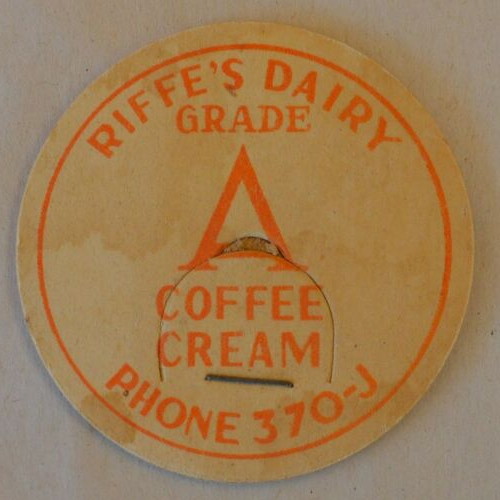

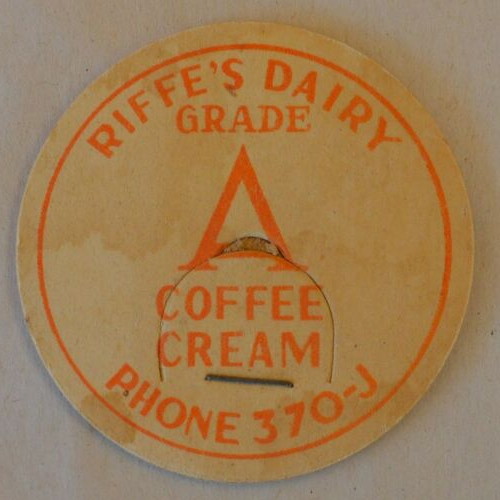

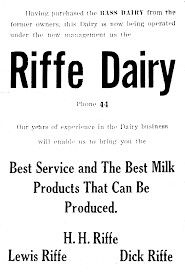

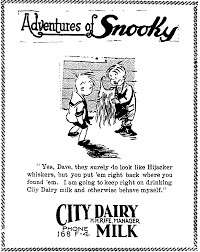

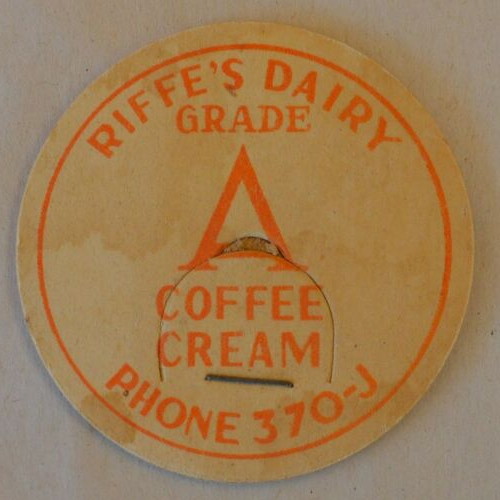

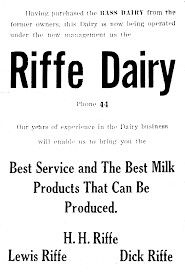

Herb Riffe was born in Kentucky in 1888, lived in West Virginia until 1911, and New Mexico after that. He passed away in 1969, his wife Minnie passed in 1973. Herb managed the Alamogordo City Dairy for many years beginning in 1925. He and his sons bought it in 1946. The Snooky cartoon below was a weekly advertising feature created by Riffe. A little of this history is found at the links under the pictures below, courtesy of the author, Bill Lockhart.

Menu of maps.(See where history occurred)

Herb Riffe was born in Kentucky in 1888, lived in West Virginia until 1911, and New Mexico after that. He passed away in 1969, his wife Minnie passed in 1973. Herb managed the Alamogordo City Dairy for many years beginning in 1925. He and his sons bought it in 1946. The Snooky cartoon below was a weekly advertising feature created by Riffe. A little of this history is found at the links under the pictures below, courtesy of the author, Bill Lockhart.