Dateline: November 20, 2020

The Battle of Vassar Hill

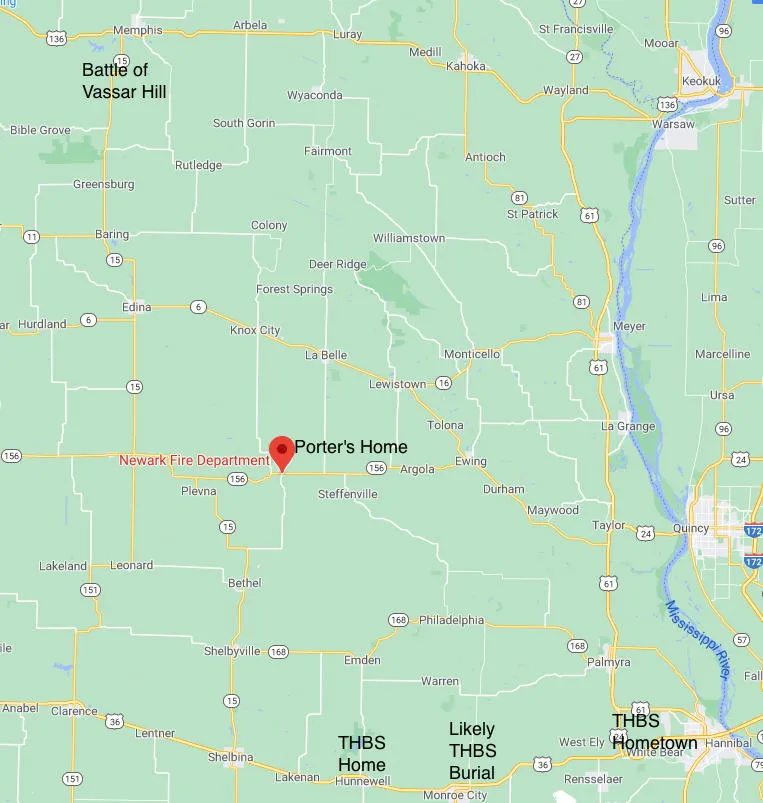

Thomas Hart Benton Stasey (hereafter referred to as THBS) was fatally wounded in Scotland County, Missouri, on July 18, 1862, in a Civil War battle variously called the Battle of Pierce's Mill (by Union forces), Vassar Hill (in local histories), and Oak Ridge (by the Confederates).

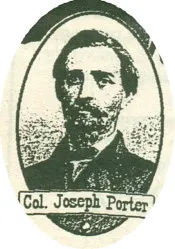

A force of about 280 Federal troops under Major Clopper met a force of about 125 Confederate troops under Colonel Joseph C. Porter a few miles south of Memphis, Missouri, and immediately south of the Middle Fork of the Fabius River. Estimates of troop strength have been controversial since the day of the battle owing to conflicting reports, official and anecdotal.

The Confederates arranged to fight from ambush, not to hold the ground, but to "try the mettle" of the Federals, according to the remembered words of Colonel Porter. The Union forces suffered disproportionate casualties, and declared victory after harrying the Confederates on their way.

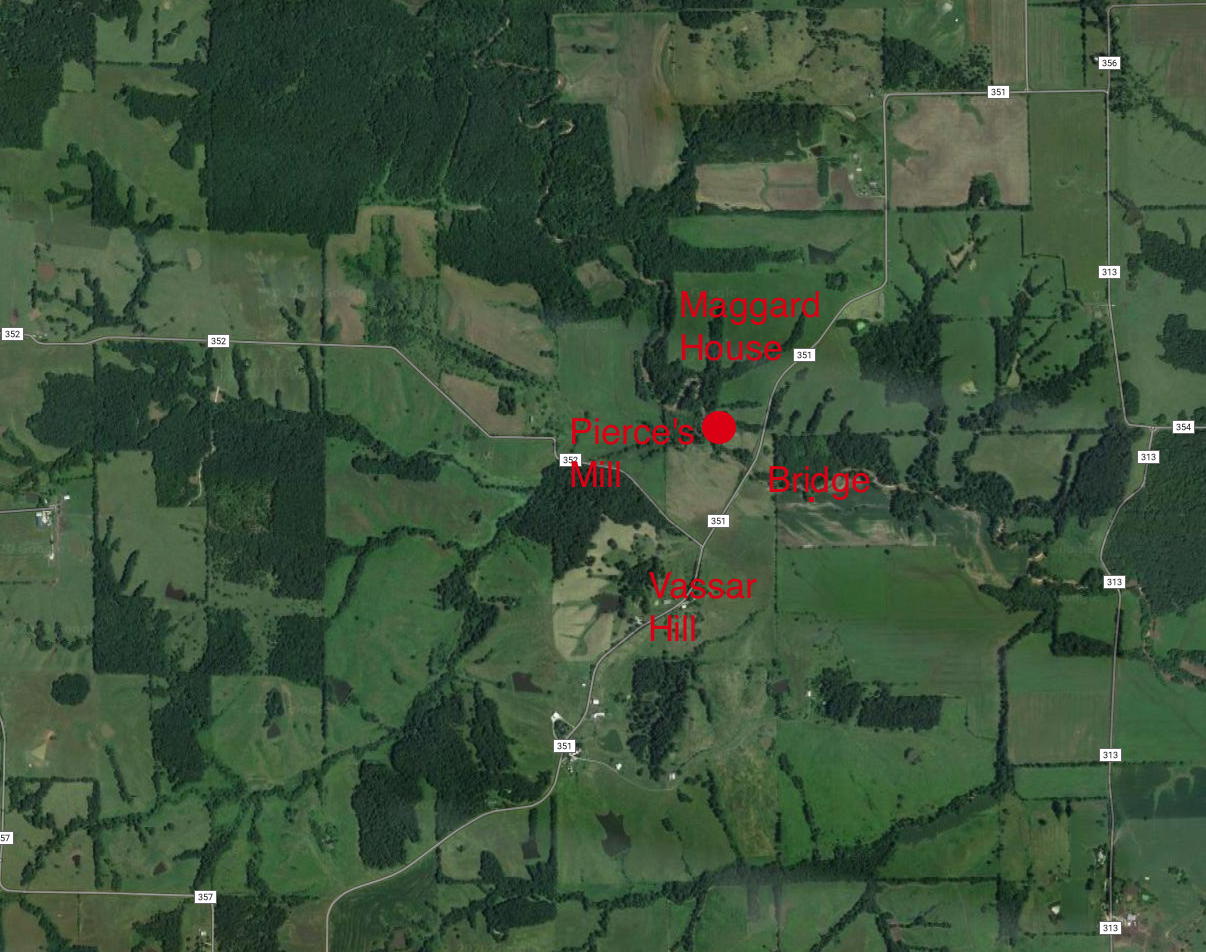

The battle was fought on or near Vassar Hill (Scotland County Missouri, Range 64N, Township 12W, Section 7), and local histories have labeled it The Battle of Vassar Hill for that reason. The Union forces named the battle for nearby Pierce's Mill, a landmark they passed just before making contact with the enemy. Colonel Porter called the location of the battle Oak Ridge.

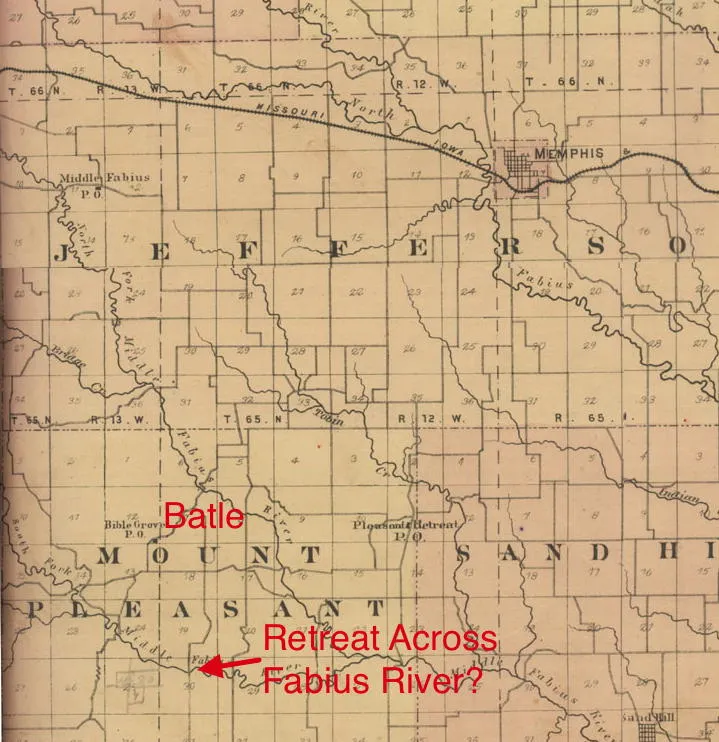

A mile or so south is Bible Grove, Missouri, an unincorporated, sparsely populated settlement. It formerly had a post office, but now consists of a few houses, two churches, their attendant cemeteries, and a school.

The records of the battle consist of sketchy military reports written by the Union Army, some mentions in the county histories written for the 1876 centennial, and the book, “With Porter in North Missouri,” written in 1909 by a Confederate participant, Joseph Mudd.

Mudd rode with Porter, took part in the battle and continued south with him as he eluded the pursuing Union forces. Mudd’s account is by far the most detailed, and has the only known account of THBS’s death. And, no, this Joseph Aloyisius Mudd is not the brother of Dr. Samuel Mudd, as often reported by those hoping for a simpler narrative.

Dr. Joseph Aloysius Mudd (1842-1916), Missouri doctor, confederate soldier and author, was a cousin to the more notorious Dr. Samuel Mudd of Maryland, who set John Wilkes Booth's leg after he broke it leaping from Lincoln's box in Ford Theater. Samuel and Joseph shared a great-great grandfather, Thomas Henry Mudd of Charles, County Maryland, 1707-1761.

Whether Dr. Samuel Mudd had anything more sinister to do with Lincoln's assassination remains controversial, but in the interests of muddying the story with some idle coincidence, our Joseph Mudd was born in Lincoln County, Missouri, edited a newspaper there, and wrote a history of the county after moving to Maryland. He worked for the Washington DC water department, and farmed in Prince George's county. He died in Hyattsville, Maryland in 1916.

The battle commenced on a bridge over the North Fork of the Fabius River and ran southward along the road over Vassar Hill. Pierce's Mill, a bit upstream from the bridge, stood on the road leading to the bridge at that time, but had nothing to do with the battle. A satellite map of the area today is nearby, annotated with the approximate location of the mill, which, like many landmarks of the battle, no longer exists. It links to a comparison of old plat maps, showing how the roads and parcel ownerships were displayed in previous times.

The battle, in brief, consisted of Confederate Colonel Joseph Porter's forces (widely derided as irregular bushwhackers, guerrillas, and outlaws) ambushing a force of Union cavalry after Porter's raid on Memphis, Missouri. Porter stationed a rear guard on the bridge, pretending to destroy it, with instructions to lead the pursuing Union forces southward into ambush. Union forces attacked the ambush several times suffering disproportionately great losses. They retired from the field and Porter hastened southward in a rapid, southerly retreat, hoping to link up with other Confederate forces south of the Missouri River.

The geography of the battle is elusive, partly because the roads, and maybe the rivers, have changed course, but also because of unlikely distance estimates. If you drive along the current road, using historical accounts to imagine where referenced incidents occurred, the events and geography don't reconcile. Some of that is owing to the passage of time: timber and brush have disappeared, and house locations have changed over the intervening 158 (as of 2020) years. One of the casualties of time is the road on which the battle was fought. It's no longer there (see below).

There is another big problem. The dimensions of the battle are problematic. Joseph Mudd's book, "With Porter in North Missouri," is the best historical source. Mudd participated in the battle but his description mentions distances that are clearly wrong. He tells us his unit rode about a mile across the bottomland from the Fabius River Bridge to the hills and brush beyond (see plat maps link above). They rode, he tells us, about two and a half miles to the ambush site.

The bridge, and Vassar Hill are located in section 7 of Range 64 North, Township 12 West. A section is a one-mile square. The current-days plat map in the link above shows this section 7. Two and a half miles south of the bridge would locate the ambush well south of Bible Grove, completely outside section 7, contrary to all accounts.

Porter's troops are unlikely to have traveled so far from the bridge. They probably proceeded at a fast trot (8 miles per hour). Mudd tells us the march was "fairly rapid." It would have taken them about twenty minutes to go two and a half miles.

At a fast gallop Porter's men could have been in position after only five minutes (30 miles per hour), but that means it would have taken Union forces five minutes to gallop into the ambush after meeting Porter's men on the bridge. When the Union forces engaged the ambush, Mudd specifically mentions they were "galloping," but Mudd indicates he heard gunshots at the bridge and soon thereafter the enemy reached the ambush, trailing Porter's rear guard by less than a minute.

Mudd also tells us trooper Durkee, one of Porter's rear guards, was unhorsed during the initial engagement at the bridge, but made it back on foot to Porter's lines before the second Union attack. A man hiking through heavy woods and brush to avoid the roads, would have needed nearly an hour to cover two and a half miles. That timing is inconsistent with Mudd's accounts.

Captain Rowell, part of the first Union charge into the ambush, estimated the distance from the bridge across the bottomland to the wooded hills at ¼ mile. That estimate conforms closely to distances we see on the Plat maps (see ilink above). If we recalibrate Mudd's estimates, taking one of his miles to be about a quarter mile, we would place the first ambush about 2/3 miles from the bridge, a distance covered in about five minutes at a trot, and in less than two minutes at a gallop.

Those times are consistent with Mudd's action description, and it would have taken Durkee about 15 minutes to get from the bridge to the recalibrated ambush site on foot.

Local historian Jack Brumback has researched the battle, and although his work is out of print, it can be found in the Hannibal Library, and other places. Here's what he tells us about the battle.

County History by Jack Brumback: REBEL OFFICER DIED AT BIBLE GROVE, MO. "On the 20th day of July, 1862, Captain Tom Stacey of Colonel Joseph Porter's command died of wounds he received in the battle of Vassar Hill. He died two days after the battle in a log house of Rudolph March (located 1/4 mile southwest of the battle site) and 1 1/2 mile north of Bible Grove. The Dunne family now owns the land, where the house stood. Just north of the log house was the location of the battle. The battle was fought on the old road east of the road that is there today...Capt. Thomas Stacey was raised in Miller Twp. in Marion Co., Missouri. Stacey died July 20, 1862, in the Rudolph March located in NE 1/4 of SE Quarter Section 7 Township 64N Range 12 West northeast of Bible Grove."

Brumback, who misspells "Stasey" as "Stacey," pinpoints the location of the battle for us, and, helpfully, tells us it was on a road that no longer exists. The 1876 Plat Map of Scotland County, Missouri, might give us the location of the "old road." The above plat map comparisons include an annotated 1876 map showing the possible location of events.

The link allows comparison of several plat maps including current era, 1930, 1898 and 1876. An 1858 plat map, almost ideal timing for the battle, also exists, but it contains only land parcel boundaries, and no indication of roads, rivers or other surface features.

Mudd tells us Lieutenant Stillson, a Federal soldier, was pinned under his dead horse during the battle, and that THBS was wounded trying to free him. One of Mudd's Union correspondents tells us Stillson fell at the "angle in the road." Based on our recalibration of Mudd's estimates, we suspect this "angle" was the fork on the 1876 map where the east and west roads diverged. If so, that would be the place Stasey received his mortal wound. If that was the left-most part of Porter's line, then the ambush extended eastward from there about a quarter of a mile (assuming 150 men at 6-10 foot intervals), approaching where the road jogs south down the section line.

This location for the battle fits the descriptions we've been able to find. Mudd says the Union survivors of the first ambush continued on the road, into a safe zone where they found a "dim road" back north to their lines. There was a farm in that area, owned by Phillip Purvis in 1876, and the mentioned trail could have been a farm trail.

As to THBS's fatal wound, we can credibly speculate it occurred between Union attacks when it might have seemed reasonably safe to venture into the road. We know Clopper's men fired several volleys from their mustering point north of the ambush site during these intervals. Porter's men were instructed to lay low and hold their fire between attacks, so these volleys were mostly ineffective. THBS, if his grandson (our grandfather) is an indication, would not have felt obliged to heed such an order, and was probably laboring to free his union prisoner during one of those volleys. I can hear my own grandfather matter of factly describing such a decision, in my head of course, since he never spoke of the battle and likely knew nothing about it.

Brumback confirms information also posted by the March family, that Stasey died at the home of Rudolph March two days after the battle. Brumback says March's house was ¼ mile southwest of the battle site.

We've annotated the 1876 plat map with these speculations, but we should also note the "angle in the road," where Stillson fell, could also be the point to the east of the annotated battle site where the road jogs south. Then the battle would have occurred mostly on the north-south part of Brumback's "old west road" and March's log house might be the "little log house" mentioned by some of Mudd's Union correspondents as their mustering place from which they mounted successive attacks.

That seems unlikely because it would have had Porter's men arrayed on the west side of the north-south segment, with their backs to the oncoming Union troops. We know from other reminiscences of the March family that their children hid in the cornfield behind the house, and it would surely have occurred to someone to ride across the field and strike Porter from behind, rather than around the road to be ambushed, time after time.

After the battle Mudd tells us Porter's men rode south and presently crossed the Fabius River a mile or two above the ford on the Memphis-Kirksville road. The 1876 Plat Map shows Brumback's "old west road" going south across the south fork of the Middle Fabius about two and a half miles south of the battle. From Mudd's description of the conversation he had with Stillson during that time, it sounds like they reached the river quickly, and at a moderate trot, they would have covered the distance in about half an hour. That seems to comport with other information.

There is some indication the course of the Middle Fabius River has changed, based on Plat Maps from 1876, 1898, and the current era, and that might have moved the location of the bridge, a tenth of a mile or so. It doesn't change any of the speculations above.

Mudd, quoting Stillson, gives us an account of THBS's appearance, and a hint of his personality. Mudd also gives us personal accounts of THBS, some less flattering. We've excerpted the accounts nearby, and, although they are the words of old men remembering the romantic adventures of their youth, they are as close to a contemporary accounting of THBS as we're likely to have, other than his letters.

Who in the world cares about Vassar Hill?