Comments?

Dateline:August18, 2025

It's the Big One

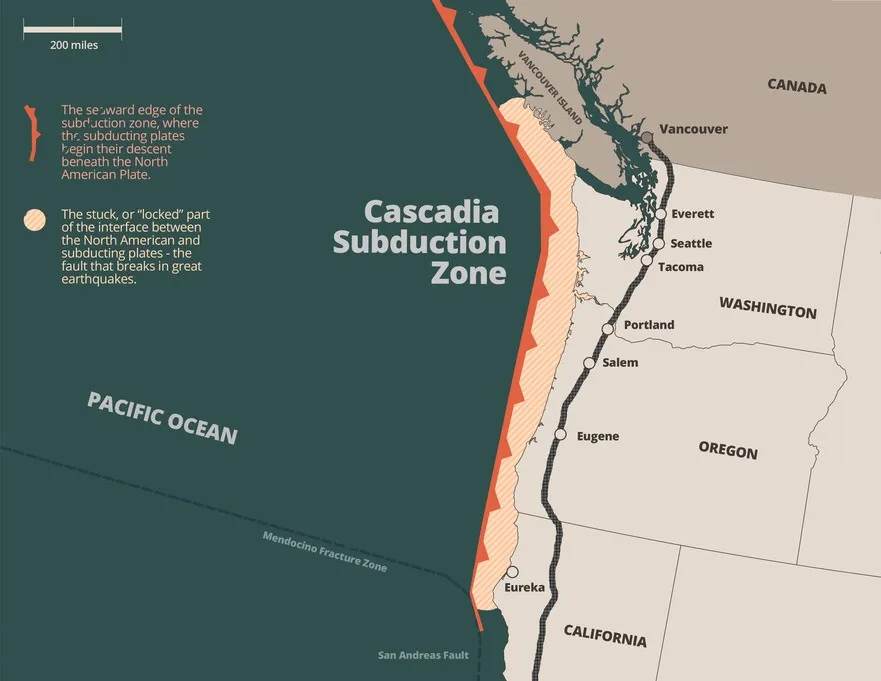

The Cascadia Subduction Zone: Be Afraid, Very Afraid

An ancient puzzle called the "ghost forest," in Washington State's coastal region of the Copalis River, was originally "solved" by theorizing that a slow salt-water inundation, from gradual subsidence, had killed the cedar trees.

Then, the trees were ring dated, and it was discovered they'd all died in the winter of 1699: no leisurely geologic process involved. This discovery was linked to a dawning scientific awareness of an unsuspected source of earthquakes: subduction zone slippage.

The ghost forest sits in the middle of the historically dormant Cascadia Subduction Zone. The written history of the region begins after 1700, the time of the tree deaths, but the oral history has tales of catastrophe: the annihilation of tribes living in the Vancouver and Oregon regions, by sudden floods.

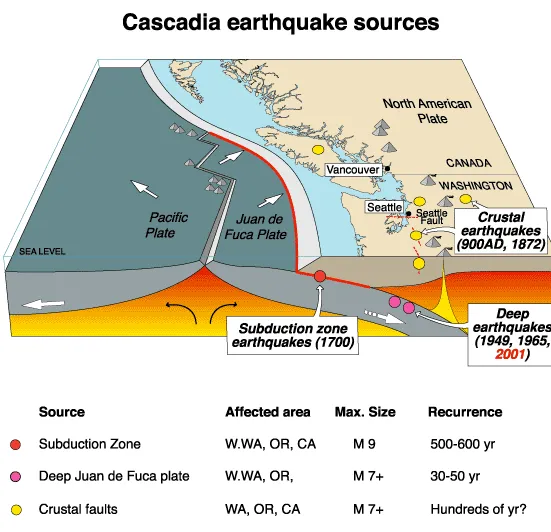

On the other side of the Pacific, in Japan, there were written, dated records of an orphan tsunami: a great wave associated with no known earthquake. The orphan tsunami was linked to the ghost forest and it was realized a magnitude-9 earthquake had hit the Vancouver/Oregon area in 1700.

Using the Japanese history, and allowing for the propagation of the wave across the Pacific, scientists were able to pinpoint the time of the earthquake remembered in tribal traditions to January 26, 1700, at 9:00 p. m. The picture above links to Discover Magazine's account of the solving of this mystery.

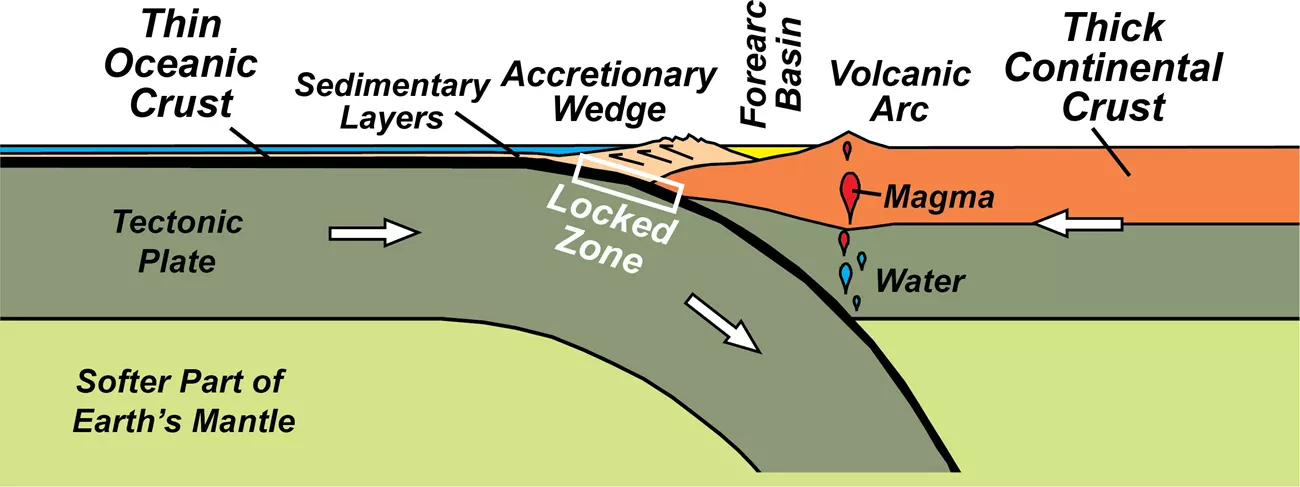

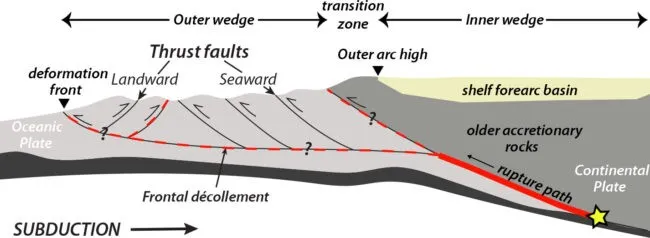

Nine years prior to the Discover Magazine article, the National Geographic publicized the scientific evidence and growing concern. Attention to the inevitability of the next big quake in the region was stimulated by the devastating tsunami in Japan, in 2011. The 2011 earthquake in Japan was more friendly to the American Pacific coast in 2011 than the reverse process had been to Japan in 1700. Communities Digital News did a story in 2014. The article emphasizes the destructive potential and discusses survival policy. The Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology have an essay on the subject, including a video of the subduction process.

Sometimes tales told around ancient campfires can be assumed to be primitive imaginings. As we accumulate more information in our universal quest to understand ourselves, we sometimes connect those campfires to what we call reality. Two tribal tradtions, separated by an ocean, and connected by its waves, have fit neatly into our new theories about the planet we share.

Southern New Mexico a War zone in 1880

Southern New Mexico, at the time of President Hayes' visit is often referred to as a war zone. Lawlessness of all sorts flourished, and was a major concern of the military, and such civil law enforcement as existed. Non-military attempts at law enforcement largely consited of local militias, which were themselves controversial, and sometimes considered part of the lawlessness. In fact, Albert J. Fountain, of later unfortunate renown as the victim of a still unsolved disappearance near the White Sands in 1896, gained much of his stable of enemies and followers as a leader of militias hunting down rustlers. The links on this page, are to four introductory sources about the southern New Mexico security situation in late 1880, when Hayes, Sherman, Alexander et al jogged in primitive transportation across the desert behind army mules and a handful of soldiers.

The first sets the scene around Fort Cummings, a little north of present day Deming, New Mexico, describing the Apache situation, as well as the mail robberies, train robberies, and other mischief.

The second is a letter from the citizens of Silver City, the most developed town in southern New Mexico at the time, to the president of the United States, asking for relief from Indian depredations, followed by the response of General Pope.

The third is a 1935 discussion of General Buell's excursion into Mexico in pursuit of Victorio, just before the president arrived. It gives a short history of the Mescalero Apache troubles from 1863 to 1880, and then describes the coordination with Mexico about the troubles around the border as Victorio fled south.

The fourth is the alert from General Phillip Sheridan to General John Pope advising him of the president's visit.

We can suffer a failure to visualize

when we read about Hayes and his party traveling by military ambulance. In the southwest the Army was using anything with wheels to transport goods and people. All we know for sure is Ramsey's description of the six-mule teams, unusual for a wagon full of people. The army was anxious to get across the desert quickly, and six were faster than four.

Franz Schubert : The Trout (Die Forelle)