Dateline:Aug 15, 2022

Comments?

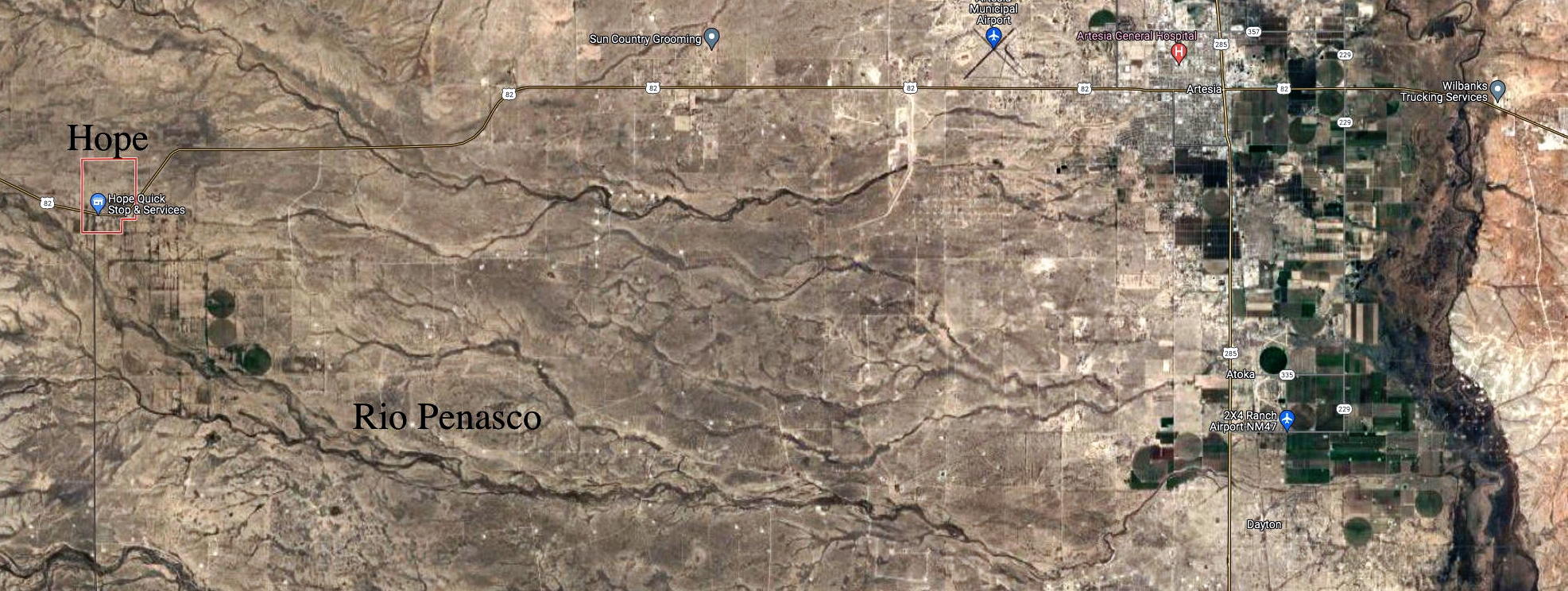

The drive from Cloudcroft, New Mexico toward Carlsbad is pending Hope, beyond Hope, or, briefly, in Hope. The tiny village has been a curiosity for decades. Why is this town way out in the Chihuahuan Desert?

On a recent drive down the eastern slope of the Sacramento Mountains we followed a brimmed-up Rio Peñasco through lush fields full of livestock, but with less farming than remembered. The Peñasco gouged a wide canyon below Cloudcroft over centuries of violent flash floods, but is often just a dwindling trickle. On this day it flowed handsomely all the way down.

In the eastern foothills, near the lower Weed road, Rio Peñasco disappears, and one supposes it dribbles out into the porous sand of the high desert. In fact, it goes another forty miles across the parched plain to the Pecos River. These days the Peñasco riverbed is normally dry before it reaches the Pecos, but flash floods revive its old purpose as a tributary to the more famous river.

In the late nineteenth century the Rio Peñasco increased its flow for a few decades and enticed hundreds of people to settle nearby with their cattle, sheep, orchards, and hopes for the good life. At first they lived near the river and lived in dugout-like homes they called Chozas. After a few flashfloods they learned to build further back.

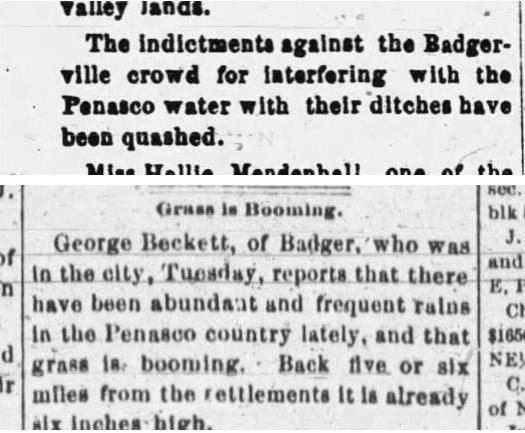

The settlement was known as Badger, or Badgerville, reputedly a comparison of those Chozas to badger holes. That name may have been mostly used by outsiders, and maybe in a how-can-they-live-like-that(?) way. The village later renamed itself Hope, and that decision inspires myth.

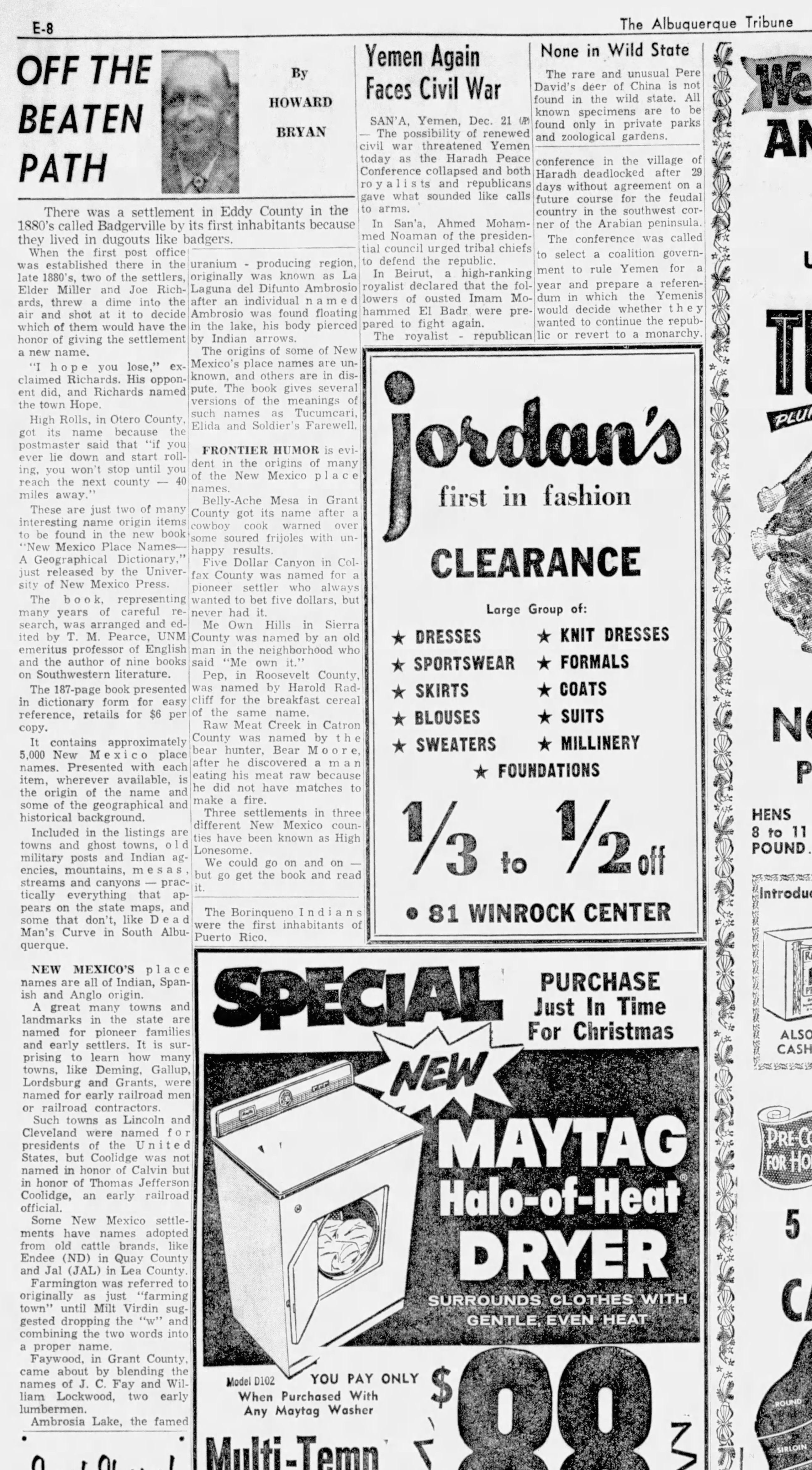

The authoritative version of the story comes from Robert Julyan's book, "The Place Names of New Mexico." His account is copied, pasted, summarized and misquoted all over the Internet. Here's his story.

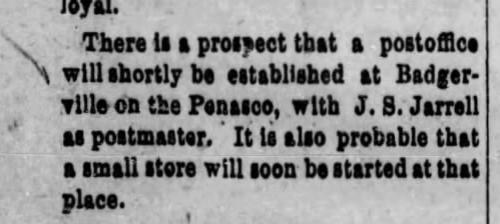

When this community was settled around 1884, its residents called the place Badgerville, or simply Badger, because they lived in dugouts, like badgers. This name would not serve, however, when the growing community needed a PO. The most popular and widely accepted explanation of the present name is that two early settlers, Elder Miller and Joe Richards, discussing who should give the name, tossed a dime in the air and shot at it with pistols to settle the issue. "I hope you lose," exclaimed Richards. Miller did, and Richards chose the name Hope. Richards's brother, J. Allen Richards, later wrote, "I remember the story as being told many times and that Joe did name the town Hope as a result of the shooting match." But one researcher has said that storeowner Jasper Gerald hoped for a PO at Badgerville and mail carrier Tom Tillotson hoped to expand his stops and increase his income, and the name resulted from both their "hopes" being fulfilled.

This is a good story and may call up the vision of some alkali-dusted old timer holding forth in the yellow glow of kerosene lamps, over a sudsy glass and a polished bar. If we take it to be anything more than a twice-told tale, it has some problems.

First, there's the premise that Badger and Badgerville were not suitable names for a post office. Nine states in the United States have post offices named Badger, and Canada has a Badgerville. As to the "most popular and widely accepted" story, timing is everything. The Hope, New Mexico Post Office was established in 1890. Arthur Elder Miller, known as Elder, was eleven years old in 1890, and Joe Richards, aka Joseph O Richards, was sixteen. The storied gunplay amongst such tender youth is believable for the time and place, but not the part about them choosing the name for a post office.

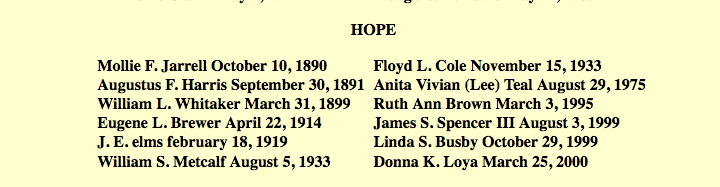

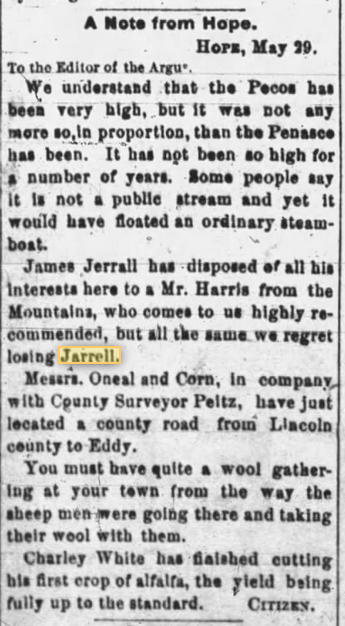

Mr. Julyan says shopkeeper Jasper Gerald may have chosen the name. This is perhaps a typo, or misremembered name. The postmaster of the first Hope, New Mexico post office was Mollie (Molly) Jarrell, married to James "Jasper" Jarrell, who seems to have started the first store in Badgerville-Hope. The Jarrells would have included the name of their proposed post office on their application to the Post Master General. Why did they choose Hope instead of Badgerville?

Newspapers in the late 1800s used the name Badger (or Badgerville), and after the post office opened they used both Badger and Hope, and sometimes Badger-Hope. Eventually, in the 1900s, Hope prevailed, and was used when the village incorporated in 1910. But, whence the name Hope?

Someone may know the story, or it may be explained in some unpublished letter or diary. The received stories recounted by Mr. Julyan, and others, seem mostly speculation, but we should point out his book was published in 1986, and follows closely the Hope Origin story in the book "New Mexico Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary ," by professor Thomas Matthews Pearce (1902-1986) published in 1966. See review linked above. Still, Let's toss some other speculative rings.

A newcomer to the Badger area at the time Jarrell set up his store and post office was William Daugherity. It's reasonable to think the Daugheritys were acquainted with the Jarrells. Daugherity was the constable, a school official, a freighter and mail contractor. He brought the mail to Hope from Seven rivers. He was rumored to be starting a newspaper. Daugherity's wife was, by the accounts of her children, a strong and influential person. She would certainly have discussed naming the post office with Molly Jarrell. Mrs. Daugherity was born in Hope, Arkansas.

One tempting explanation for picking Hope might have been more obvious at the time. Statehood for the New Mexico Territory was a widespread aspiration, and "hope" was a word often tied to the politics of the matter. Newspapers lectured about the hope of statehood, often with some imperative about the "only hope."

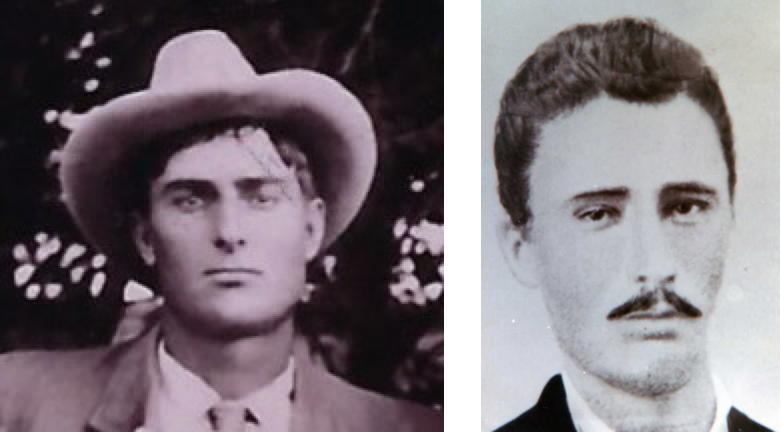

As to the Richards and Miller story, let's acknowledge its underlying strength. Elder Miller and Joe Richards were prominent local personalities, read characters, and the story of shooting a dime out of the air fits what little we know about them.

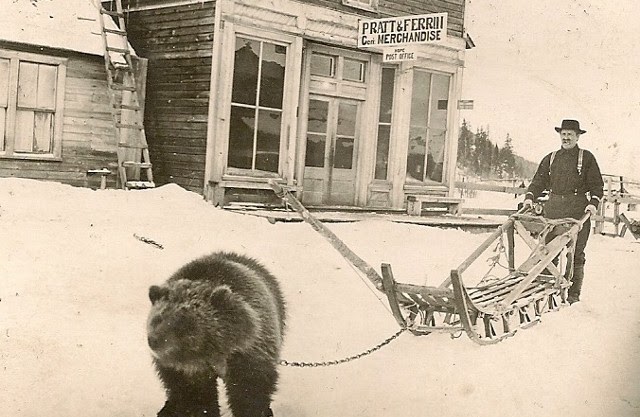

Joe Richards was a blacksmith, road contractor, businessman, and local politician. He moved to Artesia in the 1890s but owned land in the Hope area for years afterward. Further establishing Mr. Richards' local-color credentials is this story in the paper from January 10, 1910. "Joe Richards doesn't like bears. He was flapping his hat at one of those with the Mexican circus last week, and after several clumsy attempts the bear got one paw inside the hat and ripped it open from stem to sternus. Joe tried to buy the bear but the Mexican evidently feared he had evil designs on their pet and refused to sell."

He later worked for the state building roads.

The local paper tells us in April of 1926, "Joe Richards and the road machinery arrived at Hope Tuesday, and started work on the Hope-Y-O crossing section of the road."

YO Crossing doesn't appear on current maps. It is often mentioned, but not placed, in news stories, and water engineering reports. Among the few documented references we've found to its location is a 1939 report: "Geology and Ground-Water Resources of the Roswell Artesian Basin New Mexico." It says, "The...ridge, referred to by local geologists as the Y-O overthrust, is crossed by the Hope-Cloudcroft highway about 15 miles west of Hope." There are other references to the "Y-O Buckle," crossing the road 15 miles west of Hope.

A news story in 1913 locates Y. O. Crossing about 41 miles below Mayhill, which on today's road is about 15 miles from Hope. A 1975 news story mentions an F-111 crashing about 15 miles west of Hope, with debris falling near the Y-O Crossing.

Jared Bates, who knows the area, and has absorbed some of the early Hope lore, tells us the term "YO Crossing," referred originally, not to a river crossing, but to the ridge used by the early ranchers in getting to Roswell.

That would explain why there is an "Old YO Crossing Road" running southward from Roswell. It becomes county road 13, drops the YO moniker, and intersects highway 82 about 15 miles west of Hope.

As to why it's called the "Y-O" Crossing, consider this. There is a remaining bit of the old Runyan Ranch still operational in the foothills of the Sacremento Mountains just before the Rio Penasco trickles out into the desert. The founder of the Runyan Ranch, Tom Runyan, came into New Mexico in the 1870s as part of a cattle drive from the famous Y.O. Ranch in Texas. He, and others, started a branch office of the Y. O. on the Penasco.

A 1928 USGS report by N. H. Darton refers to the "YO ranch" in the foothills region. In 1926 the Albuquerque Journal ran a story about the highway department improving the Artesia-to-Cloudcroft road by eliminating the Y-O river crossing near the Y. O. Ranch. A 1923 story about an airplane crash near Hope, refers to a rescuer living at Y.O. Crossing. A 1930 Roswell paper refers to Jim Hinkle first discovering Y. O. Crossing. Hinkle, a former governor of New Mexico is claimed to have been on that Y. O. Cattle drive mentioned above.

YO Crossing is apparently a locally known place, undoubtedly associated with the New Mexico branch of the Y. O. Ranch, now largely forgotten.

Hope had signed up to sponsor a section of the new road from Artesia to Cloudcroft, and Joe Richards was building it. Jared Bates also tells us the old road from the mountains to Hope was on the south side of the Pensasco, it's on the north these days, which frames the road-building effort of Joe Richards, and others, as a more industrious undertaking. There probably was no real road into the mountains before their efforts, just some rough trails.

If all this is correct, then you can follow the trail of the old timers from Hope to Roswell, by driving up county road 13.

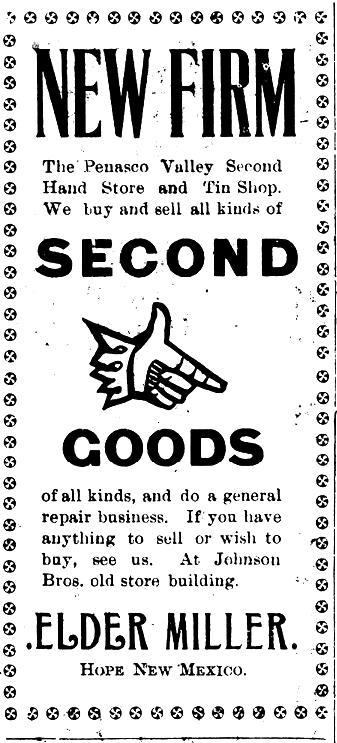

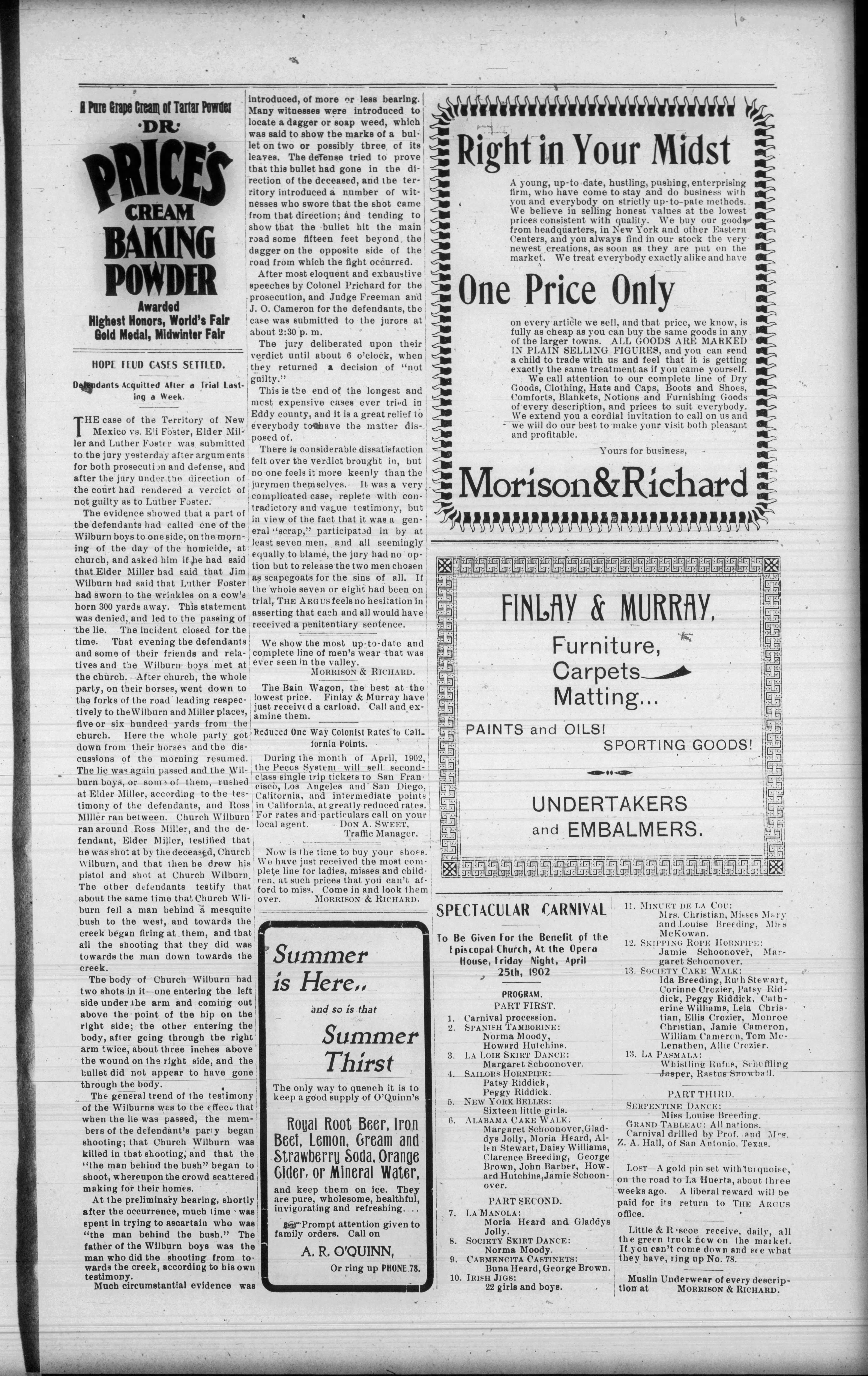

Elder Miller was a handsome young man of strong personality. He too was a blacksmith, a prominent position in pre-auto days, moved briefly to Artesia, but made his home in Hope. In 1901 he was indicted, but acquitted, of killing a man during a shootout. In later years he ran something called the "Pensasco Valley Second Hand Store and Tin Shop. See the ad nearby.

It's believable that Joe told barroom tales, probably told this one, certainly knew Elder Miller, and may well have included him with a prominent role.

They both seem to have been exactly the sort to figure in a genesis tale.

There's a chance Elder Miller and Joe Richards were agents in some other naming event. We know the names Badger, Badgerville, and Hope were all used during the 1890s. In 1893 a news article acknowledges the post office is named Hope, but continued to refer to the Badger people. Some stories seem to suggest Badger and Hope were two distinct places in the 1890s. By 1901 news articles referred to the Badger-Hope district.

When the twentieth century began, both names were in use, but the decade ended with Hope transcendent. The Carlsbad Current-Argus reported on May 22, 1949, "Once the town was [called] Badgerville when it was among the farms along the banks of the Peñasco, but that name was dropped and Hope adopted after the town was moved to its present site about 1905."

That's a date consistent with the ages of Richards and Miller, and could make an otherwise anachronistic incoherence focus into what it probably was, a barroom tale with truth around the edges. We might conclude Badgerville stayed down by the river, while the smart money, and saloons, moved with the post office up to Hope. A 1921 Carlsbad Current-Argus story suggests as much. "John Beckett, of Hope, was here this week, visiting his daughter, Mrs. M. C. Stewart. Mr. Beckett has made his home in Hope since 1884, in what is known as the old 'Badger' settlement."

The village incorporated in 1910, and in that year the U. S. Census used the name, "Hope, New Mexico," for the area it had labeled, "Precinct 3 of Eddy County," in 1900.

Another Version

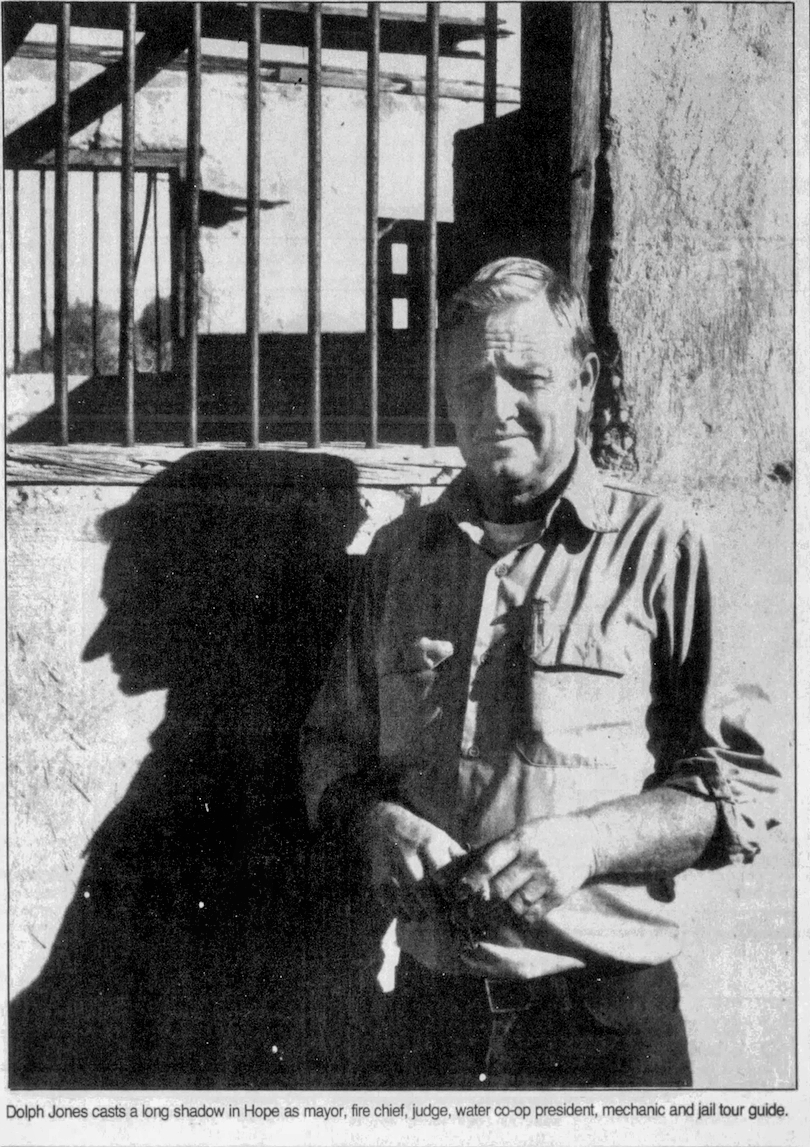

There is another version of Julyan's origin gospel. In 1987, then mayor Dolph Jones told reporter Bart Ripp a similar story but with these changes: The naming event was not the post office but the city incorporation in 1910; the participants were alleged rancher Joe Wood (in for Elder Miller) and Joe Richards; they "had a few drinks in Dad Shelton's saloon" (suspicions confirmed); they went outside to flip a coin; then the Julyan story resumes with the coin flip and gunfire.

Joe Wood was the blacksmith in 1910 Hope, and he's buried in the Hope South Cemetery. Joe Richards had moved on to Artesia by that time. This is probably just too good a story to confine itself to a constant cast of characters.

Wrinkles on a Cow's Horn

The nearby news stories tell about Elder Miller's shootout, but let's comment on a few aspects. The gunfight was between two groups of young men, members and friends of the Miller family, versus the Wilburn boys, and friends. According to news accounts, the shooting broke out because, listen closely, one of the Miller boys, "had called one of the Wilburn boys to one side, on the morning of the day of the homicide, at church, and asked him if he had said that Elder Miller had said that Jim Wilburn had said that Luther Foster had sworn to the wrinkles on a cow's horn 300 yards away. This statement was denied, and led to the passing of the lie," according to the Carlsbad Current Argus of Friday, April 18, 1902.

Great Gods! He swore to the wrinkles on a cow's horn at 300 yards?? In the ensuing gunfire, augmented by a mysterious older man firing from behind some distant trees, perhaps the father of the Wilburn boys, one of the Wilburns died. The cause of the shooting is almost indecipherable out of its rural, hundred-years-ago context.

Perhaps it helps a little to note that counting the rings on a cow's horn is a method of telling the bovine's age. In that far off time of limited cash supply, trading was both entertainment and business. Perhaps someone accused someone of lying about a cow's age, a shooting offense.

Hope, Railroads & Titanic

Hope, New Mexico is a vanishing town. It still has about 100 residents, down from 300 in 1950, and a high mark of around 1600 in 1910. Businesses and schools have been long closed, but the post office, churches and cemeteries seem to be functioning.

You may be surprised to know there is still irrigated agriculture in the area, probably from ground water. Satellite maps show several telltale irrigation circles south of the main road, and river.

The town has been declining since about 1914, but not from lack of enterprise. Some blame a failed railroad initiative. Hindsight now shows us the decline in the Peñasco annual flow, plus the 1933 adjudication of water rights called the Hope Decree, gradually emptied the Hope ditch and strangled the irrigation agriculture.

But the railroad story is nevertheless a typical Hope tale. The potted history favored by the Internet gives us a financier, a Brit named A. G. Ragsdale, who went off to London to gain financing, and sank with the money on the Titanic returning home. Some mention the possibility of fraud, since all the funds raised by Hope and Artesia folks also disappeared.

There are numerous, slightly different, incarnations of this story. As with the Badger-to-Hope tale, the Titanic-sank-the-railroad narrative has timing problems. The Titanic sank April 15, 1912, and there are news accounts years after that about the imminent start of railroad operations to Hope.

In July 1912 the Santa Fe New Mexican ran a story about Hope banker, H. M. Gage, meeting with Salt Lake businessman and financier, A. G. Liebman, to fund the immediate operation of the Artesia-to-Hope railway spur. The building of the railroad was deemed, "A lead pipe cinch." It doesn't mention the Titanic.

The Hope-Titanic story seems impervious to research. Contemporary papers don't mention it. The Hope Peñasco Valley Press was published during that time, and while it reports separately on the Titanic disaster and the Artesia-to-Hope railroad spur, it never connects them. This story of uncertain origins cycles through the newspapers at odd moments, with slightly altered details.

In 1992 the Santa Fe New Mexican cobbled up a story in which a Brit named Lord Jon Pierson of the Pierson Syndicate was in London seeking funding for the Hope railroad. He stowed the Hope railroad funding, gold bullion, in the Titanic safe. The story notes its lack of substantiation, but assures us the Titanic sank the Hope railway, and therefore, Hope itself.

A 1980 version of the story has the same general outline, but with important changes. Dolph Jones, the mayor in 1980, cited a newspaper in his possession from Derbyshire, England, which, he said, mentioned the sum of 12,500 English pounds raised for the railroad. The English financier's name was Phillip John Starkey. An Artesia businessman, J. J. Clarke, was said to have left a tape recording to the Artesia Historical Museum in which he testifies to having headed back to New Mexico on the Titanic, with the Englishman. Clarke later showed up empty handed in Hope, and blamed the loss of funding on the Titanic. The recording seems to be lost.

The 1980 story mentions an Artesia Advocate story from June 1912 about a mock memorial for the railroad, on account of the loss of the Titanic. The 1912 story can't be found.

In a 1987 version, Clarke doesn't go to England and survive the Titanic, but Starkey does. In this version, Starkey is a cousin of Hope merchant, Olin H. Ragsdale (see A. G. Ragsdale, above). None are mentioned as going down with the Titanic, although the money did. News accounts of the time name Clarke, a dentist in Artesia, as among early Hope railroad advocates, but doesn't mention his Titanic adventure.

The earliest story blaming the Titanic for Hope, New Mexico's demise is a 1937 AP concoction marking the 25th anniversary of the unsinkable ship's dunking. The story insists the Titanic safe contained the gold meant to finance Hope's railroad. It appeared in newspapers all over the country. Curiously, the previous year (1936) a similar story featured Dr. Pierson of London's Pierson Syndicate sinking an irrigation scheme in Texas when he went down with the Titanic (see nearby). Its author, Ulmer Smith Bird, was a writer and journalist in San Angelo, Texas.

Can any sense be made of this strange, reality estranged story? Just a little, if we're not too fussy about details. There was an engineering syndicate building railroads around the west and southwest about that time. It was called the Pearson (not Pierson) Syndicate, named for Frederick Stark Pearson. Pearson was an American engineer/financier, graduate of Tufts, who was building railroads, power plants, irrigation projects, and much else in both north and south America. In the 1910 -1914 period he was the principal in something called the Quanah Railroad.

Quanah is a town in west Texas named for the famous Comanche Chief, Quanah Parker. The Quanah, Acme and Pacific Railway was incorporated in 1902 with the declared intention of connecting the eastern states to El Paso. By 1910 numerous aspirational towns were ballyhooing and raising funds to get themselves on the route map to El Paso. These included New Mexico towns Roswell, Artesia, Cloudcroft, Dayton, and Hope. In each locale there were boosters raising funds and selling vigorously, hoping to get into Pearson's plans.

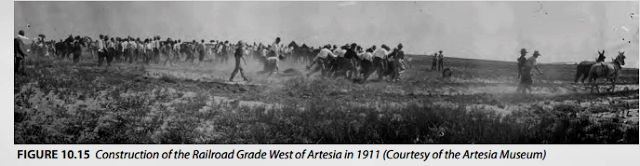

John C. Gage, called Parson Gage, was a booster for the Hope Spur. Money was raised and a plan enacted to start leveling a grade from Artesia to Hope. With construction about half way to Hope, and with the money running out, the completed portion was offered as collateral in a bond offering to complete it. The bonds didn't sell, and the project went sideways, declaring bankruptcy in 1914.

As all that was going on, the Quanah connection to El Paso became more and more unlikely. It was, in fact, never built.

Frederick Stark Pearson was an inspiring man with dynamic, far ranging interests and accomplishments. Just the sort you'd expect to show up in a half-baked tale of might-have-been. Pearson had a branch office in London and made frquent trips there to arrange financing. On one such trip his ship sank sending him and his wife to Davey Jones' Locker. The ship was not the Titanic in 1912. It was the Lusitania in 1915. Within the rigors of a barroom tale, ocean liner disasters are fungible.

If, in the first three decades of the 20th century, you'd gotten most of your information hanging around bars and listening to the chatter over a mind-numbing beverage, you could have sourced any or all of the Hope-Railroad-Titanic stories. In the dim light and pleasant ambience, names mutate, and details blend.

Hope Abides

A few newspapers have published from Hope over the years, including "The Hope Booster," published by N. L. Johnson, the "Hope Press," by A. M. Burnett, the "Peñasco Valley news and Hope Press," by I. P. Murphy and later W. E. Rood, the "Peñasco Valley Press," by Abe M. Burnett, the "Pecos Valley Press." Drop by the University of New Mexico library and they can pull the microfiche for you. Or, you could try "Newspaper Archive," which has copies of the Hope Peñasco Valley Press from 1909-1929.

There have been some oil drilling efforts around Hope, with predictions of another boom, but apparently all the holes were dusters. The Pearson (sometimes Pierson) Syndicate also backed American oil drilling, but we don't know if they funded the Hope drilling.

If you guessed there was trouble, both upstream and downstream, from the Badgerites ditching water out of the Rio Peñasco, you probably know something about New Mexico politics. Water rights are serious business in Pecos Bill's country, and have led to more shootouts and nefarious killings than all the wrinkles on all the horns on all the cows that….ok, but there has been a lot of trouble over water.

Noel Johnson's daughter, Francis, conveys the importance of the river to Hope's prospects in her father's obituary. Noel Johnson was a sure enuff cow hand. He was born in Texas during the Civil War and tended beef critters from New Mexico all the way north to Montana and the Dakotas.

In 1901 Johnson went to Hope, acquired a land claim that included continuous water rights out of the river, granted by President McKinley we learn, shipping fruit and hay to eastern markets. His daughter tells us the water ran year around until about 1919. Noel became a village father, and went into several businesses including mercantile owner, insurance, real estate, hotel owner, and newspaper publisher. In the late 1920s he was a principal in an unsuccessful oil drilling effort. You can read her account in the nearby link.

In 1933 the State Engineer, whose main job is water adjudication, engineered a solution to the water problems of southeast New Mexico that has since governed the Pecos River and its tributaries, of which the Rio Peñasco is one. It's called the Decree of Hope, because the adjudication of water rights in the even then rapidly declining town of Hope, was the catalyst that spurred settlement of long standing water disputes along the lower Pecos River.

Life Magazine ginned up a novelty number about Hope in 1950, since Hope-ites had elected a female mayor and city council. The town had only a few good years left. The last three high school seniors graduated in 1955. The elementary school closed in the 1960s, and area children now attend an elementary to the west at the turnoff toward Weed.

In the 1960s there was at least one store, and over the years filling stations and stores have popped up for a while. There used to be an empty police car parked on the highway to discourage high-speed scofflaws. Some have claimed being stopped for speeding in Hope, but before believing them, think of the Titanic.

Hope has continued attracting America's creative talents. A 1972 movie that helped found the Viet-Vet-as-dystopic-sociopath theme, "Welcome Home, Soldier Boys" features a bloody massacre set and filmed in, Hope, NM. The parched village is also a battle ground in the modern zombie mythos called World War Z. Oh well.

On our recent Hope transit there was no sign of life, no businesses, no water in the Rio Peñasco, and not even a tumbleweed crossing the road. The post office is still there. And the churches and cemeteries. Elder Miller is buried in one of them, but Joe Richards is in Artesia. Both died in their 60s in 1942.

If you stand in the middle of the highway and listen intently, you may hear distant, and faint rumbles. Don't mistake them for a ghost train. It's the sound of long-ago industry, busy people doing the important stuff of life, and perhaps an ever-stirring hope for better times, or another Krakatoa.

Who in the world cares about Hope?

You could send us an email if you prefer,

or comment via Facebook, below.

All comments will get an appropriate response.

The Life Magazine article about Hope, New Mexico is in the next two slides. Or, if you want to slip back to that time, have a quick look at the entire magazine.

Slide Show

Advance Slide

...

Wealth creation in the 1890s (Click to close)

In 1890 American currency was convertible to gold, and the quantity of gold held in Treasury reserves (think "Fort Knox") limited the nation's money supply. Wealth generation from invention, innovation, and land-use expansion required more currency, and 1890 legislation to meet this economic need allowed the coinage of silver.

Americans used the increased money to conduct normal commerce, but foreign banks considered the American dollar devalued. They began demanding gold for their dollars, and by 1893 American gold reserves had fallen by over 40%. People feared there were more gold notes than gold.

A shortage of gold could cause failing banks. Americans began withdrawing their money, and banks indeed failed. Since banks borrow money from one another, the failure of one caused the failure of others, all across the country. This panic, so called, although it is a completely reasonable response to economic incentives, led President Cleveland in 1893 to get the 1890 Silver coinage act repealed, and the banks eventually stabilized.

But then the old problem of inadequate money supply returned, and the dynamic, loquacious, joyously simplistic, William Jennings Bryan diagnosed the country's problems as being "crucified on a cross of gold." He was technically correct, and might have ridden this slogan into the White House if the 1896 Klondike Gold Rush, and one near Anchorage, had not supplied enough new gold (money) to replenish reserves.

It is important to remember that mining gold in Alaska did not increase the nation's wealth. The explosion of wealth during the late 1890s gushed from the explosion of innovation, invention, and entrepreneurial activity. It's creators were the inventors such as (among many others)

- Edison,

- Tesla,

- Hollerith,

- Froelich (gasoline tractor),

- Jenkins (motion picture projector),

- Hooker (mousetrap),

- Winton (semi-truck),

- Wilbur Wright (wing warping),

- Cowen (flash lamp),

- Judson (zipper),

- Reeves (car muffler),

- Fiske (rangefinder),

- Halsted (surgical gloves),

- Schrader (tire valve);

And by business people like many of the above plus,

- James Hill,

- J. P. Morgan,

- Andrew Carnegie,

- J. D. Rockefeller,

- William Randolph Hearst,

- George Eastman,

- and George Westinghouse;

And by educators including thousands of teachers, and local school boards across the country; and by the millions of Americans who helped create, and began using, the life-changing products and services of the 1890s.

America's wealth was baked into American life. The world, in the form of thousands of immigrants, recognized that fact by flooding onto American shores, streaming into the heartland, and adding to the accumulating wealth.

America did not have streets of gold, but it offered the freedom to exploit opportunity. It was not paradise, nor fair, nor equal, but millions rushed in, and few rushed out.

Every motive, incentive, justification and interest swarmed about in that boiling mixture, including the determination of a young American named Leon Czolgosz. He imagined he was doing everyone a favor when he shot McKinley, but his reward was swift execution in an electric chair powered by Nichola Tesla's AC power plant at Niagara Falls (Edison, who favored DC power plants, used his motion picture technology to film Czolgosz getting juiced to terrify Tesla's customers).

.jpg)

.jpg)

Even aside from the Village of Hope's creative legend making about trains, The Titanic, and the origin myths, Hope, New Mexico has inspired the talents of America's dreamers and doers.

Here is a little sample of the muse called Hope.

In 1971 a Warner Brothers movie called "Welcome Home Soldier Boys" defined the cliched treatment of Vietnam Veterans in popular culture. The climax, see nearby-linked Youtube video, was filmed in Hope, New Mexico.

The movie is incredibly bad, and the Hope scene is one of its worst. Still it's fun to see the old town on the silver screen. We found only one building in the movie still identifiable as one seen today on main street.

Running and walking coast to coast are frequent enterprises, often for fund raising. Ernie Andrus did it twice, first in 2013 at age 90, and again, the other way, in 2016 at 95. His hope was to raise funds for " the LST 325 Ship Memorial." Ernie was a World War II Navy veteran, and he tells us was use to lnd equipment and troops "on hostel shores."

As you've guessed, Ernie went through Hope, New Mexico. You can see what Hope was to him in a nearby video, and get a little idea about his efforts in his web site.

Steve Garufi

Steve Garufi made his second ride across America in 2011, and went through Hope. Here's how he introduces himself. "My name is Steve Garufi. I am a cyclist, hiker, photographer, and Colorado poster child in the Rocky Mountains. I'm a Licensed Professional Counselor, a "talk therapist" for my vocation. In 2008, I biked across America for the first time and wrote a book about it. On this page is Trip #2. My goodness, I realize how lucky I am to have biked across the country twice! :)"

Steve gives us an idea of the thrill of cycling down the mountain from Cloudcroft to Hope.

It's interesting to note how many people transiting the country on foot and by bike, do it twice. It's a common theme noticed in the more famous ones, from Edward Payson Weston in the late 1800s right on through today. Sadly, Weston followed the railroads and so, didn't go through Hope.

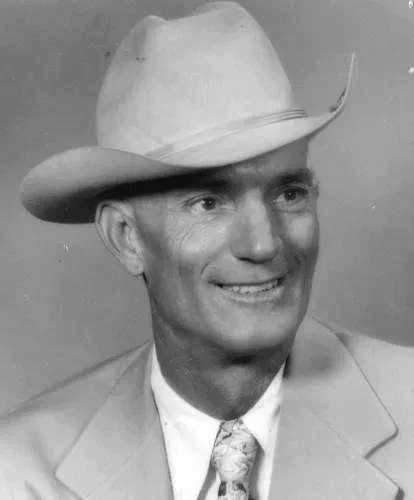

Everett Bowman

Hope, Arkansas claims an ex-president, but Hope, NM produced Everett Bowman, All Around Champion Cowboy of the World for the years 1935 and 1937. Everett was born in Hope, NM, in 1899 and died in Wickenburg, AZ in 1971.

Everett founded, among other things, the cowboy's Turtle Association, and even appeared in the movie, "The Great White Hope." He's in about every rodeo hall of fame ever concocted. He left Hope in 1913, which means he was shaped by Hope.

Bowman was one, but the most famous of, five Bowman brothers in the rodeo business. They all made their mark, but Everett was the star. He died in a plane crash in Arizona in 1971.

Here's how he was remembered in one of his hall of fame inductions.

Winner of 10 world championships in nine years, Everett Bowman’s dynamic leadership made him one of the great rodeo contributors to the advancement of professional rodeo. Bowman, born July 12, 1899, in Hope, N.M., won his titles during a career that spanned more than 20 years. Bowman won all-around championships in 1935 and 1937; tie-down roping championships in 1929, 1935 and 1937; world steer wrestling championships in 1930, 1933, 1935 and 1938; and the world steer roping champion in 1937. When the cowboys’ Turtle Association was founded in 1936, he was elected president, an office he held until reorganization of the CTA to the Rodeo cowboys Association in 1945. Most of the fundamental changes in rodeo that are now the bedrock of the sport came about under Bowman’s leadership: adding entry fees to prize money, fair and impartial judging, codified rules and regulations, humane treatment of livestock and minimum standards for approval as a professional rodeo. Bowman died in 1971 in a plane crash in Arizona.

World War Z is a mythical battle fought in the town of Hope sometime in the future. It's a big deal among zombie fans, and you find them in odd places, including driving through Hope.

The Bureau of Land Management BLM has a lot to say about what goes on around Hope these days. It's the old story of city slickers telling country folk how to live, and the country folk telling the city slickers to kick the asphalt off their brains and think for a minute. Here's Hotshot Hendricks reading the current dialog in an old, old play.

“What affects me is about 3,500 acres they say I can keep on using,” he said. “If we get another administration, they’re gonna say I can’t do it. They’re going to call it wilderness."

To which the city slicker replied, “This is part of the field office where we don’t have a lot of mineral activity. But they’re a good community. It’s important for us to come out here and hear their concerns.”

All inspiration is not equal, for example, the World War Z reference above. Here's another example. A Boston Yankee, self confessed, has this tale of going into the wilds of New Mexico during the WPA era. Your tax dollars at work. We won't bother parsing fact from fantasy here. I believe the correct term is cultural bias. Oh well.

From a recounting of the early days of the forest service in the Southwestern Region, Book 3.

Mr. Willard Bond, a Boston Yankee, is a graduate of Bates College and the Yale Forestry School. He arrived In District 3 in 1924, and was assigned to the Coconino National Forest to work on the Arizona Lumber and Timber Company sale. Bill was interviewed at his home in Nambe, New Mexico. Mr. Robert Ground was also present at the Interview, and contributed to the stories.

One of the things I remember was planning a recreational area with Clancy Waneka...

In a place called Hope, New Mexico. I worked on Hope with Clancy and we had $1,000 to build a recreation area. Well, after spending the night with an old character by the name of White over in Hope, and gettin' up early the next morning and gettin' a pail of water out of the irrigation ditch, after movin' the manure off the water surface, we got a pail of water and washed our face and hands. We didn't dare drink it. The only other available liquids there was Bourbon whiskey and beer. We had a very fine breakfast with Mr. White. This was in July but we had deer meat. He called it "summer beef." Where he got it, I don't know, except that it was a very delightful breakfast, grits and "summer beef."

Well, Clancy and I decided it was about time to do something for those people, they couldn't afford to drink whiskey all the time, and there wasn't enough beer in the country, no ice to keep it cold, and hot beer is a very unpleasant beverage. We looked around and asked about water. Old Man White said, "Yeah, there's a well around here; it's about 12 miles off," and he said, "The thing's over a thousand feet deep."

Right away Clancy's eyes lit up; so did mine. We had a thousand dollars, and we were thinking very seriously of the possibility of people at Hope gathering around a well an' bein' able to talk, or sit down, and get a pitcher full of nice cool water. An unusual drink; I don't recommend it, but it is an unusual drink. So we decided that we were gonna make a try for a water well.

We talked to some local drillers and found out that water was available at right about 800 or 900 feet and there was a possibility that it would cost about a dollar a foot. That left us with enough money for possibly a windmill or a hand pump, although I don't know who would've pumped a 1,000 foot deep well by hand. But we were thinking that way. We were a couple of young squirts and just full of ideas. The only thing I think was successful about Hope was the water well; it did come in at about five gallons a minute. We were successful in convincing the Washington Office that this was a good expenditure of recreational funds. We got approval and put 'er in finally, and put in a couple of picnic tables which you could build for about $10.00 apiece in those days. In other words, we set Hope up.

Thank God someone from Boston arrived when he did, to "Set Hope Up."

Finally, let's consider a local lad named Altus R. Boulden, living near Hope in 1945. He'd just turned 17 and his mother had finally consented to his joining the service to do his bit. A few days before he was to leave, the sun rose twice.

Altus went into the Army in February, 1946 and served in Italy until his discharge in 1947. His obituary in 2003 said he was known as "Lucky," and it was lucky that he didn't have to go to the Pacific to end the war over there. He couldn't have realized it when he and his mother and his future bride saw their early morning puzzle in the sky, but that was his ticket to a long life. He had a little youthful trouble in the early 1950s, but married, had a career with GE, retired to a ranch in northern New Mexico, and left children and grandchildren to ponder the miracle of their being here.

Hopes of America

Twenty-five states have communities named Hope. We disregard the many other towns called New Hope, Mount Hope, Greater Hope, and so forth. Most of the "just Hopes" are tiny, and often ghost towns. A few are marked as historic locations.

The most significant American Hope is in Arkansas, population over 10,000, with a former president to its credit. Many of them don't remember why they're called Hope. Of the ones with a naming story, at least two are apocryphal, New Mexico and Alaska, several are named for people, some are assumed to be named as an aspiration for success, and at least two are named for foundrys and mills, with no recollection of the origin of the business names. Several are ghost towns and at least one is haunted.

Hope, Alaska, being a wild-west frontier town, has much of the charm of Hope, New Mexico. The town is located on the Turnagain Arm of Kenai Peninsula. Unlike many Alaskan towns, you can get there by road, the Hope Highway off the Seward Highway. It's never been big, and has about two hundred residents these days. It arose during the 1898 gold rush, and, according to legend, was named for Percy Hope, the youngest member of a group of gold seekers from Seattle. In 1918 the Cordova Daily Times, Cordova, Alaska, says,"Percy Hope, after whom the town of Hope, to the westward, was called, spent the day with Cordova friends. "

Percy Hope shows up in news accounts at that time, in Seattle, Alaska, and Canada. They can't all be the same person. Seattle's Percy became chief deputy assessor. The one in Canada seems to have run a store. And one was a well known native American, with extensive biography as a political activist. None of his biographers credit him as the namesake of Hope.

The Seattle Percy Hope shows up in the city directory. In 1903 he was a clerk. By 1922 he was the deputy county assessor, and later became chief deputy assessor. This Percy Lee Hope was born in Kentucky in 1874, was married to May Cathie, had two children, and died in Seattle, 1931.

A Percy L. Hope shows up in Douglas Alaska in the 1903 paper, expecting to be divorced from Reinia Hope of Sitka in the next term of court in Juneau. Newspapers record a Percy Hope of Dawson, Yukon, as being a Mormon Elder. These could be the same person but seem distinct from Seattle Percy.

In 1902 the Daily Advertiser of Vancouver, BC, reports that Percy Hope of the North American Transportation and Trading Company, with Pacific Coast headquarters in Seattle, brings news of the mining operations in the area.

Hope, Alsaska is small but enjoys a local fame because of its beauty, accessibility, and reputation as a tourist destination.

Its namesake may well be Percy Hope, one of them, if there was more than one.

Hope, Arizona, is a dot in the desert near California, and its name is reputed to be an aspiration for a business boom.

Hope Arkansas, was named for Hope Loughborough, daughter of a railroad executive in 1873.

Hope, Idaho, founded in 1882, platted in 1896 and incorporated in 1903 was named for Dr. Hope, "a wise and kindly man," the veterinarian who looked after the horses involved in construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The town is famous for the Hope Hotel, which hosted luminaries like Bing Crosby, J. P. Morgan, Gary Cooper, and even Teddy Roosevelt.

Hope, Illinois, in Vermillion County, is famous as the birthplace of Mark Van Doren, and little else, apparently.

Hope, Indiana started out in 1834 as Goshen, but changed to Hope because there was already a Goshen in Indiana. The name seems to have represented the optimistic spirit of its Moravian pioneer settlers.

Hope, Kansas was started in 1871 by a group of 40 peope led by Newell Thurstin who named it for his deceased son, Hope Thurstin (according to popular legend). David Eisenhower lived nearby.

Hope, Kentucky started in 1890 and local legend avers its name came from the first postmaster who had several names rejected by the Postmaster General, finally submitting "Hope" in hopes it would be accepted.

Hope Lousiana was established in 1882 and may have been named for the nearby Good Hope Plantation, a local historical site. How the plantation came by that name is not part of the legend.

Hope, Maine was settled in 1782 as Barrettstown, after the nearby Barretstown Plantation. It became Hope in 1804, and its origin legend says the name came from the Hope family of England, which was friendly to the colonies. Friendly, in this usage probably means financial assistance of some sort, perhaps trade.

Hope, Maryland may not exist, or maybe its someplace along Hope Road. More research is needed.

Hope, Michigan was incorporated in 1850, as a splinter from Barry Township.

Hope, Minnesota has been a post office since 1916.

Hope, Mississippi is in Neshoba County. Someone may know more about it than that. Perhaps they'll write.

Hope, Missouri was a community post office set up in 1897, closing in 1974. It may have been named as an aspiration for hopefulness.

Hope, New Jersey, was surveyed in 1774, accepted as a community by the Moravian Church, and renamed from Greenland to Hope by drawing lots in 1775. The name allegedly reflects the Moravians' "hope for immortality."

Hope, New York appeared after the electors of the southern district of the Town of Wells voted to separate into a new "Town of Hope," in 1818. We don't know what they hoped for.

Hope, North Dakota was founded in 1881, and named for the wife of E. H. Steel, President of the Red River Land Company.

Hope, Ohio was originally the location of an iron blast furnace called Hope Furnace. We don't know how the furnace was named, but in 1865 it gave its name to a post office, which operated until 1890. Hope remains an unincorporated ghost community in Vinton County, with mostly abandoned buildings, a few residents, and a ghost. The night watchman accidently fell into Hope Furnace over a hundred years ago, and remains as the official haunt. His well-sizzled shade is still seen in Lake Hope State Park.

Hope, Oklahoma is an unincorporated place in Stephens County.

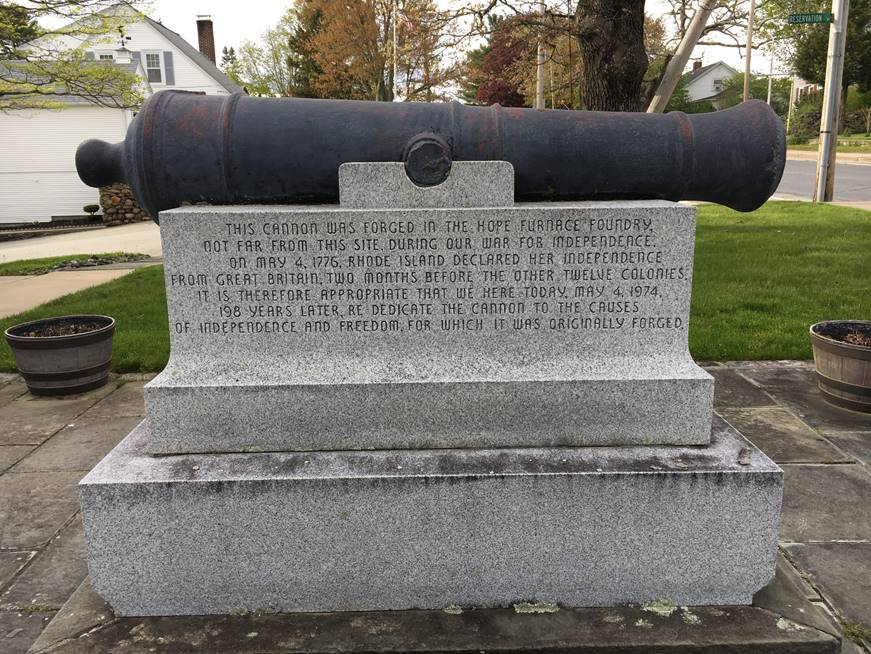

Hope, Rhode Island, like its Ohio sister city, was named for an iron smelting operation called Hope Furnace. The mill produced cannon for the revolutionary war, and by 1806 had given its name to Hope Cotton Factory. It's been known as Hope Village since 1844. By the way, "Hope," is the motto of Rhode Island. Someone ought to look up why.

Hope, Texas in Lavaca County was named for a trading post sometime before the Texas revolution. We don't know what the trading post was hoping for.

Hope, Washington in Pierce County is a real place, but is most prominently featured these days as the fictitious setting for some of the Rambo stories.

Hope Wisconsin is an unincorporated community in Blooming Grove, Dane County.

If America's Hopes were hoping for long-term prosperity, most hoped in vain. If they were hoping to be remembered, they've succeeded.

...

In 1949 the Army took a long, wide swath of the Tularosa Basin north of El Paso for the White Sands Missile Range. They needed a place to park their German assets, men and machines, from Penemunde, and to host weapons testing in a remote, hard-to-observe place. New Mexico's Jornada Del Muerto was inconvenient to get to, flat, and blessed with predictable weather, hot and dry. Some ranchers were displaced, but the ones who weren't found they'd acquired a powerful neighbor. In 1997 the Department of Defense did some reflecting about the educatonal opportunities in those early days.

The publication "School Days" was issued in 1997, including interviews with some of the old timers. Several were from Hope, New Mexico, and we've excerpted their stories below. You can read the entire publication nearby.

Elma Hardin Cain

Elma Lois Hardin was born in Hope, New Mexico, on May 17, 1925. Her parents, Charles W. and Lois Watts Hardin, lived in the Sacramento Mountains. Elma attended school in Hope and Artesia until 1934, when the family moved to the San Andres Mountains. At that point, herparents opted to send her to Loretto Academy in Las Cruces. She graduated from Loretto in 1942. Elma's vivid recollections of life at Loretto Academy provide a strong contrast to experiences related by those who attended the one-room schools out in the ranch communities.

In 1943, after attending Loretto Heights Academy in Denver for a year, Elma married Leonard Cain. They settled on the family ranch, the Buckhom, in the San Andres, where they began their family and raised cattle until 1949, when they moved their ranching operation northeast, to a spot near Amistad.

J. D. Miller

J. D. Miller was born in Hope, New Mexico, on July 26, 1916, to Lealon 0. and Agnes Hardin Miller. He attended school in Hope through the fifth grade, while his father ranched and hauled freight. When J. D. was 10 years old, the family moved to a ranch in Arizona. The rancher's wife was a school teacher and taught J. D. at the ranch until his mother moved into town so he and his sister could attend school. For one year, J. D. and his sister stayed in Deming, New Mexico, with relatives; then they returned to Arizona, where J. D. graduated from eighth grade.

In 1933, when J. D. was 17, his family relocated to the San Andres Mountains. In July of 1938, J. D. married Dorothy Wood. He was awarded the contract to drive the bus for the Ritch School from 1938 to 1940, picking up and dropping off children along a 23-mile route that took roughly two hours to traverse.

Louise Crockett

Louise Crockett was born on September 3, 1912, to Dick and Edna Roach Alexander, in Eunice, New Mexico. As a child, she lived in Eunice, Hope, and Pirion. Louise graduated from high school in the then-thriving farming community of Hope. She married Lloyd Crockett in 1932 and they began a sheep ranching operation near Pirion but moved to a ranch in the Rhodes Canyon area in 1938. Louise and the Crockett children moved from the ranch into town during the school year. The kids attended school in Las Cruces for four years and in Hatch for five years. Finally, the family moved to Hatch.

Cora Cox Fribley

Cora Cox was born May 20, 1904, to George W. and Julia Beach Cox, in Hope, New Mexico. The family moved to the San Andres Mountains around 1916.

There was no school near the Cox Ranch, so the family also purchased a house in Tularosa in order to have a place for Cora and her brothers and sisters to live with their mother while they were attending school. Cora remembers being the best seamstress in her Home Economics class and how they had a difficult time with the cooking exercises because there was no food provided by the school.

Interview with Cora Cox Fribley

My dad was George W. Cox, and I'm sure he was born in Liberty Hill, Texas. He was a rancher's son, and I guess they came from Texas looking for places to live. They had a cattle ranch about 30 miles from Hope. My oldest brother and sister were born in Texas. She was just an infant when they came and I wasn't here yet. They got me later.

Well, I guess they had heard about the range, how the grazing was, and it was good that year. My dad went out and thought it was wonderful. So he sold the place, and he and his brother moved to the San Andres. I think it must've been about 1914 or '15. We were out there during World War I.

He bought this place right here in Tularosa after he sold the homestead, so we kids could go to school. It was more than 60 miles; took all day just about. Yeah, get in the wagon and rootie toot, here we come! Well, we finally moved for school and just stayed in town. Those other people didn't move to school. I don't know what they did. We'd be here all winter, the school year. I had gone to school before we came to Tularosa, 'cause they had a little country school. Little young girls would go out there and teach for nothing— $30 a month— and live in the house of some of the people. Yes they did. I'm sure they did, 'cause they had this one-room schoolhouse. I never thought that would be interesting; might be interesting, but wouldn't be very funny.

I was a basketball player for Tularosa about seventh grade and a Girl Scout. There was three girls played basketball. They were short of girls when they got me. The Bookout girls were the star players. We played Capitan and Carrizozo, but we didn't play Alamogordo because they were too high-toned for us. They were citified. We're the country kids. I was 13, I guess. It was probably around 1916 or '17. I remember Mr. Clayton was our referee. One day I played mean and he told me I'd have to sit on the bench if I did it again. I didn't do it anymore. Yeah, he thought I was a little mean. I hit that ol' girl under her chin, I didn't bite her tongue, she did it. In those days they had a running center, and I was runnin center.

Interview with Louise Crockett

I was born in Eunice, New Mexico, in 1912. When I was five, we came to Hope to send us kids to school. It's a pretty nice town then. Many people there; the best fruit orchards and vegetables in the world. We didn't go much of any place, except to school and church; school plays and programs and things like that.

We were married in '32. We went to ranch out on the San Andres Mountains in about '38, I guess. Then I lived in Las Cruces; sent 'em to school four years. I never thought about lockin the door then. And then I lived in Hatch for five years and sent 'em to school. I guess Sonny was eight when we moved to Hatch, about '45; he was born in '37.

Interview with Elma Hardin Cain

I went to school in Hope [New Mexico] a couple years, and I went to school in Artesia a couple years. Then I went to Las Cruces and finished high school at Loretto Academy. I was 9 when I went to Loretto.

I don't remember how big Hope School was. There was probably 20 in my class. I don't remember, but Hope was a pretty good size town at that time. I stayed with my grandfather and grandmother, my daddy's parents, and went to school. When they moved to the San Andres Mountains, we— Mother and I— moved to Artesia. I could have gone to school at Ritch, but the folks didn't want me to. That's when they put me in boarding school at Loretto, from '34 or '35 through '42.

But sometimes you get a better education in a country school than you do in a public school. Even though there's maybe one or two teachers to a big bunch, they get more individual attention than you would in a bigger public school.

They took me down and left me. I stayed, but I didn't like it. I don't remember a lot of conversation, other than I had heard that they were going to take me, and that the nuns—you know, I'd heard that if you weren't nice they'd put you in the basement. I'd heard scare stories and, of course, I cried and cried for two weeks. The nuns wrote Mother and told her that she'd better come down and see about me. Mother came down, she and Daddy, and he told me, "You're gonna stay. You might as well get over it. If you don't quit and settle down, we won't let you come home Thanksgiving, Christmas, or Easter; we'll just leave you here." Well, it wasn't long 'til I shaped up. When I came home Thanksgiving, I was so lonesome, I was ready to go back. I had adjusted. There was no question whether I would go back to Cruces from year, to year, to year. That was understood.

School started after Labor Day and we got to come home at Thanksgiving. I usually rode the bus to T or C [Truth or Consequences, New Mexico] and the folks would pick me up. Then they'd take me to T or C and I'd ride it back to Cruces. Same way at Christmas, and the same way Easter. It wasn't too awful far, probably an hour and a half or two hours. It was just riding the bus; it wasn't too bad.

We were off at Thanksgiving for two or three days, and Christmas, about a week off at Christmas. Then Easter, usually we'd get off. Get to go home on Thursday and come back on Easter Monday. Then go home at the end of school and go back to school in September.

When I first went to Loretto, there was 72 boarders from the first grade up to high school. A lot of those—well, not a lot, but maybe 10 or 12, maybe more—were out of Old Mexico, and they couldn't speak a word of English. Some of 'em young, some of 'em older. We had two dormitories. We had a little girls' dorm and big girls' dorm; the high school girls and the little kids.

Loretto Academy was at the end of Main Street. The front of the building was big; the middle was the administrative part of the school. To the west were the dormitories upstairs and the classrooms and things downstairs. To the east, the chapel was upstairs and the nuns' quarters were there. On the bottom floor was the cafeteria and the kitchen and different things like that. It was sort of in an L shape, more or less.

They were all nuns, Sisters of Loretto. I never had a lay teacher. The Music teacher, History teacher, English teacher, they were all nuns.

It was very rigid. We got up about six o'clock every morning. You could not talk at all to, you know, visit with the other kids and all—it was in silence. We went to mass; we went to church every morning. You'd get dressed and brush your teeth and wash your face and comb your hair and you'd go to church. From church you would go directly down to the—the refectory is what we called it, not cafeteria— the refectory. And we'd all stand behind our chairs and they'd say grace and ring a little bell and we could sit down. We could visit and talk when we ate breakfast. Whenever everybody was fairly well through, they'd ring the bell and you'd stand up and return thanks, and go in silence up to make your bed. Then you'd come back down at 8 o'clock.

They'd ring a bell and you would go to study hall. You would have study hall and your classes the rest of the morning. Then at noon you'd get in line and you go to the refectory and the same routine. Then you have recreation until 1 o'clock, after you'd had dinner, which wouldn't usually be very long. Then you'd have classes in the afternoon. At about 3 or 3:30, you be out; school would be over and you'd have recreation 'til about 4:30 or 5 o'clock.

We had tennis courts, and you could skate, or you could listen to the radio, if the radio was working, or you could just read, or whatever you could find to do. Then you'd have study hall from 4:30 'til about 5:30, somewhere around there. Then we'd go and eat supper, and at 8 o'clock the little girls had to go up to bed.

When I got to be a freshman, I was a big girl, and then we got to stay up 'til 9. It was the same routine over and over every day, except Saturday. Saturday, if you were lucky, they might let you sleep late if you were a big girl. A little girl, you didn't get to sleep late; you got up and went to church on Saturday. Whenever you got to be a big girl, on Saturday you'd get to sleep late maybe; but Sunday you'd go to church and then they'd have study hall from 11 'til 12 so you could write letters home. And you write your letter and the nuns would correct it and then you'd have to rewrite it. They read all of your mail, coming in and going out.

There weren't any chores to do, other than you had to mend your clothes. Sometimes on Saturday they'd take us up to the wardrobe. If you had a button off or something like that, they'd show you how to sew it on. If they wanted to teach you how to darn, if you didn't have a sock that had a hole in it, Sister Arcela would cut a hole in the sock, so you could darn it. Darning, you put an egg, a darning egg, in the sock and you learn to close that hole up. You went one way all the way, and then you went and wove in and out the other way.

And they taught you manners. If you were a lower classman and an eighth grader came by, you had to open the door for the eighth grader. If you were a sixth grader, you had to show that eighth grader respect.

It was always the same, always the same discipline. It never changed.The bigger girls had a little more leniency, but not a lot. As far as talking and keeping silent, going to eat, and things like that, they were all the same. They just wanted you to go in silence. That was teaching you that you had to be quiet.

And then when I got older, I worked for part of my tuition. I waited tables in the refectory and I cleaned the music rooms whenever I could. There was some that had chores like that. The biggest end of the girls didn't have any; they didn't have to work, but I did. I've often wondered what tuition might have been, but I don't know. I do know that Daddy, several times, brought a beef down—killed a beef and brought it down for part of my tuition.

It was a Catholic school, and naturally they taught Catholicism—you know, religion. Everybody took it. It was very strict. But if you failed a test, they would have you study and they'd give it to you again. They'd give you an opportunity to pass. We had one teacher that would give you the question and the answer. Say, she'd give you 50 questions and answers, and she'd pick maybe 10 or 15 out of that. Alright, she wanted it word for word, and dot for dot. You had to have not only the question answered correctly; she wanted your penmanship and your spelling and your punctuation— everything— right. Everything she marked off, because she gave you the whole thing, and you were to learn it. She was very meticulous in that, and you learned pretty quick that she wasn't going to put up with sloppiness and not doing what she wanted.

We had a priest that lived there. I think he was just the father that held the church services. We had mass every morning at the school at the same time, early every morning. We had a sister — called her Mother Superior— I'm sure that she was the one that took care of the business, 'cause she didn't teach.

I don't remember any of the nuns leaving. As you got older, you got different teachers, but they had been there for years. The one nun that I remember, that stayed in the little girls' dormitory, she was there forever. The dormitories, they were all in one room, one big room. They were all, in the little girls' dorm, all different ages. In the big girls dorm, you see, were the high-school kids, freshmen up to seniors. I don't remember how many beds were in there. The nun's bed had curtains around it. Usually there were two nuns that slept in the little girls' dorm. I'd say there were maybe 40 beds in there. I don't really know, but they were just rows and rows with just a little space in between.

In the little girls' dorm we had a washstand, and we kept our toothbrushes and hair brushes and things like that in there. Each one had their own washstand. When you got to be in the big girls' dorm, you had a washstand, but then you had an alcove. They had a room where there was a little alcove-type thing that had three walls and a curtain in front. You had a little chest of drawers in there and you kept your little personal things in there. You could hang some of your clothes in there, but the little girls' things were all up in the wardrobe room. You wore a uniform, a navy-blue uniform with a big, white collar. I have my white collar from whenever I got out of school. I had it autographed and I kept it. But I didn't keep a uniform; I didn't want a uniform. But you know, you get used to it. It's just, sort of like the Army, I imagine.

Mother used to send me a birthday cake, and it would be packed in popcorn; an angel food cake with seven-minute icing, and she'd pack it in popcorn. When that package would come, well, we kids would sneak and get on what we called the devil steps— they were steps saved for visitors. They were hardwood steps. We'd get there and eat our cake and popcorn. We'd crawl out of the dorm; we got in trouble several times. We'd have to clean those steps—wax them and polish them and clean them up. Then lots of times we had to write "I will not do" whatever it was "again" maybe 500 times.

They did have one girl, she called the sisters "You old devil. El Diablo, El Diablo." They washed her mouth out with soap several times, but ..

There wasn't a lot of ruckus, 'cause someone was there watching all the time. We were chaperoned even when we went to town. There'd be two or three nuns that would go with us to town. We were just, well, at the end of the street. It might have been six or eight blocks.

The meals were very well prepared. The only thing, I thought we got too much parsnips; I never did like parsnips. But we'd have cream of wheat for breakfast of a morning, and if we didn't eat it all, they'd fry it at night and serve it with syrup for our evening meal. I liked the cream of wheat of a morning, but I didn't like that of an evening. We'd have prunes for breakfast, and I didn't mind those. If there were prunes left, we'd have prune whip at night for dessert, and that was good. I didn't mind that too much. Those are about the only things that stick in my mind. The meals weren't bad. They had people in the kitchen that weren't nuns, and I'm sure they were bound to come from town, but I don't remember who they were.

Mother and Dad, they could come and see us. They would come and take us out in town and things like that, but we couldn't go out in town just as a group. When I got to be older, there was one girl that was in school, and I got to go home with her over a weekend.

You got a good education, as far as learning. We took Music. You had Spanish and Latin and Math, different kinds of Math, and Shorthand and History and English, and they had the Business classes then, too — Bookkeeping, Shorthand, Typing.

Its all right, but I would never send my kids. I don't think so. No, uh-uh, because I think you miss so much with your parents and with other things, other activities and things. I never saw Leonard play football. I never saw a football game, a high-school football game, or a basketball game, other than what we played there in the convent. You miss things like that.

When I first went, there were 72 students, as I remember. When I graduated, there were 42. They decreased and decreased. But now, that was boarders. They did have some Catholics that came in as day students, you know. I don't remember how many there were. A lot of them didn't come from Old Mexico anymore. Maybe it got too expensive for them to come there; I don't know. I know when I graduated, there was 3 that lived there in 'Cruces, and there was 10 of us that graduated, so there was 7 of us that were boarders, the summer, May of '42, I graduated.

When I graduated from high school, that fall, my grandmother and mother took me to Denver to school. The college in Denver was also a girls' school associated with the Sisters of Loretto. I got a scholarship to go to Loretto Heights, and I was Valedictorian of my class. Now we weren't restricted to go to bed at a certain time and we could go to Denver and, you know, out. A group of us would go out. The only requirement when we left the Loretto Heights Academy, we were supposed to have a dress on and gloves and a hat and high-heel shoes and hose; we were supposed to be representatives of the school and act accordingly. Of course, lots of times, by the time we got to Denver in the taxi, we had shed a lot of hats and gloves and various things! I stayed up there and I came home at Christmastime, and I rode the train back with Leonard, back to Denver. We got married the following summer.

The space race did not begin in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik, but in 1954 when both America and the USSR announced satellite launches as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) activities. This region of the collage is generally identified by that term, although each illustrated object is probably a specific, as yet unidentified, event.

The IGY was a major force in scientific activity in the late 1950s, and does not seem to be separately celebrated by the collage.