“St. James Infirmary” captivates a select audience for reasons hard to articulate. A few outstanding researchers have already looked into the matter, and all I can add is my own fascination. Josh White introduced me to the song as a college sophomore, a resonant age for its fusion of regret and fatalism.

Many commentators, perhaps all listeners, are intrigued by the line, or some version of it: “She can look this wide world over, and never find as sweet a man as me.”

Prior to that the singer has been lamenting a lost lover; everything afterward is a celebration of personal mortality. This fulcrum line balances the emotional response, and the stories of how it got into the song are as fascinating, and inconclusive, as the tune’s origin myths.

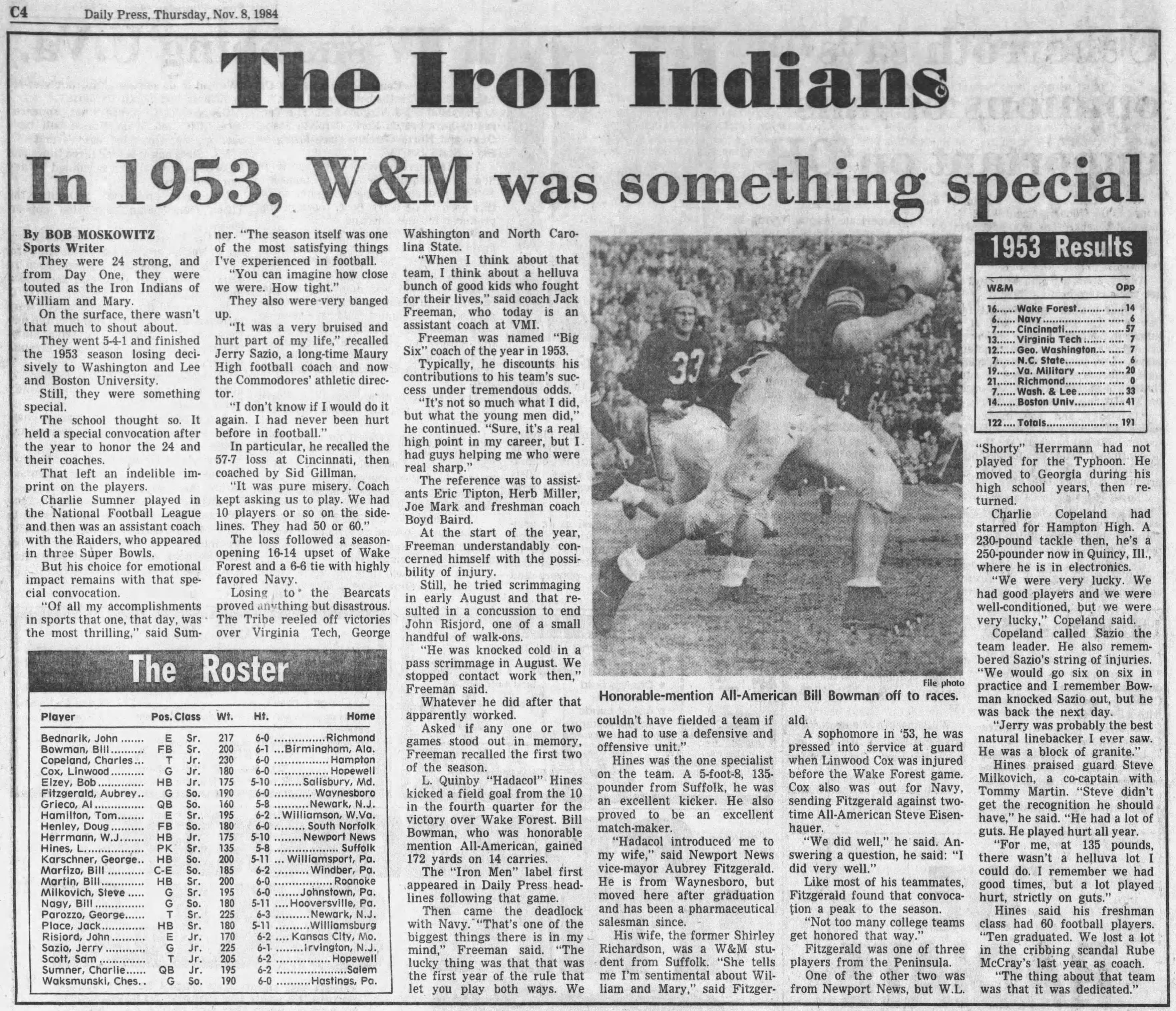

The song seems to have started out in 18th century England as a repine of social disease, and migrated to America where it went south, as “Those Gambler’s Blues,” and west, as “The Streets of Laredo.” The former appears in “The American Songbag,” a collection of folk songs, by rambler, poet, historian, Carl Sandburg, published in 1927. Gambler's Blues was apparently circulating widely on the entertainment circuit by that time. Fess Williams recorded it in 1927.

Then, in 1928 Louis Armstrong took charge of the song's legacy with a recording that has become its gold-standard reference. He is the personal National Bureau of Standards for the Old Joe's Bar Room tale.

St. James is a common enough place name in both England and America. Multiple locations for the “real” St. James have been proposed, including a hospital in London that closed two hundred years before the song's earliest speculated origin. Historians have also dug up a work house in Piccadilly with better temporal coordinates, and a Methodist Church in New Orleans. If your curiosity is itching with questions, I suggest the following sources of relief.

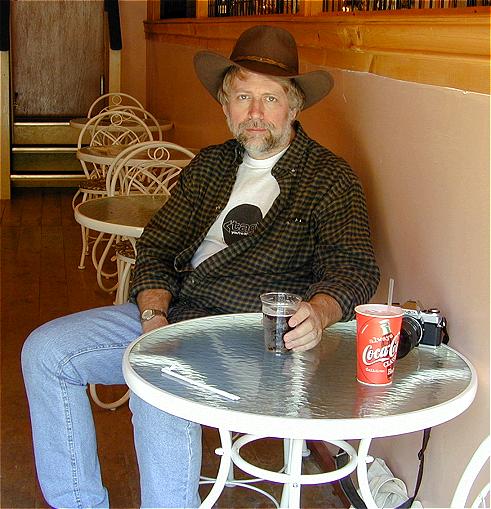

A commendably energetic, thorough, and informed researcher is Robert W. Harwood, who is responsible for the quote under the picture above. He maintains a blog, and has written a book, now in its second edition. He's the A-level authority.

Rob Walker has also researched and written extensively about “St. James Infirmary.” Unfortunately for us, Rob has discontinued his blog, but you can still find his book, "Letters from New Orleans," on the Internet, and there are still a few fragments of his postings available, plus a recording (see nearby).

Brian Cryer, Internet polymath, devotes a section of blog real estate to the St James question on his "Everything Explained" blog. Additionally, Peter Patnaik has posted a marvelous collection of audio files on his site, "Where you been so long?"

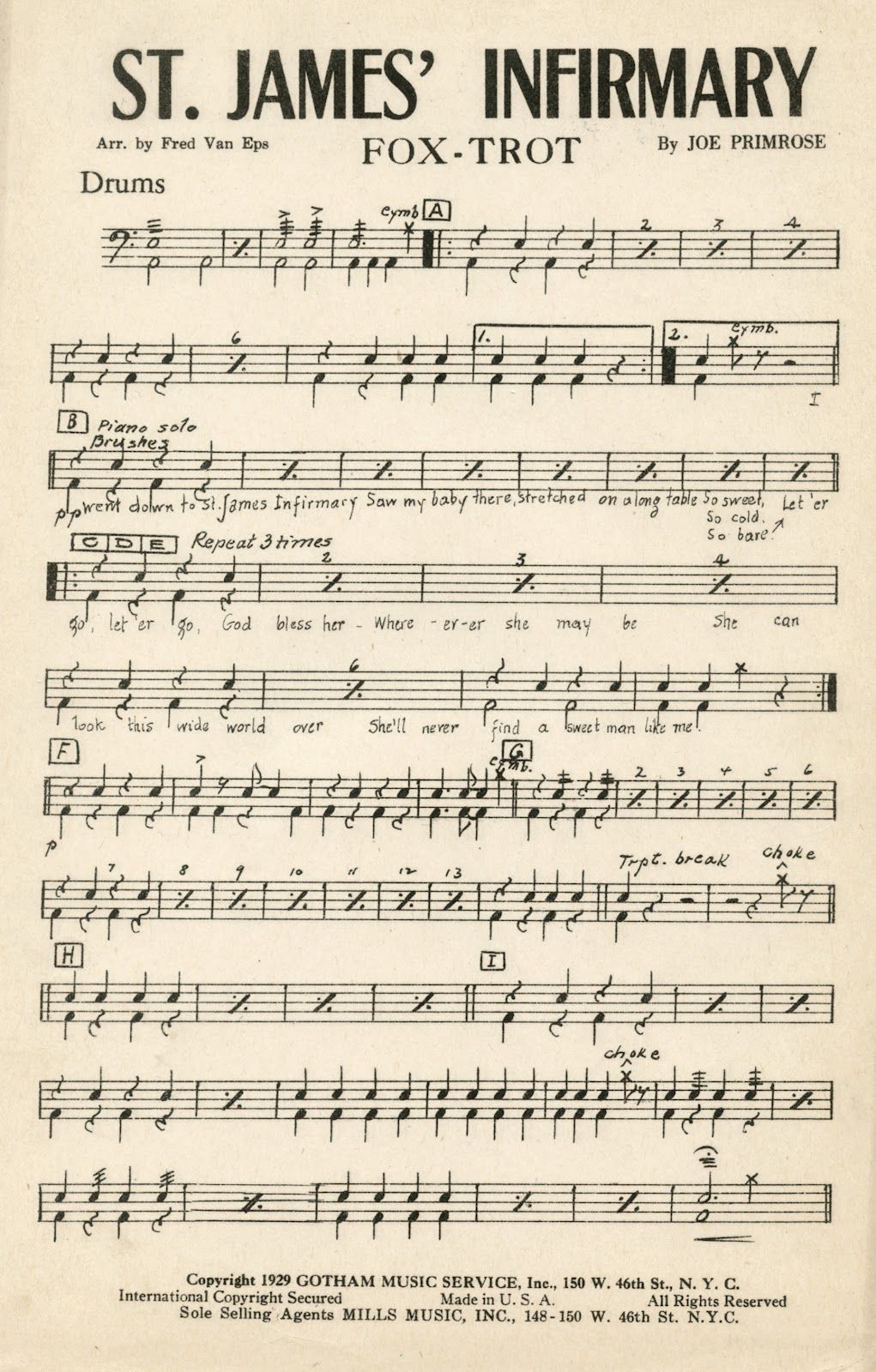

Below is a version of St. James Infirmary done by Dick Robertson in 1929, or 1930. It incorporates an amalgam of various versions, starting with the complete Armstrong lyric, then incorporating changes made by Mills (aka Primrose) in his copyrighted version, and concludes with a verse apparently original with Robertson.

Gallimaufry's Attic is a place to store things for rediscovery. Below we sprinkle a few observations among playback links to different, sometimes surprising, artists who have recorded St James Infirmary. Many recordings are from YouTube, so there may be advertisements. Be patient. People you don’t know are trying to give you free stuff.

Josh White’s life is the history of black American music finding a white audience, of folk music and the American left, and of a man who remade himself time and time again, fighting discrimination, stereotypes, and his own personal demons to become one of the world’s most successful black entertainers, then maintaining himself in that position through four decades. Josh was hailed at various times as king of the blues singers, king of the folksingers, king of the political singers, pioneering black sex symbol, "Presidential Minstrel" to the Roosevelt White House, and king of Cafe Society. Here he is doing two different versions of St. James Infirmary. For many people, his was the version they heard first, and appreciate most.

Louis Armstrong left New Orleans in 1922, at age 22, to join his former bandleader, father figure, King Joe Oliver in Chicago. During the twenties he left Oliver and formed his own seminal band, The Hot Five, including his future wife Lil Hardin, Clarinetist Johnny Dodds, trombonist Kid Ory, and banjo player Johnny St. Cyr. The group expanded into the Hot Seven with the addition of Dodd’s younger brother, drummer Baby Dodds, and tuba player Pete Briggs. There were other musicians as well, from time to time. Armstrong was recognized for his virtuosity and creativity, and was the last New Orleans trumpeter recognized as King. He recorded St. James Infirmary many times. Here is a session from his All Star band in the 1960s(left top), and from his Savoy Ballroom Five (his first recording of the number), from 1928.

An amazing variety of scholarship, speculation and artistic interest advances on St. James Infirmary, both the song and the institution. The Wellcome Library, is a private collection of historical artifacts and information on the history of medicine. Surprisingly, the name is not a cutesy play on wellness and welcome, but the name of the benefactor, Henry Wellcome, who inspired and founded the effort. Their blog assays the origins of the song because of its apparent roots in venereal disease. They give us a Eurocentric version of the origin story, disregarding the apparent anachronism of their St. James Infirmary nominee being torn down centuries before the the song became known. They also point us to a BBC documentary.

At the right, an a cappella choir called the JUUL Tones, who sing for the First Unitarian Universalist Church of San Diego, perform the SATB (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) arrangement done by a Cal Tech math, music graduate named Everett Howe.

King Oliver is said to have started as a trombonist, and from about 1907 he played in brass bands, dance bands, and in various small groups in New Orleans bars and cabarets. In 1918 he moved to Chicago (at which time he may have acquired his nickname, a royalty of New Orleans trumpet/cornet players going back through Freddie Keppard to the fabled Buddy Bolden), and in 1920 he began to lead his own band. In 1922 he started an engagement in Chicago at Lincoln Gardens, as King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band. A month later he hired the 22-year-old Louis Armstrong as second cornetist. With two cornets (Oliver and Armstrong), clarinet (Johnny Dodds), trombone (Honore Dutrey), piano (Lil Hardin), drums (Baby Dodds), and double bass and banjo (Bill Johnson), Oliver began recording in April 1923. Many young, white jazz musicians heard him, either on recordings or live at Lincoln Gardens.

In the late 1930s, in ill health but needing money, he made some recordings with an orchestra that included New Orleans trumpeter, Henry “Red” Allen. King Oliver’s orchestra, with Red Allen, can be heard on the left, while another version by Red Allen, made in 1964, is on the right.

The trumpet work on the Oliver recording is generally assumed to be mostly Red Allen as Oliver was in poor health at the time. The growl phrases are probably Bubber Miley. The Red Allen recording was made two years before his death in 1964, and includes some vintage trumpet phrasing, plus some more modern energy and presence.

Eddie Condon (1905-1973) and Jack Teagarden (1905-1964) were among the young white boys enraptured by the music of black bands coming mostly out of New Orleans. They were not part of the famed Austin High School gang, but played recording and band dates with them, and young Bix Beiderbecke of Davenport, Iowa. On the left is a band of Jack Teagarden’s and on the right, one headed by Eddie Condon.

Teagarden recorded this in 1954, shortly after leaving Louis Armstrong’s All Stars. His laconic voice and trombone technique give us the feel of a New Orleans funeral, although Teagarden was a Texas boy. Eddie Condon was known more for organizing great recording sessions than for his playing, and he brings some great talent together here. The Armstrong-like trumpet is Wild Bill Davidson, and Vic Dickenson gives us a very dirty sounding trombone.

Sidney Bechet, at right, (1897-1959) was a child prodigy in New Orleans. He was such good clarinet player that, in his youth, he was featured by some of the top bands in the city. Bechet's style of playing clarinet and soprano sax dominated many of the bands that he was in. He played lead parts that were usually reserved for trumpets, and was a master of improvisation. In 1917 he moved to Chicago. In 1919 he was playing with Will Marion Cook's Syncopated Orchestra, and with Louis Mitchell's Jazz Kings in Europe. While overseas he bought a soprano sax and from then on it was his main instrument.

The Bechet recording is probably the one on Climax records in 1945 with George Foster on Bass, Wild Bill Davison on cornet, Fred Moore on drums and vocal, Art Hodes on piano, and Bechet playing his flaming soprano saxophone. The mix with the old silent movie, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” has nothing to do with Bechet.

Allen Toussaint (1938-2015), was a New Orleans R&B piano impressario and composer who brought the New Orleans sound to his work. This recording is a rare instrumental version of St. James Infirmary, but the lyrics are not missed.

It is startling to find St. James Infirmary sprouting everywhere on the Internet. People spend significant portions of their lives communicating an aesthetic infatuation, as if trying to touch an inner hot-wire of spiritual power. Catch up with Ricky Riccardi, author of “What a Wonderful World," and self-confessed “Louis Armstrong freak,” as he tells us about the importance of St. James Infirmary. There may be a direct link to gravity waves, here. In case you don’t investigate his blog, you've got to listen to this Armstrong version of St. James, which he discusses.

Much in the blogosphere, as we semi-professionals somberly call it, is--now, what’s a compact word for superficial flotsam and jetsam? But then, scrummed in there amongst the variations of, “God Almighty,” "Awesome,” “Like--cool man,” and smugly righteous subnumaries, we come across something like this (upper right). Here’s a former English teacher, turned data base analyst, confessing a spiritual connection to this confounded song. If you’re wondering what makes St. James Infirmary so interesting, check out John Simpson’s blog which is interesting for much the same reasons. What may appear as quirkiness, to some, will be recognized as honesty. Again, if you’re too rushed to check out the blog, at least listen to his song selections.

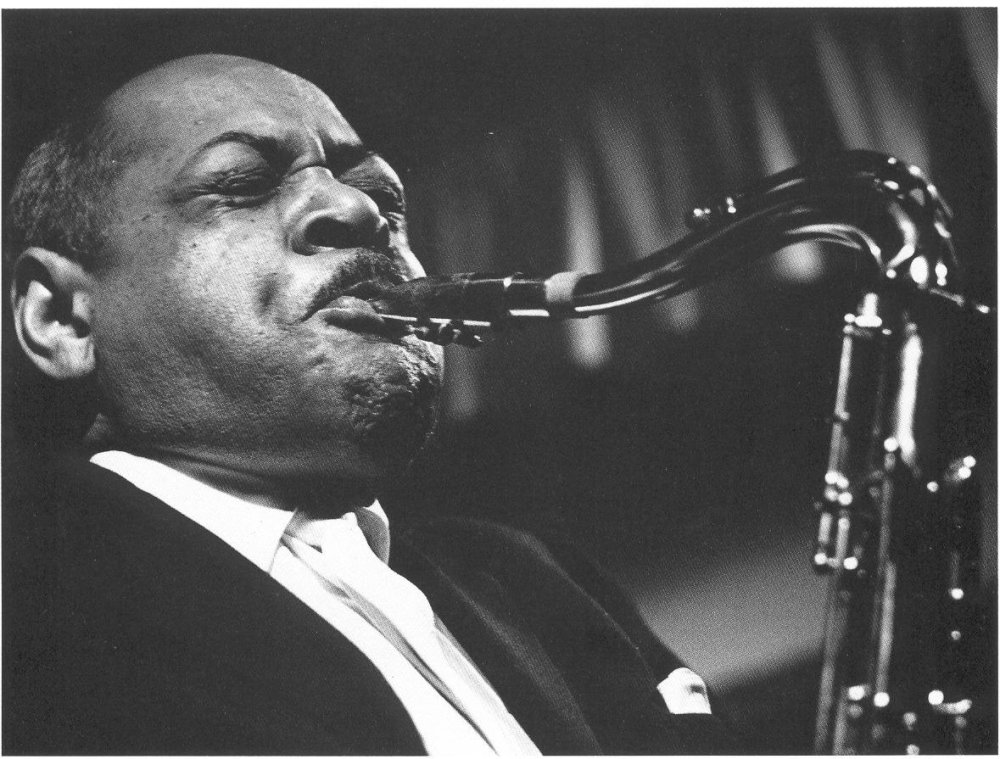

Coleman Hawkins, 1904-1969, is credited with making the tenor saxophone a true jazz instrument. He joined the Fletcher Henderson orchestra in New York and was influenced by its trumpet player, Louis Armstrong. He and another Henderson trumpet player, Henry Allen, made a series of recordings, before Hawkins left the band and toured Europe. On this recording, made in 1945, he is joined by his old sideman, Red Allen, who does the vocal, and Hawkins gives the old tune a new dimension.

Duke Ellington, 1899-1974, was a chromatic artist in tonal medium. His compositions and recordings define the pinnacle of band music in terms of technique, intellect, and innovation. This recording was done in 1930, under the band name of “Harlem Hot Chocolates,” featuring Cootie Williams on trumpet, Tricky Sam Nanton on trombone, Johnny Hodges on saxophone, and Barney Bigard on clarinet. The vocal is by Irving Mills. The similarity to Calloway is striking, although the integrity of the Ellington piece seems higher.

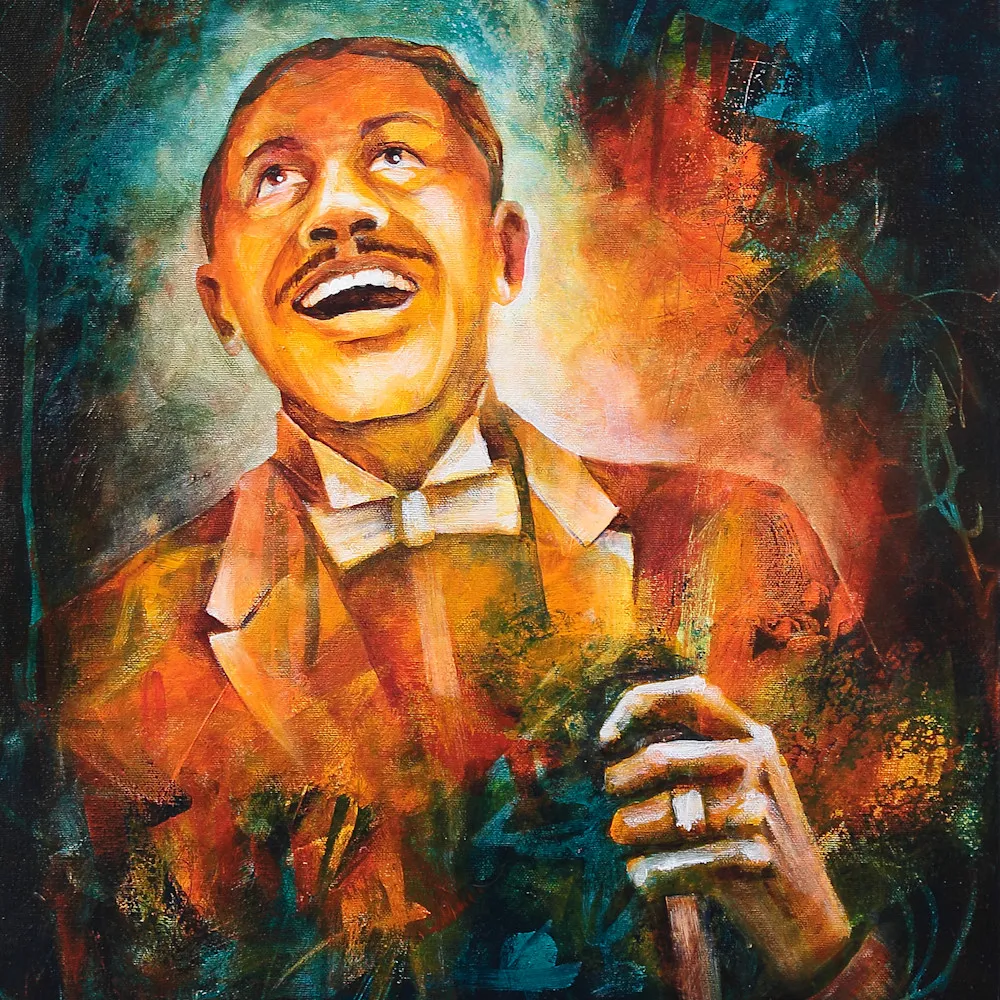

Cab Calloway, 1907-1994, was a regular at the old Cotton Club in New York, where another great band leader, Duke Ellington also camped out. His soaring, winding voice gives the song a sound some prefer to the grittier renditions of Armstrong. Calloway did a version for the 1933 animated film, Snow White, but we don't know if this is it.

The Preservation Hall was opened in 1961 as a cultural preservation movement. The eponymous jazz band was formed by Kid Thomas in 1963, and personnel varies. This seems to be the band’s 1966 version of St. James Infirmary. The lyrics borrow extensively from the Gambler’s Blues. Personnel are: Lester Caliste, William Brown on bass horn, Willie Humphrey on clarinet, Allan Jaffe on tuba and bass horn, Andrew Jefferson on snare drum, De De Pierce on vocals and cornet, Edmond Foucher, and Emanuel Sayles on banjo.

Here (upper right) is a rendition of the tune by Jim James, 1978-present, performing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in 2012. There is another Jim James version with more punch and weirder lyrics, but it was unavailable.

Dr. John, 1940-present, gives us a typical John performance with lot’s of funk and junk and ad libbing. He uses the traditional lyrics as a point of departure, from which he is mostly departed, and the tune is uniquely John, also. Plenty of New Orleans in this number.

James Booker (1939-1983) was a New Orleans piano player who combined R&B with classical jazz standards. Dr. John once called him, “The best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius New Orleans has ever produced.” He was also called “the black Liberace.” For sheer genius and flamboyance, this keyboard treatment stands alone. If you don’t want a brass band at your funeral, this would be a good fall back. The lyrics, like his playing, are conventional and innovative at the same time. Like some others, he leaves off his funeral instructions, departing from the song's origins.

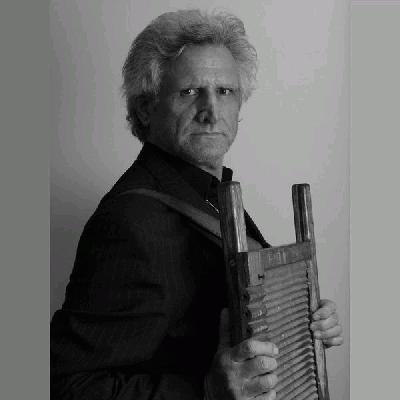

“Washboard” Leo Thomas, born and raised in New Orleans, is the inventor of the Electric Washboard. He has played everything from classical jazz to rock on his famous washboard, all around the world for over 40 years. The New York Times called him “the Jimi Hendrix of the Washboard.” He has played with David Allen Coe, Earl Scruggs, Fingers Taylor (Jimmy Buffet’s piano player), John Prine, David Greely, and Willie Nelson. Washboard Leo does St. James Infirmary as a novelty number, inventing a different story line in which St. James Infirmary is not even mentioned, and the emphasis is on his own funeral.

Jerry Reed(1937-2008) was a country music singer, songwriter, and actor, who specialized in a variety of novelty numbers. Like many people known for their humor, he was a sincere, almost serious man, and he gives us the first part of the traditional lyrics with a mixture of weight and levity, eschewing the instructions for his funeral at the end.

The two recordings give us different halves of the emotional experience of balancing around the “Never find as sweet a man as me,” fulcrum.

Artie Shaw (1910-2004) was a clarinetist, composer, bandleader, actor and author. After World War II he drifted out of the music business. This recording was made by his last pre-war band, with Kansas City hornman Hot Lips Page doing the vocal, and some searing trumpet work. His lyrics balance around the “sweet man like me” phrase, but end after the twenty-dollar-gold-piece, before the pall bearers, singers, and jazz band, probably a time limitation on the recording.

Trombone Shorty (Troy Andrews, 1986-present) is a multi instrumentalist musician from New Orleans. He took up the trombone at age four, became a bandleader at age six, and has toured with his own band since 2009. This performance is from a White House appearance in 2012. He gives us the front of the lyrics, including the fulcrum phrase, followed by some Cab-Calloway-like Hi-De-Ho riffs, and inspired trombone virtuosity.

Django Reinhardt (1910-1953) is considered one of the greatest of all guitar players. He was a Belgian-born, French gypsy (Romani), who recorded extensively with the Quintette du Hot Club de France. He is often remembered for his collaborations with violinist Stephane Grapelli. This is a typical Django performance, with surprisingly competent clarinet accompaniment, and, typical of Reinhardt, no lyrics.

Doc Watson (1923-2012) was a guitarist, songwriter and singer of bluegrass, folk, country, blues and gospel music. He was also a music historian and often worked some interesting commentary into his numbers. He gives us some variations on different entries to the song, falling into a unique, very personal fusion of anguish and picking. His interpretation also stays with the blues of personal loss and never gets to the bravado of funeral arrangements.

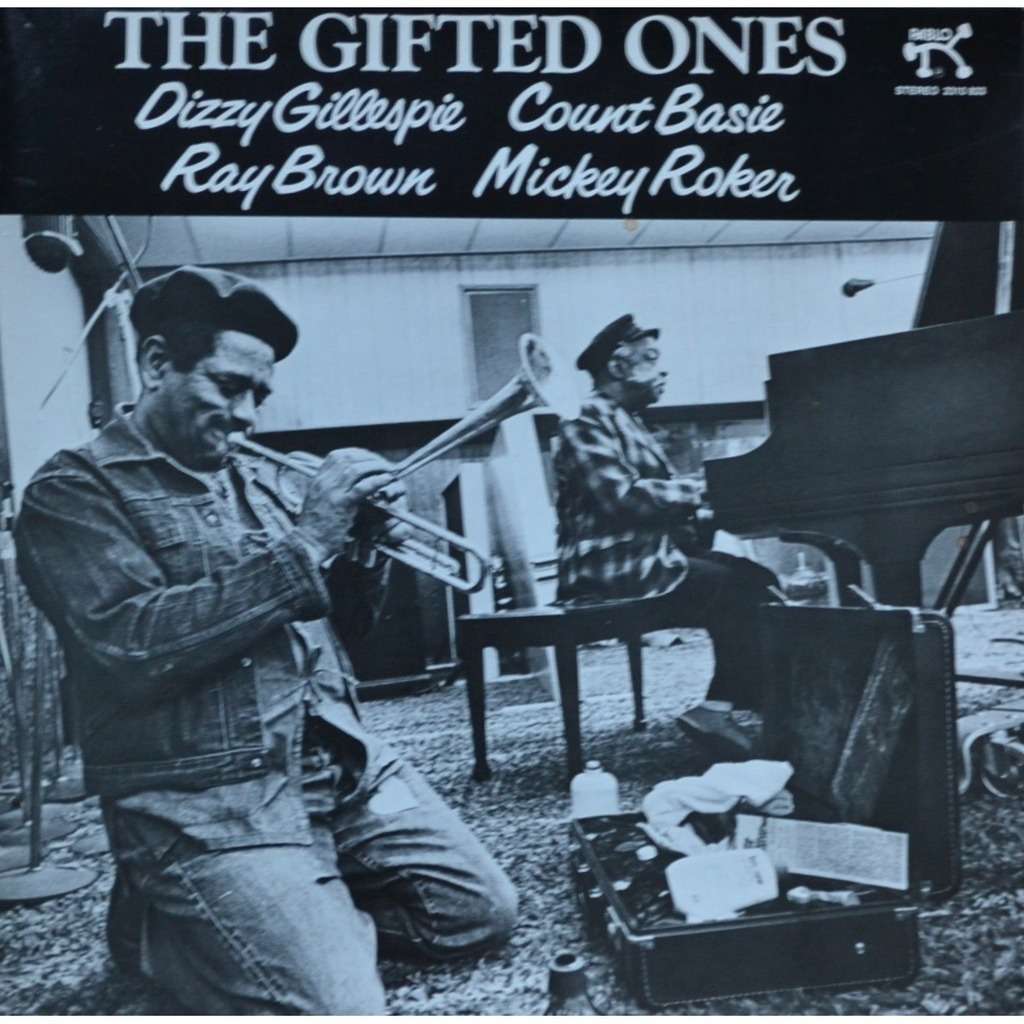

Dizzy Gillespie (1917-1993) was a jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer and sometimes singer. His technical virtuosity, intellectual prowess, and emotional fluency produced music so complex few contemporaries could follow his lead. He and Charlie Parker invented the post-Armstrong jazz dialect, often called bebop, or modern jazz.

To find Diz playing St. James Infirmary is startling, and delightful. Count Basie (1904-1984) was the face of Kansas City Jazz, taking over the old Benny Moten band in the 1930s, and becoming part of the post war royalty, with his right-hand plinking behind sturdy wind and brass riffs. These two got together with bassist Ray Brown, and drummer Mickey Roker in 1977 to give us one of Gillespie’s more accessible recordings, sans vocal.

Ellis Marsalis (1934-present) is a jazz pianist, and patriarch of a jazz dynasty, including sons Wynton (1961-present) and Branford (1960-present). Here we have Wynton and Ellis teaming up (upper right), Wynton with his own band (lower left), and Brandford (lower right). Wynton and father are celebrating, in 2006, the recovery of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. The contrast between Gillespie’s new-jazz treatment, and Wynton’s more traditional, post-classic-jazz improvisation is bridged by the timeless work of Ellis on keyboard.

Wynton (lower left) plays and sings in 2012 at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in New York. His trumpet recalls Armstrong more closely than Gillespie, but an evolved Armstrong with shades of Maynard Ferguson. His vocal ends with the fulcrum phrase, and doesn’t go into the funeral arrangements that form the return to reality in the original Armstrong number. Branford Marsalis gives us another soprano saxophone instrumental, recorded at the 2013 North Sea Jazz Festival in the Netherlands. His work is commendable but the band is sluggish and plodding, evidently trying too hard to simulate a street march.

Leon Bismark “Bix” Beiderbecke (1903-1931, at left) is a jazz cornetist whose reputation far exceeds the meager recordings he left behind. Still, from what remains it is obvious the reputation is deserved, and he is recognized as one of the most influential soloists of his era. Sadly, there are no recordings of Bix playing St. James Infirmary, but his legend has spawned, among other things, The Hot Club of Davenport (Bix’s hometown). Here is a recording of our song that would probably not exist if Bix had not existed. Unaccountably the bandleader, a Grapelli-influenced fiddle player, places the song’s origin at 1906, a date of unknown progeny. The rendition is another victory for Django styling. The lyrics never get beyond the lament for a lost lover, to the funeral arrangements of the classic version.

Bix had many imitators and the one closest to his tone and phrasing during the ‘20s and ‘30s was Jimmy McPartland (1907-1991, upper right). Jimmy is now best known as the one-time husband of Marion McPartland, British transplant whose lyrical piano and voice informed our muse over the radio for many years. Jimmy (right) has largely outgrown his “Bix” sound on this recording of St. James Infirmary, but he gives us a feeling for the spectacular runs and phrasing style of the lad from Iowa in a muted segment before the vocal, and in an open bore closing. He is joined by old Austin High buddy Bud Freeman, along with some folks from Holland. The Lyrics are Armstrong’s.

Oran Thaddeus "Hot Lips" Page (1908-1954, lower left) helped form the genre of Kansas City Jazz, although he was from Dallas. He roamed across Texas and Oklahoma for a few years before joining the father of Kansas City Jazz, Bennie Moten in 1931. He stayed with Moten heir Count Basie after Moten’s death until he led a band of his own. At left he is joined by Marion McPartland among others in a typical taste of honest Page trumpeting. Page growls the opening on his horn and then delivers Armstrong’s lyrics, with a few ad libs, in his growling voice.

James Andrew “Jimmy” Rushing (1901-1972, lower right) was another veteran and innovator in the Kansas City jazz tradition. He came out of Oklahoma City and toured the west and midwest with various artists including Jazz legend Jelly Roll Morton, before going to Kansas City with Bennie Moten and Count Basie. He worked with Hot Lips Page for a few years. His admirers are varied and eclectic including Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, Duke Ellington and Ralph Ellison. His vocal style has been described as bringing “operatic fervor to the blues.” He gives us a takeoff from the Armstrong lyrics, and it’s not over until the fat guy stops singing.

Della Reese (1931-present) is a jazz, gospel and pop singer, actress, TV personality, and minister from Detroit, daughter of a steelworker. She was discovered by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, and influenced by Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Billie Holiday. This recording is from a 1959 album about the blues genre. The arrangement and delivery are all Armstrong, with some minor jiggling of the lyrics. Not as strong as some, but more interesting than most. For those currently worrying about how to pronounce Armstrong’s first name, note how Ms. Reese handles it.

Chris Strickland gives us an amateur rendition enabled by the internet. His emotion and command of the subject are apparent, and may inspire others to try singing. Notes with the recording (see link) give a version of the song’s history.

Ian Boyter is a freelance musician in Edinburgh, and he gives us a splendid, glissando-warmed clarinet instrumental, suggesting how Barney Bigard might have done the tune, if he’d been from Scotland.

Sotto Voce is, of all things, a tuba quartet. The technique is flawless, the coloration surprisingly broad-spectrum, the power incessant, and the pleasure continuous. If you’d never heard anyone else play or sing St. James Infirmary, this is how you would assume anyone would do it. -Chris Gekker, Former Member, American Brass Quintet, Professor of Trumpet, University of Maryland: “The Sotto Voce recording is really remarkable. At first I was struck by the virtuosic ease with which the ensemble plays, and as I listened further I became more and more aware of how expressively everyone on the recording performs. Any brass player, any wind musician, will learn a lot from this stunning recording, and really enjoy it as well.”

Our best and brightest cast a scholarly eye on St. James Infirmary from Harvard Radio, WHRB, 95.3FM. Will Dingee (could this be a real person?) gives us the usual out-of-England origin story, but is non-specific about the timing and local geography. He gives us a novel verse from St.-James-for-cowboys, and several music links including Blind Willie McTell’s recording.

We formerly had a link to Dr. Dog's entry about St. James Infirmary on the blog, “The Psychedelic Swamp.” The good Dr. goes at the song from the perspective of James Booker, indicating that if Booker were a nation, this would be his anthem. At least that’s what we think it was saying. Sadly it's disappeared into the blog bog, so we've substituted the musings of a recent Nobel Prize winner.

Kenneth Goldstein wrote the notes for a 1960 Folkways record exploring the origins of the song. If you don’t have the record, you can read the notes at left.

Finally, on the lower right, we salute the commercial basis of jazz and the blues, everything has its commercial aspect, with some charting and historical information on JazzStandards dot com. This is the official story.

Janis Joplin (1943-1970) was a singer-songwriter, artist, who was born in Port Arthur Texas, led the rock band Big Brother and the Holding Company, became a major attraction at Woodstock, and was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. She attended the University of Texas, in Austin, and played briefly with a group called the Waller Creek Boys, a folk music group consisting of Joplin (autoharp and vocals), Lanny Wiggins (guitar and vocals), and Powell St. John (vocals and harmonica). This recording was bootlegged, apparently on a private recording device, in about 1962 or 1963, before her rise to fame. It’s a conventional lyric, with a few minor alterations from the Armstrong recording, forcefully hurled across the time chasm between the 1950s and 1960s, by one of the people who created it.

Youtube has some Joplin comments that may be authentic. Here are a couple, you decide. "The Waller Creek boys were Janis Joplin, Powell St. John, and Lannie Wiggins. The song was recorded by Jack Jaxon at a party of us creative outcasts in Austin. My memory is of Travis and Alice Rivers's house. I was there. You can call me Oat Willie, the part of my history that began in 1968, years after Janis had moved on to stardom. I was known as Wally Stopher back then." And this one..."I can tell you exactly where this recording is from: It was on a 45-style record printed on floppy red plastic that was included in David Dalton’s book on Janis that was published in 1972. I still have my copy. Also included among those early recordings made at Threadgill’s Bar is Janis’s brilliant cover of Bessie Smith’s Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out."

Van Morrison is a Northern Irish singer, songwriter and musician. He has six Grammy Awards, is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Songwriters Hall of Fame. If the story of St. James Infirmary coming from Ireland is true, then it has returned home. The lyrics are less like the Armstrong version, no funeral arrangements, no Stetson hat, just a lament for a dead girlfriend, very much like the apparently seminal Gamblers Blues.

Eric Clapton (1945-present) teams up with Dr. John to give us an improvisation on the Armstrong version. Clapton is an English rock and blues guitarist, singer and songwriter, and a three-time inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Dr. John’s vocal digresses as Dr. John is wont to do, but delivers his version of the funeral arrangements after Clapton sets him up with the “find a sweet man like me” phrase. Both he and Clapton jam to the outro in remarkable instrumental performances.

Joe Cocker (1944-2014) was an English singer and musician. He had one of the most parodied styles in popular music, and sometimes it is hard to tell where parody begins. Cocker uses something close to the Armstrong lyrics. He wants a thirty dollar gold piece, instead of twenty, and what sounds like “plain lace shoes,” but most significantly, he declares “And stole my baby back,” in the final verse, doubling down on the bewildering incoherence of the song. The number was included in his 1972 album titled “Joe Cocker.”

Hugh Laurie (1959-present) is an English actor writer, director, musician, singer, comedian and author. He is mostly known as the star of the TV show “House,” for which he has received two Golden Globe awards and two Screen Actors Guild awards. This St. James Inferno number comes from his 2011 album titled “Let Them Talk.” He sings the Armstrong lyrics.

Arlo Guthrie (1947-present) is a folk singer-songwriter, actor, sometime political protestor, and the son of legendary Woody Guthrie. This recording comes from his album “In Times Like These,” a live performance with the University of Kentucky Symphony Orchestra, on Arlo’s sixtieth birthday in 2007. He uses the classic Josh White lyrics that begin with Old Joe’s Bar room, and end with the “gamblers blues.”

Carls Sandburg's Lyrics from the American Songbag

Those Gambler's Blues

(now known as St. James Infirmary)

Lyrics from "The American Songbag"

by Carl Sandburg (1927)

----------------------------------

Harwood Blog

It was down in old Joe's bar-room,

On a corner by the square,

The drinks were served as usual,

And a goodly crowd was there.

On my left stood Joe McKenny,

His eyes bloodshot and red,

He gazed at the crowd around him,

And these are the words he said:

"As I passed by the old infirmary,

I saw my sweetheart there,

All stretched on a table,

So pale, so cold, so fair.

Sixteen coal-black horses,

All hitched to a rubber-tired hack,

Carried seven girls to the graveyard,

And only six of 'em comin' back.

Oh, when I die, just bury me,

In a box-back coat and hat,

Put a twenty dollar gold piece

on my watch chain,

To let the Lord know I'm standin' pat.

Six crap shooters as pall bearers,

Let a chorus girl sing me a song,

With a jazz band on my hearse,

To raise hell as we go along."

And now you've heard my story,

I'll take another shot of booze,

If anybody happens to ask you,

Then I've got those gambler's blues.

Josh White's Lyrics

It was down by old Joe's barroom, on the corner of the square

They were serving drinks as usual, and the usual crowd was there

On my left stood Big Joe McKennedy, and his eyes were bloodshot red

And he turned his face to the people, these were the very words he said

I was down to St. James infirmary, I saw my baby there

She was stretched out on a long white table,

So sweet, cool and so fair

Let her go, let her go, God bless her

wherever she may be...

She may search this whole wide world over

never find a sweeter man as me....

When I die please bury me in my high top Stetson hat

put a 20 dollar gold piece on my watch chain

The gang'll know I died standing pat

Let her go, let her go God bless her

Wherever she may be

She may search this wide world over

Never find a sweeter man as me

I want 6 crapshooters to be my pallbearers

3 pretty women to sing a song

Stick a jazz band on my hearse wagon

Raise hell as I stroll along

Let her go Let her go

God bless her

Wherever she may be

She may search this whole wide

world over

She'll never find a sweeter

Man as me..

Songwriters

MILLS, IRVING

Published by

Lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

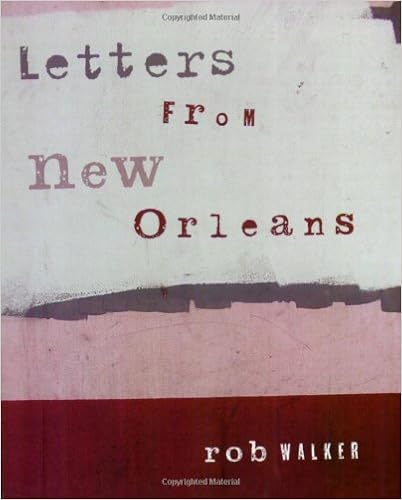

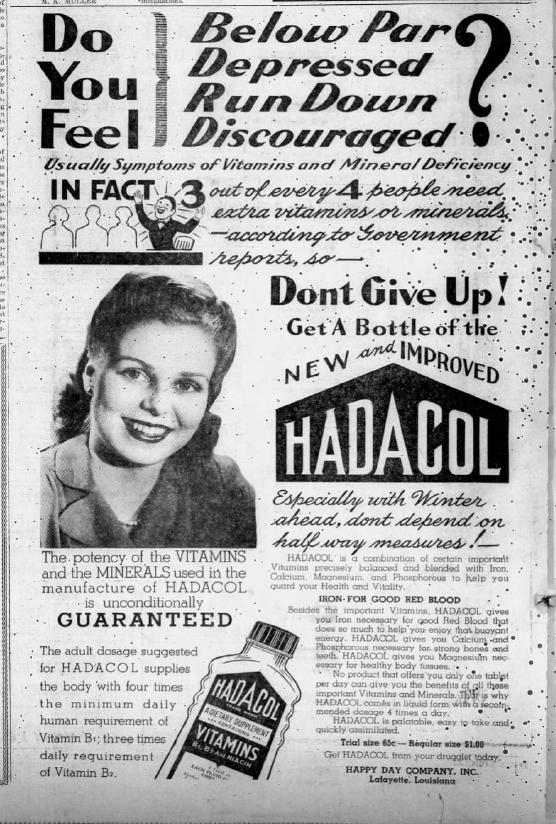

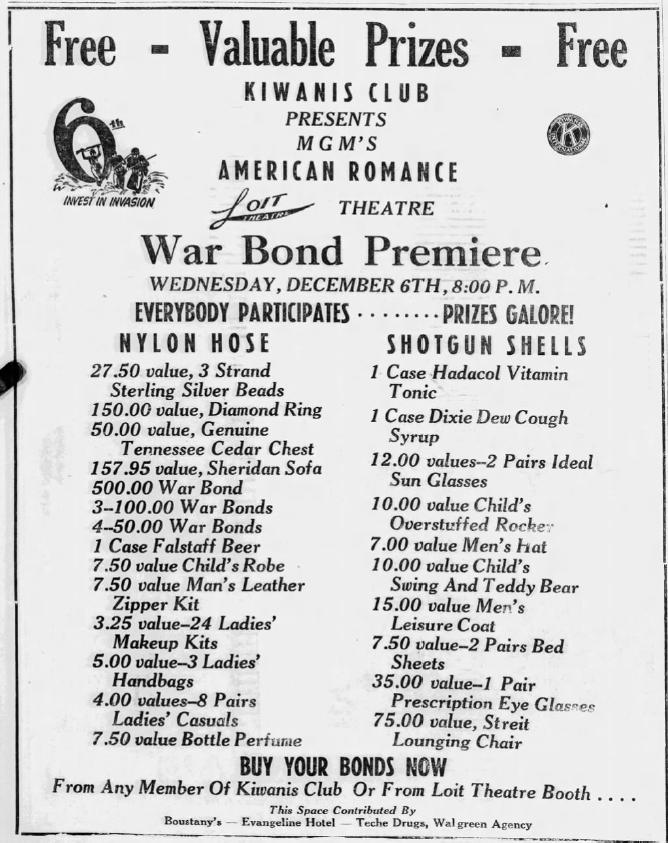

LeBlanc is credited with a "sophisticated" advertising campaign. Here is a sampling of newspaper ads from 1944-1950.

LeBlanc built a brand new builing in Lafayette in 1950-1951. It was rented to the Parish government 15 years later.

Hadacol Hines

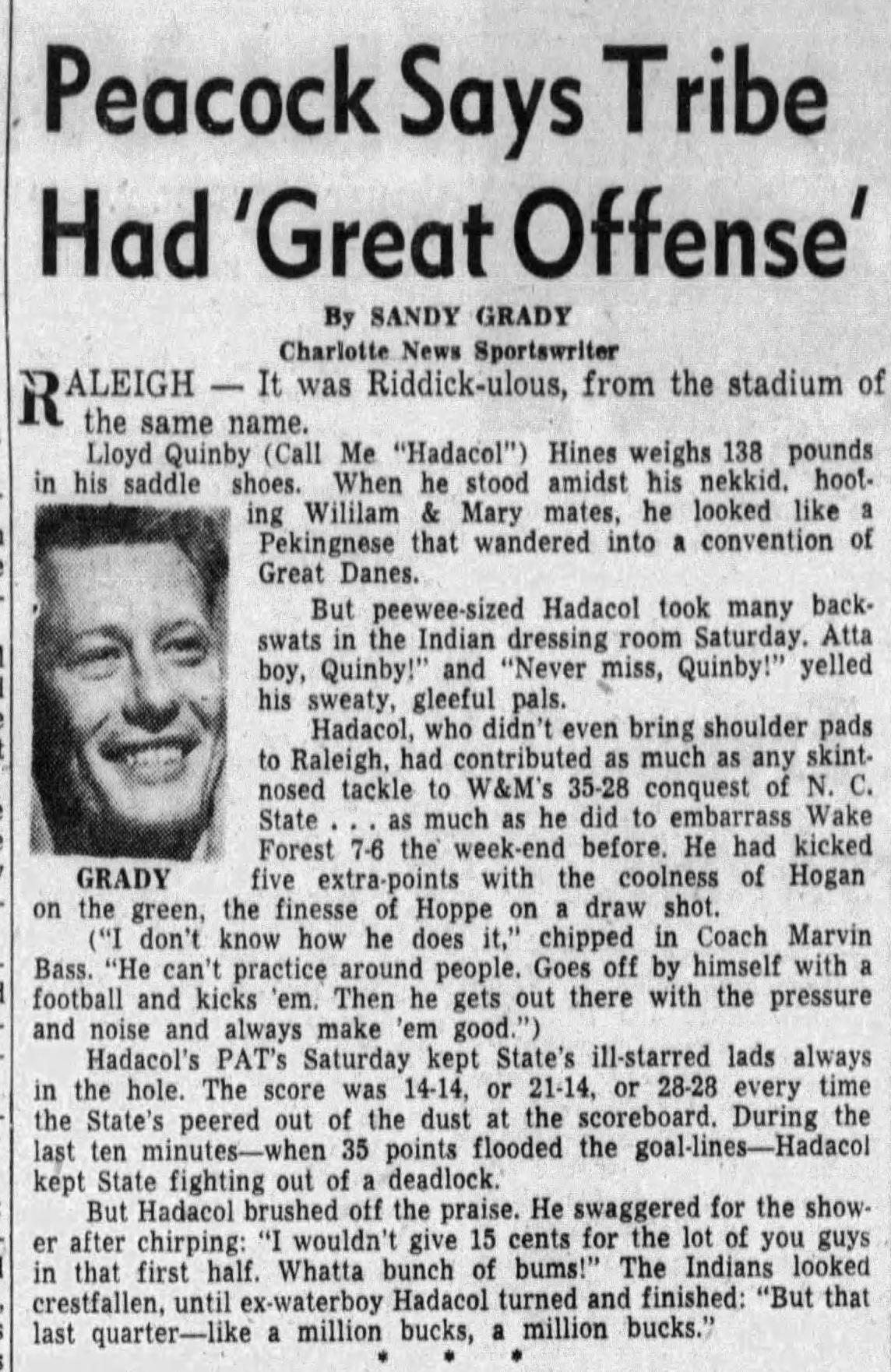

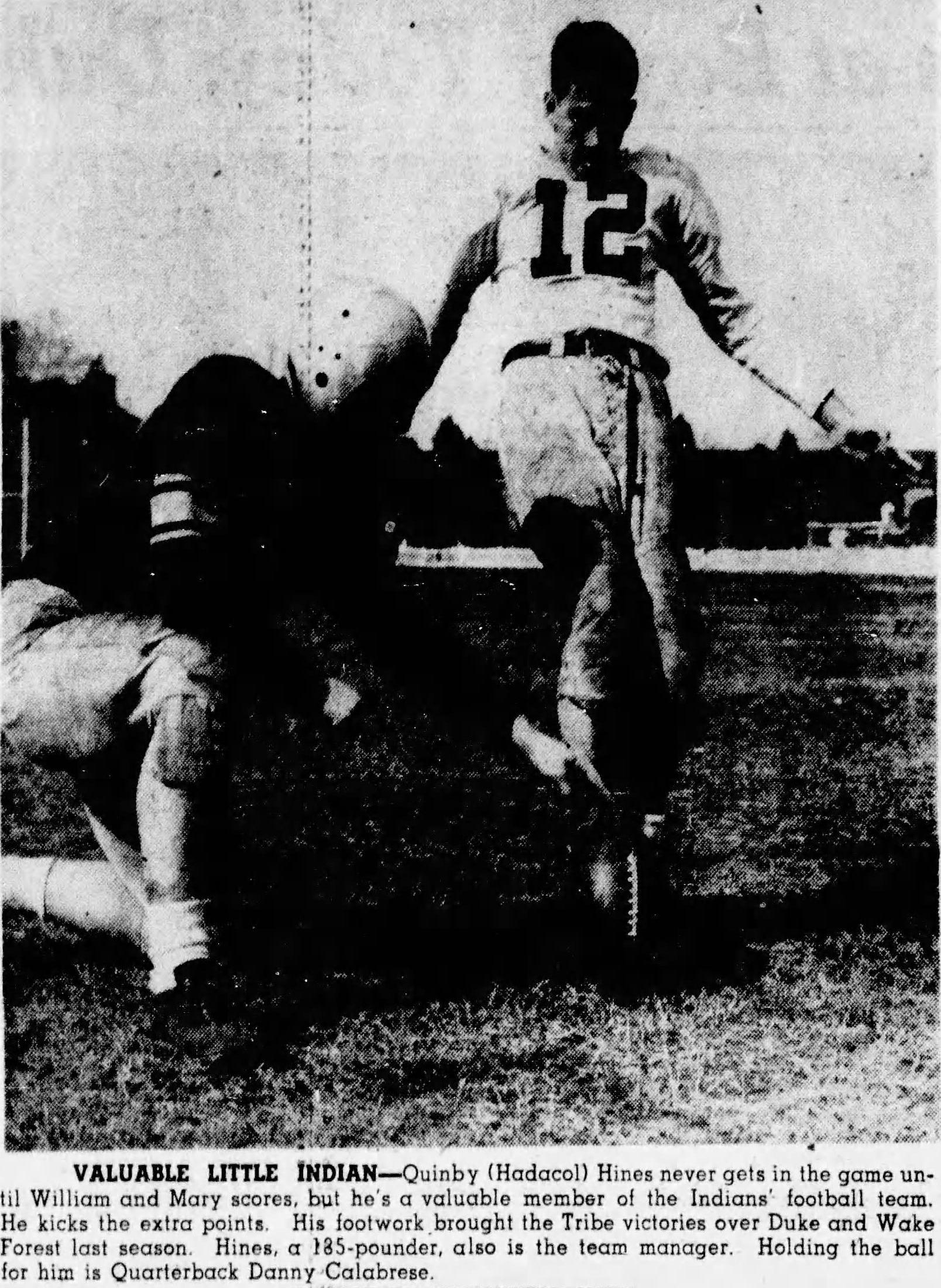

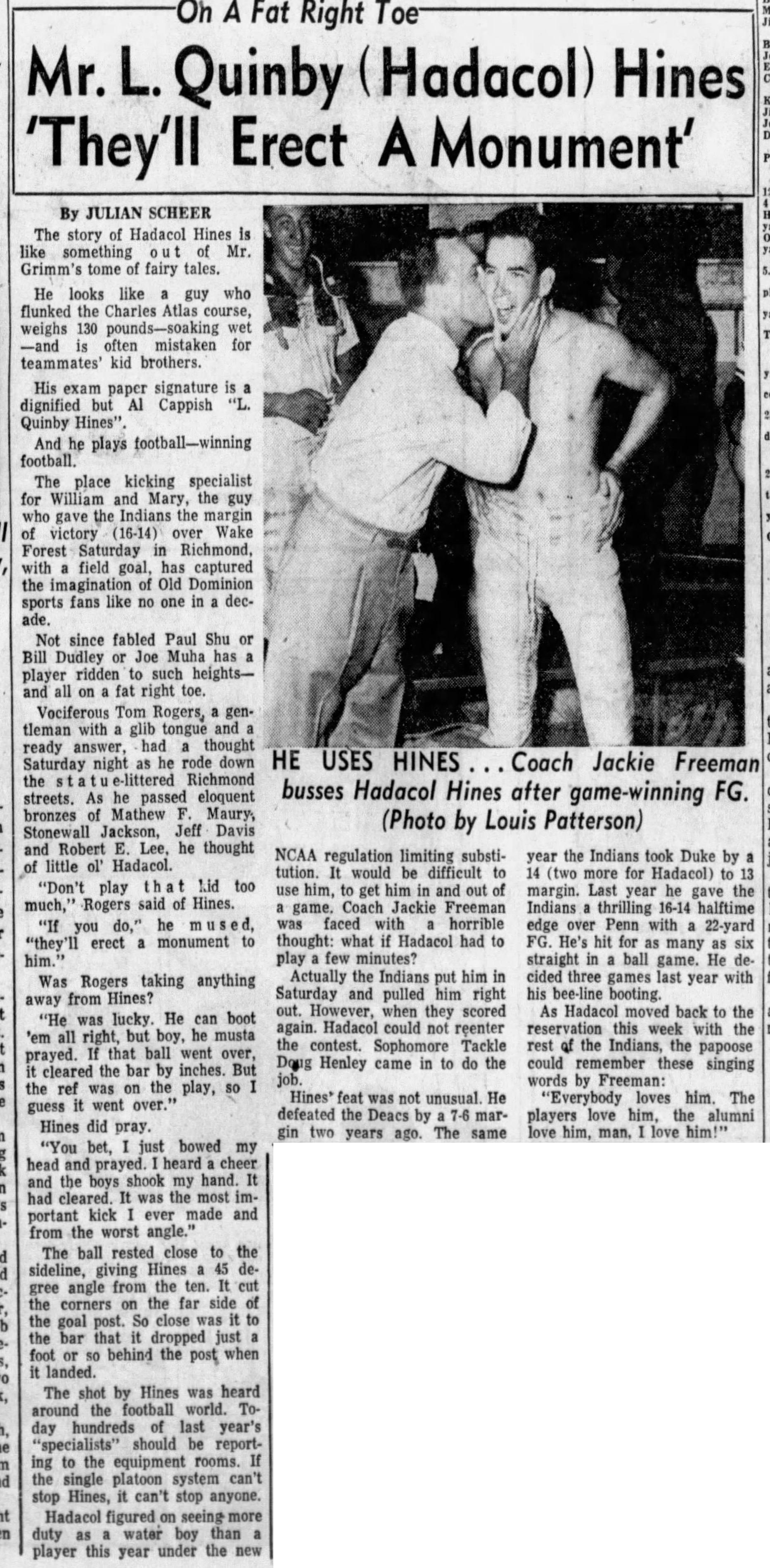

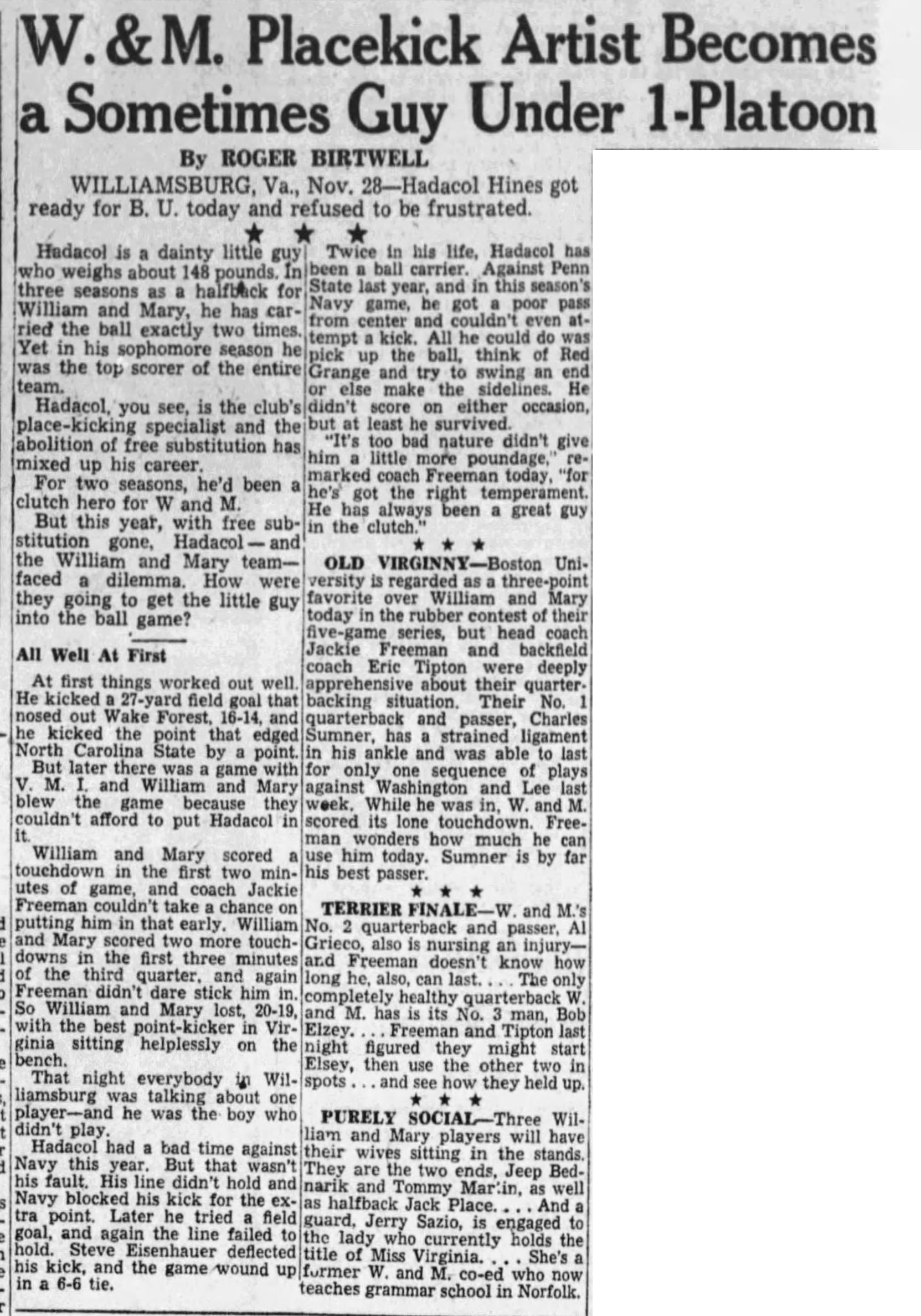

Lloyd Quinby Hines, Jr. was a place-kicking specialist for William and Mary in the early 1950s, during a time when specialties were largely unknown in football. He was small for a football player, but his skill and determination won several games for the Indians, who became known as the "Iron Indians" during the 1953 season. Because of his talent and size, sports writers dubbed him "Hadacol Hines," Hadacol having become a catchword for unexpected physical prowess.

His nickname seems to have been mainly a device of sports writers. It doesn't appear in his yearbook, or in his obituary, and seems not to have followed him into his successful business life, as college nicknames sometimes do. Below are a series of news articles recalling his moment in the sports spotlight.

THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT

Saturday, July 30, 1994

L. QUINBY HINES JR.

Mr. Lloyd Quinby Hines Jr., 62, died Friday, July 29, 1994, in a hospital.

A native of Suffolk, he was vice president of Ferguson Manufacturing Co. Mr. Hines was a graduate of Suffolk High School and the College of William and Mary, where he was a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity. He was a member of the ``Iron Indian'' football team in 1953, where he held a national record in extra point totals. He was in the William and Mary Sports Hall of Fame and was a member of South of the James Alumni Association. Mr. Hines was featured in the book, ``Great and the Near Great--a Century of Sports in Virginia,'' by Abe Goldblatt and Robert W. Wentz Jr. He was a former president of the William and Mary Educational Foundation.

Mr. Hines served as first lieutenant in the U.S. Army in Germany. He was a member of Main Street United Methodist Church and was active on its administrative board and had served as superintendent of Sunday Schools. He was past president of the Suffolk Swimming Pool Association and the Nansemond River Yacht Club. He was a member and served on the board of the Suffolk Rotary Club. He was active with the Suffolk Chamber of Commerce and the Suffolk-Nansemond Historical Society, having served both as treasurer. Mr. Hines served on the Salvation Army Board and was a member and former board member of the Southern Farm Equipment Association. He was a member of the Suffolk Art League.

Mr. Hines was preceded in death by his father, Mr. Lloyd Quinby Hines Sr. Survivors include his wife, Ann Callihan Hines; two sons, Marc Cambridge Hines of Virginia Beach and Bruce Quinby Hines of Suffolk; two daughters, Daphne Hines Mayhew of Richmond and Anne Caroline Hines of Winston-Salem, N.C.; his mother, Elizabeth Jennings Hines of Virginia Beach; two sisters, Sue Hines Davis of Suffolk and Ann Hines Fuller of Portsmouth; three grandchildren, Cambridge Hines, Finley Hines and Marshall Mayhew; three nieces and two nephews.

Graveside services will be conducted at 11 a.m. Monday in Cedar Hill Cemetery. The family will receive friends Sunday from 4 to 7 p.m. at their home. Memorial donations may be made to the Salvation Army or the Memorial Fund of Main Street United Methodist Church. R.W. Baker & Co. Funeral Home is in charge of arrangements.

Who in the world cares about St James Infirmary?

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6788390-1445123889-7641.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/A-128576-1546089302-9277.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-4805189-1376183068-1935.jpeg.jpg)