Comment?

Comment?

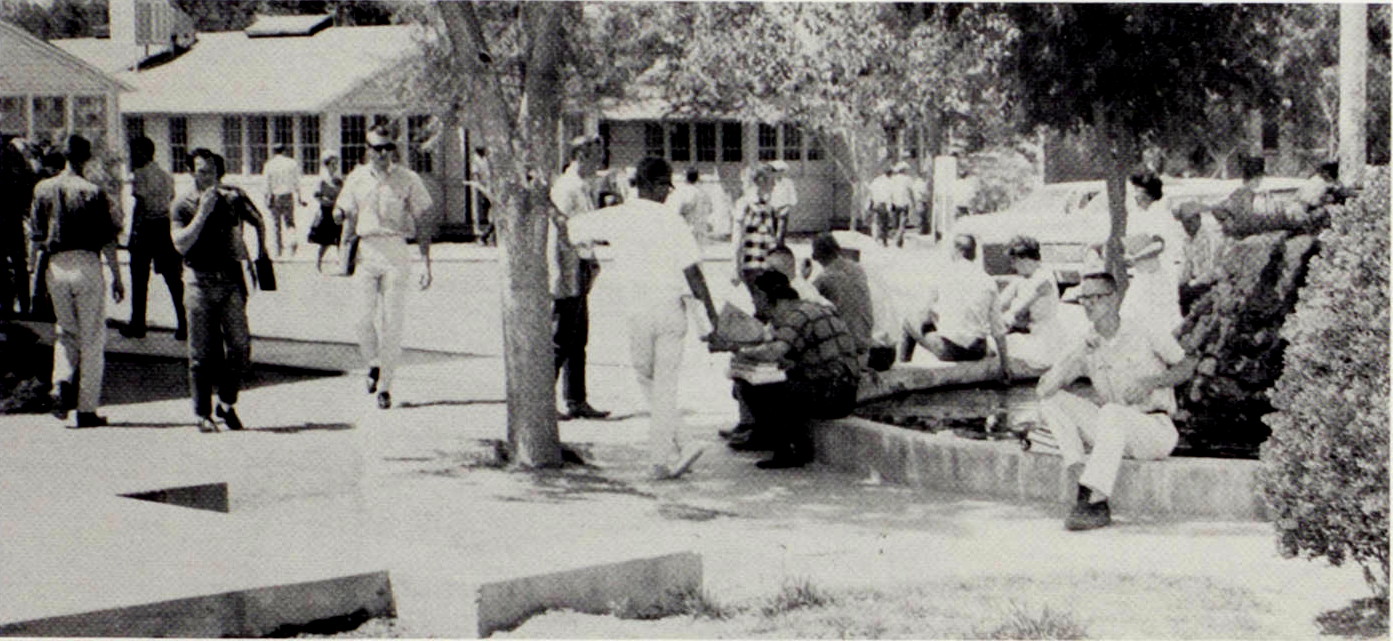

My 1960 acceptance letter from New Mexico State University assigned me to a dormitory called White Rock, an exotic sounding place to a seventeen-year-old from Carlsbad.

In the blush of that vernal autumn I arrived with conventional gear and airy surmise. It was the days of slide rules and portable typewriters; record players and footlockers; brief cases and spiral notebooks. I even brought a shelf of real books.

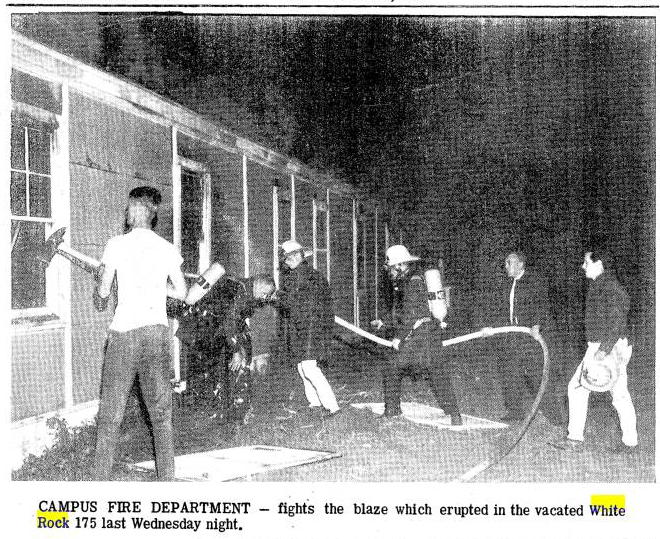

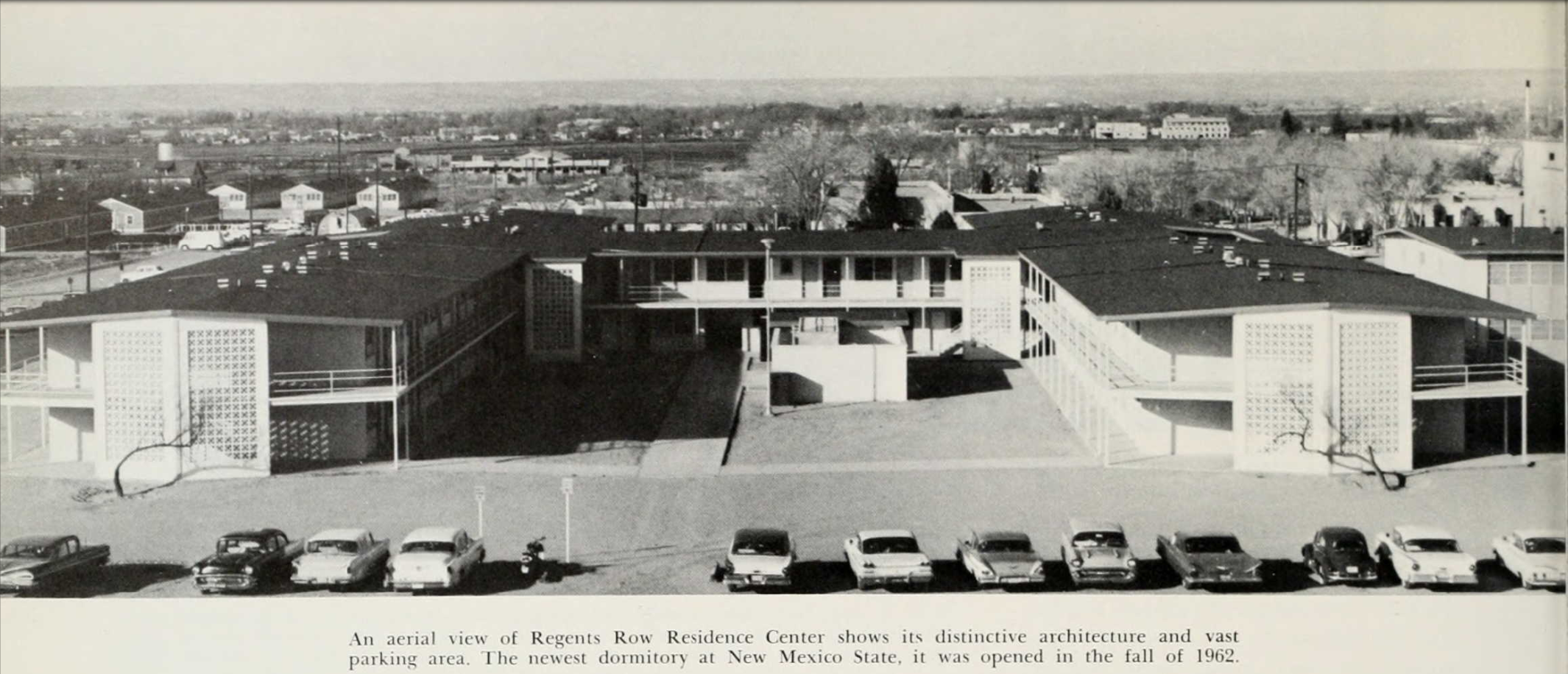

The dorm proved to be a collection of recycled barracks from White Rock, New Mexico. Surplus WW II barracks were the go-to temporary buildings of the day, and they'd been pulled onto the campus in response to the GI Bill. There was no air conditioning. The bathrooms and washing machines were in the middle of the building, near a tiny lobby with ugly chairs. I lived in White Rock one semester until the slick new Regents Row complex opened. We haven't found many actual pictures of White Rock, save from a story about one of them burning in 1966, and a distance shot below, so we've included some protypical views from other venues to suggest the moment. If you're wanting to flip through some old NMSU yearbooks about now, click the title block, at the top.

White Rock Barracks just before destruction in 1963

From the Santa Fe New Mexican-July 1, 1973:

White Rock: Resurrection City

Ghost towns proliferate in the southwest, but who ever heard of one that gathered up its shroud and recycled itself into a model city? White Rock did! The new White Rock is a city of 9,000 people, with not a slum or ghetto area in sight. It is all new, and might well serve as a specimen sample for slick magazines. Homes are not cut from cookie cutter master plans, but express the individuality of tastes and needs. They share well manicured lawns, shrubbery and trees, winding paved streets, and a business section that refuses to be stereotyped, yet is completely efficient and more than attractive. Walk though "The Village", a multimillion dollar business center being developed by Andy Long with diminutive dynamo Peggy Corbett as his good right hand. The buildings are mission stone with shake shingle roofing. Grouped with open areas, minus gaudy, glaring signs, the center has trees, redwood planters, hanging flower planters, shaded portals, even a small coral adjacent to a western wear and tack shop. The professional plaza is already in use. There is a fabric shop with a children's play center, a "findings" department with jars of hard candy to help patrons make up their mind on which pattern to use and a sewing training center. Customers often bring in their creations for others to see how a fabric or pattern looks made up. An ice cream "saloon", barber shop, shoe shop, beauty parlor are already thriving, and plans call for a supermarket, gift shop, apartment houses, etc. in the complex. Play centers for children, parks and tennis courts are scattered throughout the town, and the view in any direction is superb by courtesy of nature. Schools, churches, fire and police departments are all excellent. White Rock is a suburb of Los Alamos, now connected by a high bridge over the narrow, deep canyon that separates the two cities.

In 1962, the first homes of the second White Rock were occupied and today it continues to grow. It is small enough to be friendly and large enough to care for its people realistically. It is really a dream town. When Los Alamos was chosen as the site for the secret Manhattan project, the laboratories developed around Fuller Lodge and Ashley Pond. It was the secret city, the gate opened only to those with the even for laboratory personnel. Contractors were loathe to even bid if it meant transporting their workers from Santa Fe or Espanola. Nearby was a stretch of flat land bordering on the gorge of the Rio Grande. Here a prefab town was built at a cost of $4,500,000 for construction workers. Streets were laid out, water, electricity, sewer lines were all installed and White Kid-size water fountains in "The Village." As it grew, officials decided that the main laboratories needed to be moved out of the prefab housing into a permanent location. This was in 1949. Construction people had to have somewhere to live, and certainly Los Alamos facilities were inadequate, White Rock was born. AEC put in 411 homes, 197 trailer spaces, 21 dormitories, an elementary school, food market, barber and beauty shops, drug store, a clothing store, doctor and dentist offices, a service station, police and fire departments. In short order it was a town of 2,000 people. An interesting sidelight surfaces in that the drug store had a liquor license, verboten in Los Alamos. They would and did deliver to the Atomic City. When the new laboratory buildings were completed, construction workers speedily moved out. White Rock rapidly became a ghost town, while the barracks type buildings were sold.

From the Santa Fe New Mexican-July 1, 1973: White Rock: Resurrection City Ghost towns proliferate in the southwest, but who ever heard of one that gathered up its shroud and recycled itself into a model city? White Rock did! The new White Rock is a city of 9,000 people, with not a slum or ghetto area in sight. It is all new, and might well serve as a specimen sample for slick magazines. Homes are not cut from cookie cutter master plans, but express the individuality of tastes and needs. They share well manicured lawns, shrubbery and trees, winding paved streets, and a business section that refuses to be stereotyped, yet is completely efficient and more than attractive. Walk though "The Village", a multimillion dollar business center being developed by Andy Long with diminutive dynamo Peggy Corbett as his good right hand. The buildings are mission stone with shake shingle roofing. Grouped with open areas, minus gaudy, glaring signs, the center has trees, redwood planters, hanging flower planters, shaded portals, even a small coral adjacent to a western wear and tack shop. The professional plaza is already in use. There is a fabric shop with a children's play center, a "findings" department with jars of hard candy to help patrons make up their mind on which pattern to use and a sewing training center. Customers often bring in their creations for others to see how a fabric or pattern looks made up. An ice cream "saloon", barber shop, shoe shop, beauty parlor are already thriving, and plans call for a supermarket, gift shop, apartment houses, etc. in the complex. Play centers for children, parks and tennis courts are scattered throughout the town, and the view in any direction is superb by courtesy of nature. Schools, churches, fire and police departments are all excellent. White Rock is a suburb of Los Alamos, now connected by a high bridge over the narrow, deep canyon that separates the two cities. In 1962, the first homes of the second White Rock were occupied and today it continues to grow. It is small enough to be friendly and large enough to care for its people realistically. It is really a dream town. When Los Alamos was chosen as the site for the secret Manhattan project, the laboratories developed around Fuller Lodge and Ashley Pond. It was the secret city, the gate opened only to those with the even for laboratory personnel. Contractors were loathe to even bid if it meant transporting their workers from Santa Fe or Espanola. Nearby was a stretch of flat land bordering on the gorge of the Rio Grande. Here a prefab town was built at a cost of $4,500,000 for construction workers. Streets were laid out, water, electricity, sewer lines were all installed and White Kid-size water fountains in "The Village." As it grew, officials decided that the main laboratories needed to be moved out of the prefab housing into a permanent location. This was in 1949. Construction people had to have somewhere to live, and certainly Los Alamos facilities were inadequate, White Rock was born. AEC put in 411 homes, 197 trailer spaces, 21 dormitories, an elementary school, food market, barber and beauty shops, drug store, a clothing store, doctor and dentist offices, a service station, police and fire departments. In short order it was a town of 2,000 people. An interesting sidelight surfaces in that the drug store had a liquor license, verboten in Los Alamos. They would and did deliver to the Atomic City. When the new laboratory buildings were completed, construction workers speedily moved out. White Rock rapidly became a ghost town, while the barracks type buildings were sold. Some of these buildings can still be seen scattered around the nearby countryside including Espanola. A few Los Alamoites, AEC, LASL and Zia employees, living at White Rock until quarters could be built in Los Alamos, moved into the hill city as rapidly as possible. Gov. Edwin L. Mecherti cut the ribbon across the road into Los Alamos on Feb. 2, 1957 to open the secret city. New Mexicans, enroute to Bandelier, sometimes paused and rambled around the White Rock site and not knowing why it was built to begin with, readily believed the story that Los Alamos people simply didn't want to live in White Rock. Housing problems in Los Alamos proliferated. Barranca was the first "suburb" of privately owned homes to be built. Robert Y. Porton, PR Director, recalls that pessimists preached doom for that housing area, and even more so when, in 1959, White Rock was suggested as a development site. The government was withdrawing completely as landlord, contractor and head of various factors that go to make up a city. Housing for workers remained a problem, and bids were opened with E.I. Noxon Construction Company of Los Angeles being awarded the contract to develop the first 250 acres by AEC in 1961. The old White Rock facilities—water, sewage disposal, lights, etc. had not only deteriorated during the "ghost town" period, but were simply inadequate for the new project. They were replaced, Roger and Peggy Corbett bought, and still occupy, one of the first houses in the new White Rock. They now have lots of happy, contented neighbors.

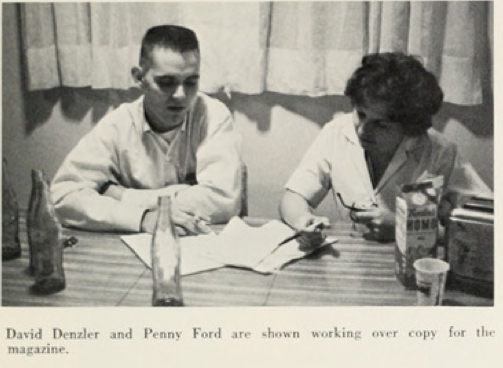

David W R Denzler, Roomie

My roommate was David Denzler, also a freshman, but with a difference. David had graduated from Albuquerque Adademy, a prestigious private school, and was eons ahead of me in sophistication. He majored in mathematics, because, he said, the weirdest people he knew were mathematicians. His high school Latin teacher had been the poet, Robert Creeley and David had lots of stories. David loved classical music, opera, and literature. He had a girlfriend, owned a car, and knew how college life should proceed. He'd even attended a semester at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, marking him as a venerated elder, although he was younger than me.

I was without such savoir vivre, but barely realized it. I wanted to be a physicist, and had a goal of learning everything. I had a staggering case of homesickness that nearly put me on a bus back to Carlsbad. I affected a taste in jazz, although I tolerated David’s classical stuff, since he owned the record player. In retrospect I see my musical taste as a mimic of that era's intellectual cool set. Eventually, I changed my major to math also, because it was easier than physics, and I was beginning to suspect I wouldn't be able to learn everything.

David realized the beds in our tiny room were stackable. That freed up space for the easy chair he'd hauled down from Albuquerque. He spent a lot of time in it, reading, studying, and philosophizing. He had a souvenir limp from a bout of childhood polio, but he made no concession to it, except for a few life-style modificaitons. He had rigged a left-side accelerator pedal on his car for when his right foot grew tired on long trips. His parents visited a few times and they took us out to dinner at La Posta. His father was a well-known doctor in Albuquerque. David's pride was a meerschaum pipe. He also got brownies from home, which he shared from a fruitcake box kept in the closet. He was a valuable asset to a bewildered young freshman, although I didn't realize it at the time, and wouldn't admit it to myself for years.

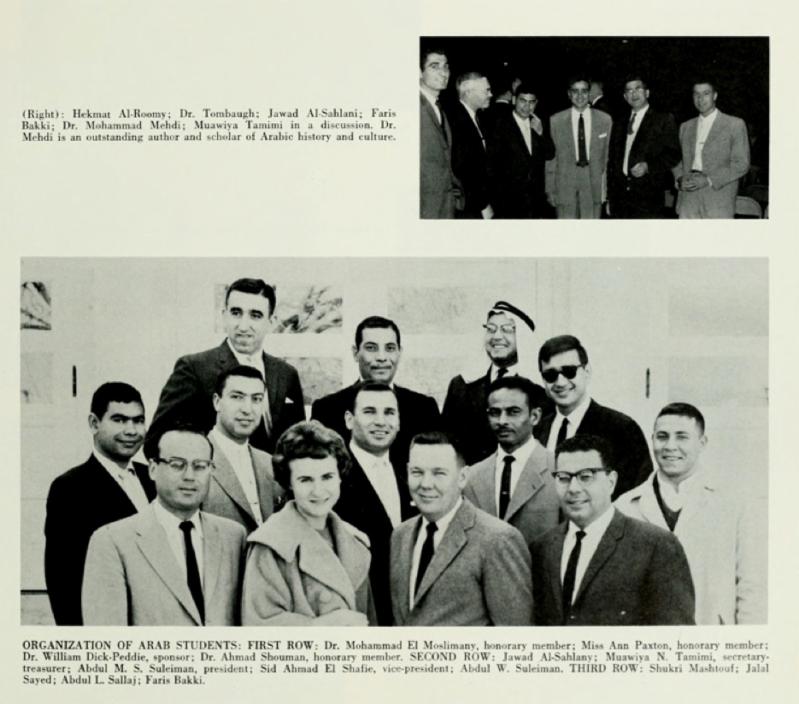

All the rooms were off a single hall, and ours was the first room nearest the parking lot. We got a lot of visitors, partly because of our location, and partly because of David’s gregarious and scholarly mien. People were always dropping in for help with homework or just friendly advice from the Sage of White Rock. He made friends among some of the foreign students, from Iraq and other middle eastern countries.

One of these, Farris Bakki (see above), introduced us to Turkish coffee, and became a confidant and portal to the world beyond. Dave and Farris shared a love of Madame Butterfly. There was always a discussion going on.

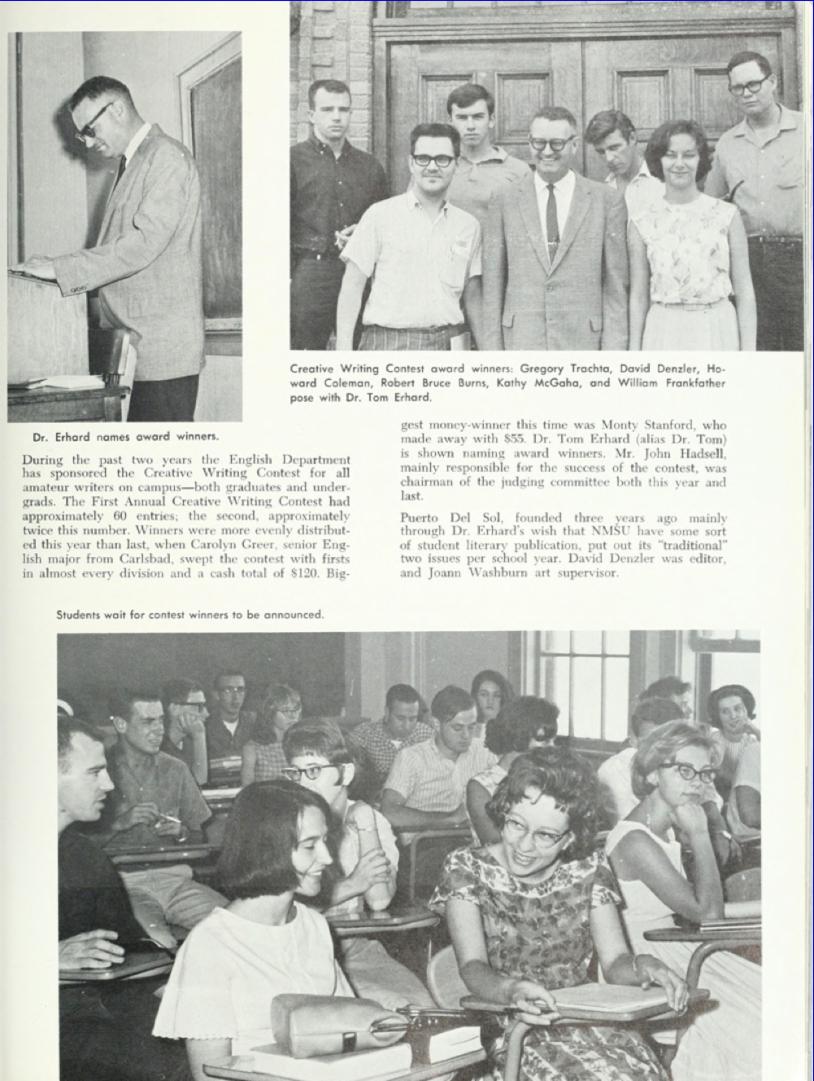

David involved himself with Frank Thayer, another White Rock resident, in reviving the campus literary magazine, renamed Puerto del Sol.

Marion Hardman, campus legend, and longtime stalwart of the English Department, had helped found the Rio Grande Writer, at some point in the 30s or 40s. It died in 1949 from lack of interest, and in early 1960, newly arrived Tom Erhard conspired to reignite the long cold ashes. Frank Thayer, Denzler, and others helped him get it going again, with a new name, during the 1960-1961 term.

For some reason the current English Department thinks literary life at NMSU began in 1964, but the youth have a fuzzy concept of history.

One night a frequent visitor, it might have been Charley Weaver, wandered in to get David's help with a math problem. He paused as if seeing the room for the first time and observed to the assembled, “This room has a lot of character.” He was right.

David Sears, Denizen of White Rock

Denzler made friends with David Sears, another White Rocker from the other end of the long hall, and the three of us hung out frequently in our spare time. David Sears was from Georgia, and had a jazz collection acquired from various junk shops. Today we would call these relics, “78s,” but at the time they were just records, distinguished from LPs and 45s. That jargon and its nuances are now as foreign as slide rules and typewriter erasers.

I knew very little about jazz at the time, an ignorance of which I was largely ignorant, having heard of Dave Brubeck, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and little else. My older brother was a jazz aficionado, so naturally I assumed I knew about it too. David Sears introduced me to Bix Biederbecke, Fletcher Henderson, Bubber Miley, Cootie Williams, Jimmy Rushing, Jimmy McPartland, and a slew of other artists I've cherished since.

David Sears had a Grundig tape recorder, reel-to-reel of course, and he agreed to record some of his collection for me. The Grundig was a wonderful machine. Push a button, and lights flashed, spindles whirred, relays clicked, and armatures maneuvered, during a moment of mechanical ponderation. Then, smooth-as-fresh-cream, it took off like a wisely trained race horse (I was learning similes and metaphors in Freshman Comp). We made two tapes of my favorites from his collection. I typed up notes. The Grundig picture links to a Jimmy Rushing song we would have recorded if David had owned a copy.

The tapes have survived, with only a short interval of magnetic interference owing to me hitting record, decades ago, during a playback. I had no way to play them after about 1970, until I recently had them transferred to digital media. Some day I need to capture the notes as well.

Now, of course, many of the recordings can be found online. One of our favorites was Barney Bigard playing “Steps Steps Up,” and “Steps Steps Down.” There was a lot of Coleman Hawkins, a little Duke Ellington, and some great Jimmy Rushing.

I lost track of David Sears. He left NMSU about 1963, and, as I recall, headed for California. He may have been an IT consultant in Atlanta, but I’m not sure. I hope, wherever he went, he kept those records, and that magnificent Grundig machine. What a piece of engineering that was.

We all moved out of White Rock Barracks at the start of the next semester, into the swanky knew digs called Regents Row. That soon-to-be-demolished complex was the dream dorm of its time: air conditioned with a bathroom shared between two rooms. I learned the word "suitemate," and found out how to manipulate the sealed thermostat by draping a damp cloth over it. My education was thorough. My next three years were spent in Garcia Hall, now an administration building, more primitive than Regents Row, but lower "camping out" credentials than White Rock.

I now recognize my White Rock experience as a watershed. My old roommate and I seldom saw each other during the next three years, but the friendships, acquaintances, and social understandings acquired in that first year informed the botheration that followed.

David Denzler went on to be the editor of Puerto del Sol, and encouraged my writing efforts, and we both formed friendships with an important mentor, Tom Erhard, in the English Department (see link above). That semester at White Rock is the nmeonic touchstone for my college days.

As posted in the "Las Cruces News"

Longtime 'Voice of the Aggies' dies at age 90

By Frank Thayer

Posted: 11/12/2013 03:23:15 PM MST

For 35 years, the "Voice of the Aggies" never missed announcing a home football or basketball game for New Mexico State University, and it earned a place in NMSU's Athletic Hall of Fame for Thomas Erhard who died Sunday in Las Cruces at age 90.

While he was a dedicated Aggie fan and sports announcer, Tom Erhard was better known to hundreds of students and faculty as a professor in the English and the Theatre Arts departments, while also familiar to many thousands nationwide as the author of 39 plays for both young people and adult audiences.

A celebration of Tom Erhard's life was held at La Posta, Thursday Nov. 14 at 3 p.m. for his wide circle of family, friends and colleagues.

Erhard began his NMSU career in 1960 and retired as a full professor in 1991.

He had been in weakened condition for several months and was at Mesilla Valley Hospice since last Saturday. He died quietly early Sunday morning.

Born June 11, 1923, in East Hoboken, N.J., Erhard earned his bachelor's at Hofstra College in Hempstead, N.Y., in 1941. After military service in World War II, he returned to academics. His master's (1950) and doctorate (1960) were earned at University of New Mexico.

During WWII, Erhard was drafted into the U.S. Army and stationed at Camp Shanks, N.Y., where his assignment was to play baseball. Erhard rubbed shoulders with similarly drafted and volunteer professional ballplayers who joined the Army. Erhard said Hall of Famer Stan Musial, of St. Louis Cardinals fame, was especially a mentor to him.

Erhard taught English and journalism at Highland High School from 1949-1953, and served as director of public information for the Albuquerque Public Schools from 1953-1956 where he founded its Public Information Department.

He went on to become assistant director of press, radio and TV relations for the National Education Association in Washington for a year in 1957 before taking a position as senior fellow in the English department at UNM in 1959 while completing his doctorate. He then moved to NMSU in Las Cruces where he spent a 31-year professorial career starting in 1960. He retired as a full professor in 1991.

Of his many plays for young people, "Rocket in His Pocket" was one of several that achieved national fame, and the royalties from the play were sufficient to finance all the costs of his doctoral studies at UNM.

In more recent years, Erhard was commissioned by NMSU to write the play "And Here Come the Aggies" in celebration of the university's centennial year. He co-wrote the play with his wife of 34 years, Evelyn Madrid Erhard. The two also collaborated in the dramatic adaptation of the Frank Waters novel "The Woman of Otawi Crossing" produced in Reader's Theatre at NMSU in 1989.

As part of his service to education in New Mexico, Erhard founded the New Mexico High School Creative Writing Awards in 1961, a contest and publication that reached out to all New Mexico and Southwest regional high schools. It was a project that he directed for more than 25 years.

Because of his passion for sports, Erhard began announcing Aggie home games in football and basketball almost from the inception of his NMSU teaching career. He was in the press box for every Aggie home game from 1960 through 1995, four years after his official retirement from the faculty. To recognize his service NMSU inducted him into the Athletic Hall of Fame in 2006.

One of Erhard's most-treasured awards came in 1986 when he received Hofstra University's George M. Estabrook award to distinguished graduates, an honor shared with such luminaries as filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola.

Erhard is survived by his wife, Evelyn Madrid Erhard, three sons and their spouses: Danny Erhard and Sue Terebenetz; Larry Erhard and Kathryn Sayles; Bruce Erhard and Martha Lyle. The family has chosen Getz Funeral Homes for cremation services. Frank Thayer is a professor of journalism and mass communications at NMSU.

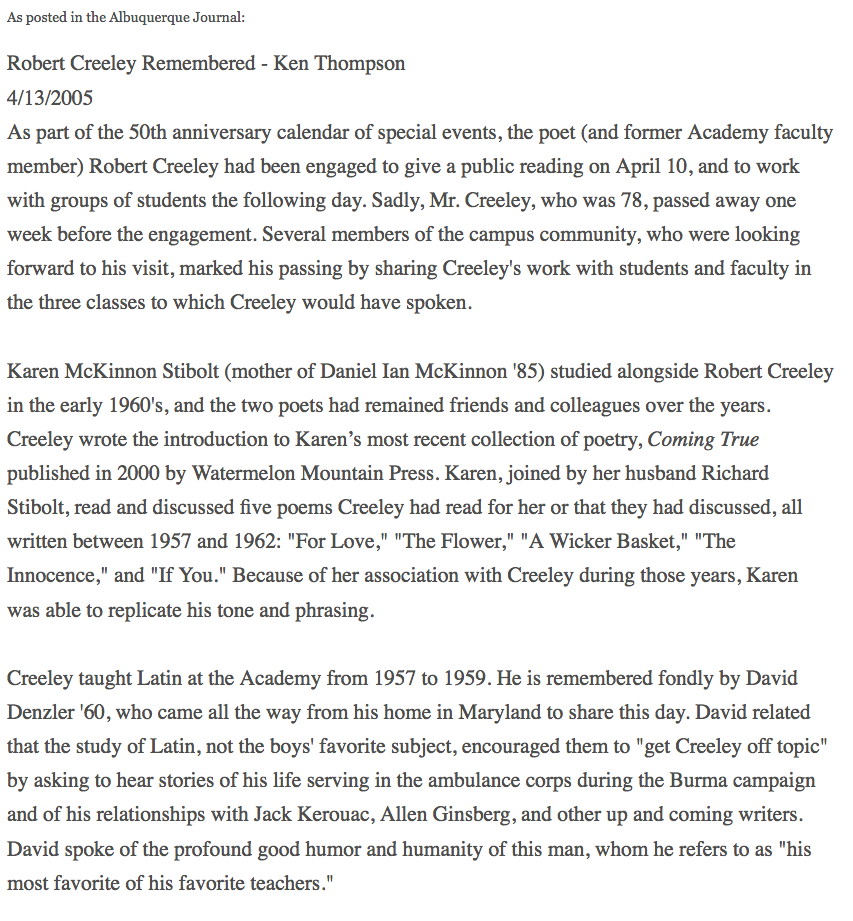

David Denzler graduated high school from Albuquerque Academy, a name often modified by the adjective "prestigious." It was a shaping force in his life, and he entertained us with stories about the goings on. His most often mentioned protagonist was his Latin teacher, and American poet, Robert Creeley.

David loved telling how he and his classmates managed, with little difficulty, getting Creeley off on one of his favorite topics, he was a man of myriad experiences and interests, instead of whatever the text had on offer.

The stories stayed with David, as seen in this 2005 article in the Albuquerque Journal

Robert Creeley (May 21, 1926 – March 30, 2005) indulged life like a hungry man going after the combination plate at La Posta in Old Mesilla. He grew up in Acton, Massachusetts, losing an eye at age 2, prepped for college at Holderness School in New Hampshire, attended Harvard, diverted to the American Field Service in Burma and India (1944-1945), returned to Harvard, did some chicken farming in Littleton, New Hampshire, taught school, and graduated from Black Mountain College in 1955. In 1956 he went to San Francisco and met Kenneth Rexroth, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. He eventually met Jackson Pollack in New York, but first went to Albuquerque where he met David Denzler while teaching Latin at Albuquerque Academy.

He earned an MA from the University of New Mexico, started a family, turned up in Vancouver and Berkeley for poetry readings and conferences, wandered here and there, and finally joined the "Black Mountain II" English faculty at University in Buffalo (1967-2003). He moved on to Brown University, other things, and finally became a resident of the Lannan Foundation in Marfa, Texas. In 2005 he was rushed to the hospital in Odessa, Texas where pneumonia carried him away. He's buried in Cambridge.

There's a lot more to the story, and you can find pieces of it linked from the pictures.

Just for fun, you could Google "Robert Creeley", and "David Denzler." You'll find that David has a folder in the archive of Creeley papers held at Stanford University. It seems to contain correspondence from the 1950-1997 period. I once asked David about it, but he was either noncommittal, or puzzled, I wasn't sure, and it was several years ago. Perhaps some bored grad student at Stanford will see this and go pull box 36, folder 1, and discover David's contribution to the written records of a great American poet.

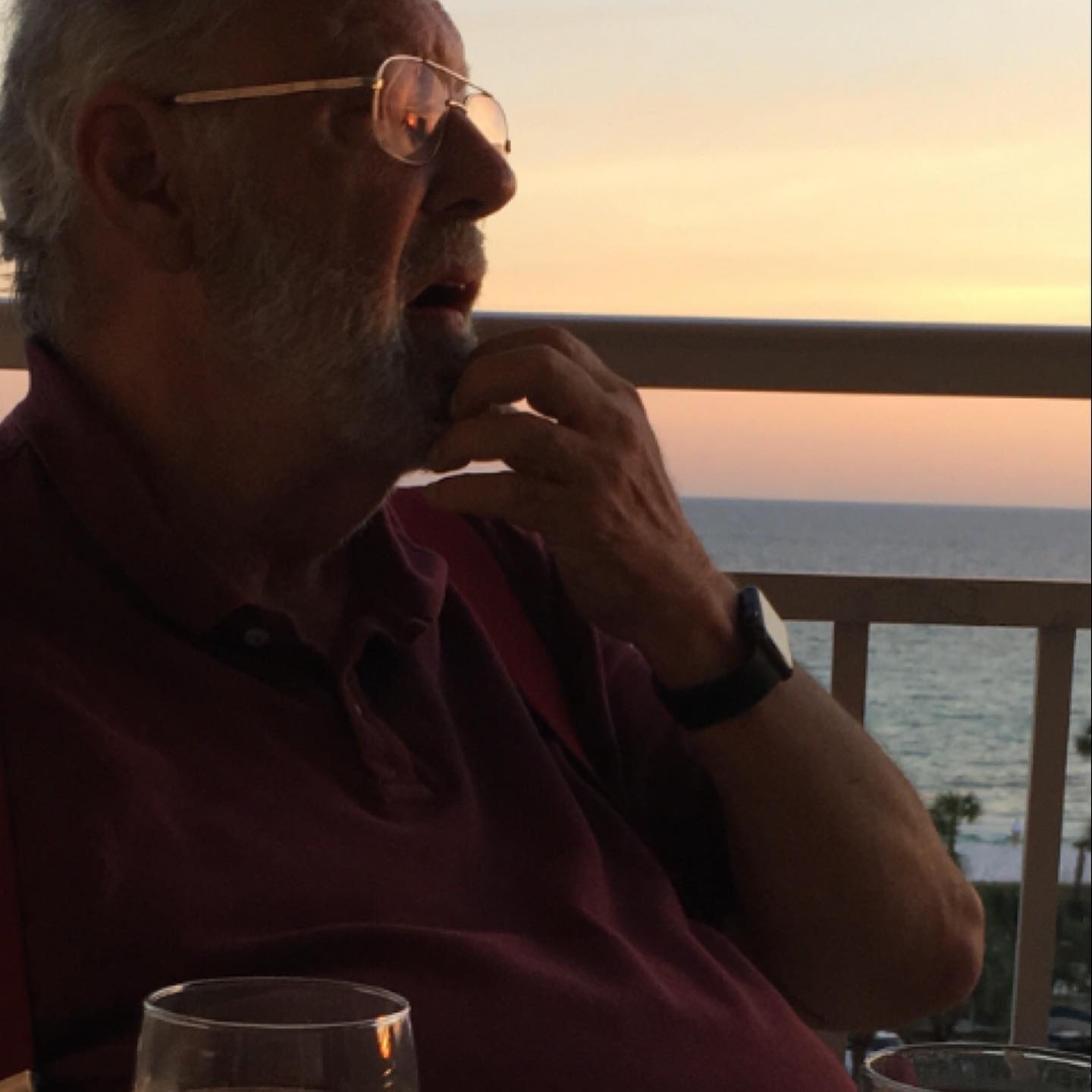

David Needham Sears

March 06, 1942 - January 13, 2021

David Needham Sears, 78, of Santa Rosa Beach, Florida, passed away on January 13, 2021 surrounded by his children.

David graduated from Crisp County High School and attended New Mexico State University with a trumpet and physics scholarship before traveling to Greenland and Denmark where he met his soulmate.

David loved with a full heart, laughed contagiously and was Einstein-level smart. He had an amazing career, traveled the World in creative ways and shared everything he had. He loved his children, adored his friends and family, and was passionate about animals of all kinds.

He was born to parents Needham "Pete" Hiram Sears and Sue "Mae Jewel" Bufkin Sears in Cordele, Georgia.

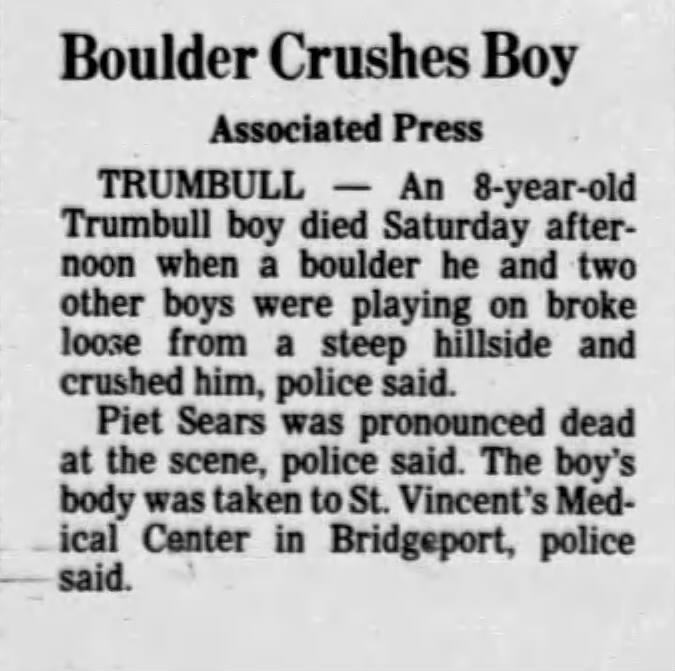

He is survived by his sister Susan Sears Lebold, brother-in-law Brian Lebold, nephew James Dorminy and niece Dru Dorminy as well as his children Michael Needham Sears, with wife Kristin Fians Sears, daughter Julia Teresa Sears, with husband David William Ambrose as well as a host of grandchildren and great-grandchildren: Abigail Rose Sears Palinski, Hannah Adina Sears, Joshua Needham Sears, Reese Annelise Ambrose, Quinn Else Ambrose, Cameron Piet Ambrose; great-grandchildren include Lorelai Anne Palinski and James Allen Braddy, III, plus two more on the way.

David's family will sail his ashes out to the sea so that all the people who loved David around the world may feel close to him whenever they are by the water. He will join his late wife and son, Annelise Jensen Sears and Piet Needham Sears in the ocean.

In lieu of flowers, the family would love to give back to the animal rescue that helped David find joy; donations can be made in his name to https://savewithsoul.com/donate

Dr. John G Kuhn III

June 2, 1935 - January 22, 2021

In January, 1961, I told a couple of friends that I'd drawn the worst possible prof for my second semester of Freshman Composition. David Sears's roommate had offered the same one-word assessment of a young instructor named Kuhn.

"Freshman Composition is an elimination course," David Denzler advised in that jaded, voice-of-the-wise tone he used when sharing his college acumen.

John Kuhn could trigger the terror of academic insecurity in young adults. For most of his students it was eclipsed by gratitude, but he had a memorable first-impression shtick, to use a term reserved to upper classmen in those days.

Mr. Kuhn, that first morning, dropped his brief case on the desk, and drew two boxes on the chalkboard. Everyone, he explained, is isolated inside a phone booth, the two boxes, and the lines are cut. Unable to communicate, we are alone and without significance. His job was to help us connect the lines. He told us to write three sentences for discussion in the next class, and I was pretty sure nothing I wrote would be adequate. Elimination loomed.

After about two weeks of this sort of thing, Mr. Kuhn asked a couple of us to remain after class. Uh oh.

"You two have nothing to gain from this class," he told us. "I want you doing independent study for the rest of the semester. Don't bother showing up here. Drop by my office, and we'll talk about some projects."

Mr. Kuhn was running a graduate-level seminar on W. B. Yeats, and he asked me to participate. I had a notion of having heard of Yeats, as one of the nineteenth-century "Thee and Thou" poets. I may have confused him with Keats. I figured it could have been worse. "Get this," he told me, holding up a copy of Yeats' Collected Works. I read it, and met every Tuesday morning with Kuhn and his grad students, an exhilarating, bewildering experience.

My best memory of the seminar has Mr. Kuhn reading and analyzing one of Yeats' more famous, later poems. "Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes, /Their ancient, glittering eyes, are gay." Perhaps the most important lesson I learned from John was how to think at the same time I was reading and writing.

I had no more classes with John Kuhn, but we became as friendly as instructors and undergrads can become, and we interacted from time to time. He advised me, gently, on my writing. He started a student literature contest, and encouraged me to enter. At the end of the '61-'62 term John called me, told me he was leaving, and asked for help.

My memory always had him transferring to the University of Texas in Austin. He asked me to pitch in with the driving. I turned him down on the flimsy excuse of leading a math seminar that summer. I could have worked it in, and he knew that, and he knew I knew it. I refused, John disappeared, and we never communicated again.

I've remembered John Kuhn for over sixty years, and tried a couple of times to reconnect, but, alas, without success. Those telephone lines had stretched a bit too far, for too long.

The University of Texas recollection was apparently a false memory. I now find he finished his PhD and made a career at Rosemont College, filled with just the kinds of accomplishments I'd always assumed for him.

I'm sorry to hear of his passing, but gratified to get a glimpse of the life I assumed he was leading. It is exciting to rediscover the man through his subsequent life, and to learn that I was one of many who considered him a seminal influence, academically and spiritually.

My undergraduate self didn't realize how rare it would be to brush up against a master, and how fluidly the present becomes the quick-dry concrete of the auld lang syne.

John G. (Jack) Kuhn, III, PhD, died peacefully at his home in Ocean City, NJ, on Jan. 22, 2021, after a long illness. He taught English, writing, poetry, and theatre at Rosemont for 30 years.

John was born in West Philadelphia, June 2, 1935, to John G. II and Helen (Wright) Kuhn. After graduating from West Catholic High School in 1953, he earned his BA in English from St. Joseph's College (1957) and his MA in English from Purdue University (1959), where he also met the love of his life, Janice Rose McFadden, a math student there. The two married in 1960 and lived in Las Cruces, NM, where he taught at New Mexico State University before returning to the Philadelphia area to complete his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and begin a 30-year teaching career at Rosemont College.

He taught English, writing, and poetry and developed the Rosemont theatre program, directing an annual student theatre production before retiring in 2002, becoming Professor Emeritus. He was a dedicated writer and throughout his career published poems, plays, and scholarly papers on Greek theatre, Walt Whitman, and Eugene O'Neill. Everything - his family, nature, politics, world crises - became fodder for his writing. In particular, his year-long sabbatical in Montalcino, Italy, inspired a volume of poetry, Some Stolen Pavingstones.

John's home office, overlooking the Pennock Woods in Lansdowne, PA, served as his writing haven. Most days, when not at Rosemont, he would be found working at his old typewriter and smoking his pipe in his office, a den too small to move about and overloaded with hundreds of books he had collected (and read) and sorted into wooden boxes alongside scores of playbills, notes, clipped articles and class outlines - all stuffed into its proper book.

John loved teaching and for 37 years relished introducing students to the joys and mysteries of literature, poetry, and theatre. He was highly regarded by colleagues and by students who, decades later, spoke lovingly of his influence and inspiration. In addition to his wife of 60 years, John Kuhn is survived by his children, John IV (Suzanne Flynn), Kirsten Campbell (Jed), Gregory (Gillian Thackray), and Claudio (Jami Fisher); grandchildren, Connor and Dylan Campbell, Kara Kuhn, Annalise, and Elias Kuhn; step-grandchildren, Jack McMahon, Conn, Aine Twomey, and Evan Clark; sisters, Nancy Kirkpatrick (Douglas) and Mary Kuhn; brother, Frank Kuhn (Karen); sister-in-law, Joan Kuhn; and numerous beloved nieces and nephews.

How does one write about a writer? This quandary would have fascinated our friend, Dr. John G. Kuhn III. I wonder will he begin this task by uncapping one of the myriad red pens that nestled so snuggly in the pocket of his tweed blazer? Once I’ve submitted my work, will he take points off for not citing my sources? Will my thesis be evident and effective? Or, will he tell me to dig deeper? . . . because “You can do better, Tara.”

Once tasked with this project, I made haste to the basement as I knew exactly where my Rosemont files were located. I had saved all of my English papers on the off chance that someone would ask me for “A Critical Analysis of Oedipus Rex.” Before I delved into that dilapidated, dusty box, I was quite certain that John Kuhn gave me an A in every course over our four years together at Rosemont. Well, I was wrong--(unreliable narrator)! Many of my papers were a minefield of red ink, cross outs and suggestions. On one paper, I actually received an A/D+. How is that even possible? Is it an A, John? Or a D+? And if it’s a D+, I may need to choose another advisor.

As a poet, a writer and a director, John Kuhn loved the written word. He embraced it, he labored over it, he loved to talk about word choice. As the longtime director of Jest and Gesture Theater, it was, “Call me John.” Well, that was a word choice. It meant: I am your friend and I care about you. John Kuhn cared enough to push me to be better. To not be satisfied (split infinitive and sentence fragment) with my first draft. He loved the theater and encouraged his students to trust and to take risks. Through his rich life, John impacted scores of thespians with his knowledge, his wit and his care. He saw his students as the best version of themselves and pushed them to take risks to achieve this.

Here’s what I learned: The difference between its and it’s. Finally! I wrote it on the inside of my folder and think about that once or twice each day. And I thank him because not a lot of people know that one. I promise. Look for that error in your daily life and you will find it. A good writer will “Show it, and not say it.” Because if you show it correctly, your reader will understand. Here was his example: I know my son loves me when he wants to introduce me to his friends. He doesn’t have to say it, he doesn’t have to hit me over the head with it. I know it’s there because of his gesture. (Notice the correct use of it’s.)

And I know that scores of thespians (remember them from paragraph 3?) knew it too. He invited them back to Rosemont to be a part of J&G long after graduation. He kept them as a part of Rosemont Theater as audience, as judges. An ever-evolving group of dedicated and loyal players who kept coming back because of the caring world that John created with his co-director, Meg Walters.

All of the papers that I wrote for John were lovingly critiqued. Perhaps John Kuhn put more effort into the critique than I actually put into writing some of those early papers. Probably, yes. As I read over his comments, I realize that he was showing me his care and friendship even if I didn’t always like the grade. And that minefield of cross outs were always signed “Love, John.”

MusicWorks mourns the passing of a dear friend, colleague, mentor and supporter, Dr. John G. Kuhn, III.

An inspiration to Mr. Jerry, MusicWorks Director of Music Therapy and many successful actors, actresses, musicians, professionals and students in all walks of life. John spent his entire teaching career at Rosemont College and started the Jest & Gesture Theatre Department during his tenure.

John was a writer, poet, teacher, father, husband and a true inspiration to all who had the privilege to know or work with him.

MusicWorks shares its condolences with his wife, Janice, and his children, John IV, Kirsten, Gregory and Claudio, as well as John's entire family. God bless you, John and we look to the day when we will all be reunited on the Heavenly stage.

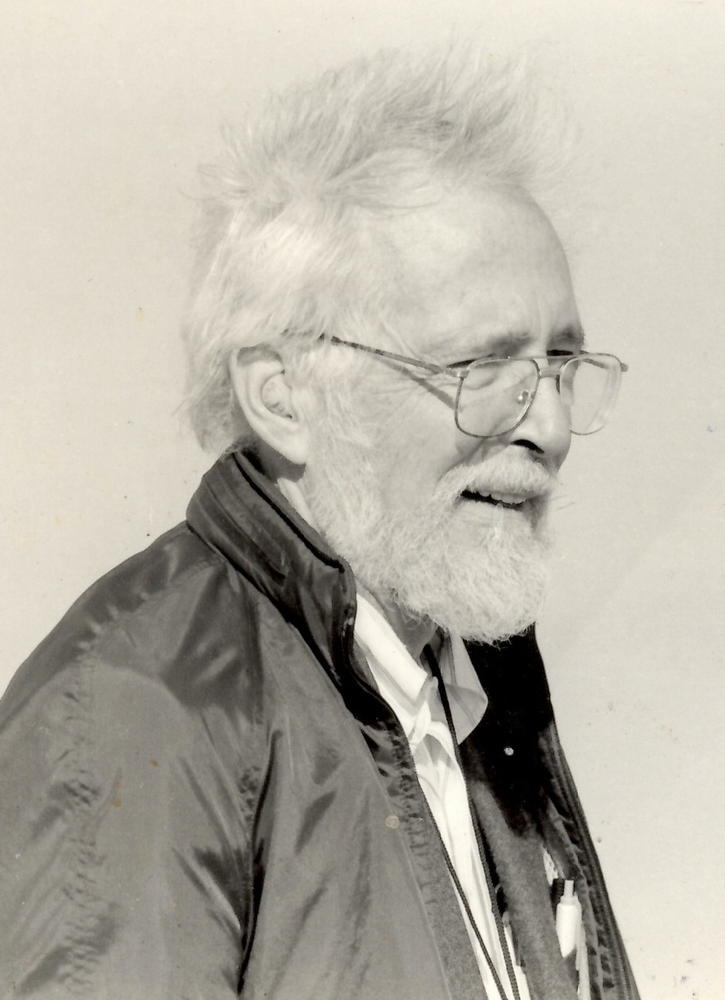

David W. R. Denzler, in His Own Words

23 October 1942--6 May 2019

"[I] went back to the academy to see Bob Creeley only to have him pass away a week before. I went anyway so that I could tell some of the students what he was like. I also went down to Cruces to see Tom Erhard. I hadn't seen him for 10-15 years."

"I lost touch with just about everyone in the years back in Maryland. I used to do quite a bit of travel and looked for Dave in Anaheim on several trips out to CA, because Tom had said that Dave had dropped out of school and went to Anaheim when I was on work phase in 1961-62. Tom is the only NMSU contact that I've kept in touch with."

"My NMSU alumni directory arrived …. And Farris Bakki is in it! I was so pleased that he is still alive - I've worried about him for years. After he had graduated, he kept in touch with my folks for a few years. He went back to Iraq for a while but then ended up in Paris. He called me once, but,….the phone number I had was no good. I took Caroline to Paris in 1995 and tried to find him in the Paris phone books with no luck. I intend to write him soon. Anyway, he now lives in Jordan."

"You may already know some of this stuff - my memory of events and their narration from 40 years ago isn't always precise. When I came back from my work phase at Applied Physics Lab of Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in Sept 1962, I was rooming with[...] and I think you were next door. Then I had the ankle rebuilding surgery over Thanksgiving which, after a fairly long recovery, accomplished it's goal of getting me out of the hated steel brace.

" It was good till two years ago, but the new braces are so much more comfortable that I don't mind it. Caroline came out at Christmastime to visit and decided to stay. She was still dancing at the time and danced with the El Paso Civic Ballet…she started teaching in Hatch, Montecillo and Deming. We got married in Oct 1963.

"Even before we got married, I dropped out of the coop program so I wouldn't have to desert her for something like that. For the rest of my time at NMSU I worked ~20 hrs a week at PSL tracking satellites on the top floor of the Library.

"I…graduate[d at] the end of summer of 1964. The early fall of 1964 was not a good time to be looking for a technical job -everybody was afraid that peacenik Johnson would get elected and all the defense jobs would go down the drain - so much for predicting History!

"The only job I could find was at APL thanks to the good words from the guy I worked for as a coop student, and the fact that they knew I could write because of my Puerto del Sol experience. If I'd tried to get hired on the basis of my grades, I wouldn't even have been able to get a janitor job there!

"My first job there was to monitor torpedo fire control testing on Polaris subs at the Cape - of course to write reports of what happened was the primary skill required. I'd go down for 2 weeks out of every 6 for nine months of the year. That really blasted any attempts to get more formal education….

"Caroline…went to college for a couple of years, but gravitated back to teaching ballet to very young kids….Several years ago Dover books invited her to write text to explain the pictures of ballet classes in a coloring book. They keep reprinting it and we still see it in the gift shop of the Kennedy center. So she became the writer and I didn't.

"… from the days on the black cigar [I] was…awarded my own honorary submariner dolphins by the enlisted men and petty officers – as far as I know, I was the only APLer who had that honor. I did also tell the Captain of a sub "It's your boat Captain and you can do anything that you want with it - we just want to watch." I didn't get a raise for 18 months because of that, even though I really was just talking about our data collection role during some impromptu war games.

"After a couple of years on the black cigars, I finally got a transfer to the Space Division where I stayed till 1980. Almost all of my work was on ground systems that worked with the Transit Navy Navigation System, the predecessor of GPS. I worked my way through school tracking the research version of Transit before it became operational in 1964. It stayed in service till 1996.

"At it's height it provided navigation services to several hundred thousand boats and ships of which only a few hundred were navy ships that paid for the operation and maintenance of the system. I got to system engineer the first civilian prototype - it was great to help cast the swords into plowshares.

" I got some great trips out of it – riding on bridges of merchant ships to Panama and Puerto Rico, giving papers in SF and St. Pete and the boondoggle of true fantasy - operating equipment for the BBC to film in Arles, France for the first "Connections" series. For somebody who really wanted to get into film - remember, I took Wanzer's first film course- I practically was in orgasms for the week I got to watch them make the film.

"As you may recall, the economy wasn't real great in the late 70's, and APL, as a nonprofit limited in income by congress, wasn't increasing salaries at anything like the cost of living increases. We really wanted a house on the right side of the tracks and got tired of waiting for someone to die or retire to get a raise or increase in responsibility, so I decided to switch to a commercial company. So, I went to work for Computer Sciences Corporation at a 30% increase.

"It was different going to work for a subcontractor to NASA where we didn't have the freedom to fail as we did doing the R&D at APL. CSC's management sucks, but they have enough sense to leave the workers alone and I've had a pretty good time with my coworkers.

"I worked on a lot of Goddard Space Flight Center's ground systems until we lost the contract. I spent a few crappy years on contracts to the IRS, USAID and doing proposals, but finally ended up on a contract to the FAA that is bound to last more than the 3 years and 2 months till I retire (but who's counting).

"I know that it sounds like I hate my job, but I don't really hate it - it's just that, with age, I've found that my tolerance for the politics and internecine interoffice warfare has gone to zip, and it's really hard to have a job in this profession without them taking over.

"I never thought that I'd want to give up systems engineering, but find I'm not minding passing it on to the younger ones any more - they certainly are more caught up to the technology than I am.

"I never did become the great poet or great fiction author. Maybe someday I'll try nontechnical writing again, but I've found something else to do to sap up my frustrated creative juices. About 20 years ago I had to have my ankle rebuilt again and had a really slow recovery - over a year. It wasn't expected and my watch spring was really wound tight.

"That summer Caroline said "I hear the tri-county Arts center has classes in bronze casting - maybe you should try it." I'm sure she was trying to get me involved in something to distract me from my problems, but she was really starting an addiction that I still have today. I now work in bronze, wood, clay and fiberglass - about half are realistic portraits and the other half are sort of caricatures.

"We really haven't decided what to do about retirement….We have thought about coming back to New Mexico, but still have over 3 years to procrastinate! By and large we're in reasonably good health (knock on wood), so that's not a constraint now."

"I only write papers when I get a decent trip. Of course I did have to coauthor another paper for that conference with the NASA COTR in order to get the funding for the trip. I let him write two sentences. Being a sub to Lockmart for the last 7 years has put a real crimp in paper opportunities. The paper you referred to was done because I already had the trip to Oxfordshire ( I seldom add the "shire" when I tell others about where I've delivered papers) set up. The whole concept was hatched over one too many glasses of wine one night. Must go - with only 480 days left to full Soc Sec, and I thought I could stay under the proposal body sucking radar, but they found me anyway."

"My co-op work phase and tracking stuff at PSL turned into 15 years at Applied Physics Lab of Johns Hopkins U back here where I got to work on early satellite navigation stuff. Then, however, during the late 1970s congress put a dollar limit on APL/JHU when inflation was skyrocketing, so I went to work for CSC. Not nearly as fun ("Zero Defects", etc.) but I've eaten well since.

"Anyway, the last couple of years has been quite busy due to a rare brain condition called superficial hemosiderosis for which I had to go to the Mayo Clinic for diagnosis in Feb 2007 and then for back surgery in Nov. I was out of work till Dec 31, but have now returned and supposedly counting down the 186 days [to retirement']."

"Well, I finally retired as of Oct 23, my 67 th birthday. As I was warned, being retired means you are busier than when you worked!

"Caroline is really astounded that I don't miss the work; I guess I'm really ready to expend my energies in other areas. Perhaps it’s because I tried to stay out of management and become a systems engineering guru and even though the principles have remained the same all these years, the softheads have kept inventing new “methodologies” that haven’t improved productively but give them a language to protect them from “technical intruders.” I swear I’m not a bitter, outdated, old man! I just didn’t want to learn a new language.

"We did a bit of canoeing before we had to bring in the canoe and kayak for the winter. It was good since I hadn’t been able to this summer because of a broken arm, and it was probably the best summer we’ve had since we moved here. I've been working in my sculpture studio to upgrade it for doing more of the prep work for bronze casting but that has been curtailed by the weather and Christmas. Boy, every day is like Saturday, and I don't think I've gotten up "on time" more than once or twice since I retired."

"This will be short as I'm having to type it hunt and peck with my left hand. Friday night I fell and broke my right arm between the elbow and shoulder. The bone doc wants to add a bit of steel next week, so it's going to be at least a month till I'll be able to write you all with both hands.

" I had surgery Tuesday and the Doc has recognized my Tooltime TV show Tim Allen tendencies and put in a stainless steel plate and 11 (at least ) screws. I had told him I am so klutzy I was sure I'm going to be seeing him again. I think he was so proud of his work that he had the hospital take some X-rays before I left. Maybe he's going for the Guinness book of records!

"At any rate, he did a great job and already today - 2 days later - I can type with my right hand!

David's health problems overtook him in 2013, and he passed away in 2019. He left behind so much of himself, it seems churlish to complain of the surpassing gap of his leaving.

I still have the tapes Dave Sears and I made of his ancient record collection, and hearing them connects up some old memories, but the music is just a click away.

Magic in the Desert

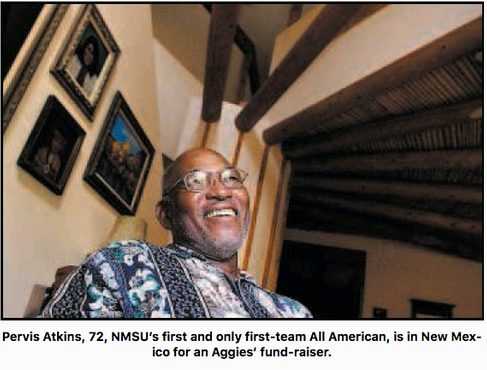

In those days it was common for young men to join the service out of high school, and attend college later. Several of these veterans lived in White Rock, and considered the accommodations upscale. One NMSU alumnus, Pervis Atkins, who was part of the undefeated Aggie football team of 1960, lived a while in White Rock. His picture at right links to a remembrance of his experience. Here is how the barracks were described in a history of the NMSU agricultural department.

"Right after the war, when veterans were returning, they were given priority for jobs. Since Ralph Skaggs was not a veteran, he was invited to make way for a veteran to run the State Experiment Farm in June 1946. He immediately called Professor Cunningham and asked if the faculty position was still available. Since many veterans were being discharged and wanted to go back to school under the GI Bill of Rights, this proved to be a very good change in jobs. During the war the dairy department had an occasional student from some country other than the U.S., who pursued a degree in animal husbandry and required a course in dairying as part of the curriculum, but no U.S. citizens were ever enrolled in the department during these years.

"The first dairying class in the fall of 1946 contained fifty returning GIs where there had been almost no students in the previous four years. The campus was swamped with GIs. Old army barracks buildings were moved in and used as student housing. Married GIs were placed in small trailers. Both temporary types of housing were located along the south edge of the campus. Some of these came from the construction town of White Rock, NM, near Los Alamos. They were named White Rocks barracks and given the number corresponding to their building number when used in White Rock."

Let's not forget, 1960 was the year of Magic in the Desert, the undefeated season for the New Mexico State Aggies Football team. To a freshman it seemed the natural order of things. It wasn't. Click the picture for a review of the book written by those who witnessed it.

Dan Perry, Journalism Major, was a junior in 1960 when the heretofore and hereafter hapless Aggies had their undefeated season. He wrote a book about the fabulous experience. It was published posthumously by Frank Thayer and other friends.

And while we're thinking about sporting events, let's not forget the first annual literary awards, sponsored by John G. Kuhn, my freshman comp teacher, in his second, and last, year at NMSU. The top prize went to fellow math major, Jimmy Johnson (called J-squared, of course). Dave Denzler and I both won prizes, but we weren't roomies by that time. See the pop up link at left.

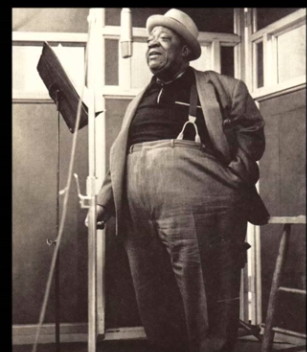

Meeting Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who'd been somehow co-opted by Kuhn to pass out the awards and read his poetry, was another of those undergrad experiences that seemed one-in-a-long-string until the string proved very short.

His appearance was impressive, and we're lucky it was memorialized by competent observation. All I remember about Ferlinghetti's talk was his dismay with Ernest Hemingway, who'd recently shot himself. Lawrence, head Beat at that time, at least on the West Coast, dismissed Hemingway for not engaging the politics of pre-Castro Cuba in his latest book, "The Old Man and the Sea." Oh well.

Monday, June 09, 2008

Aggie Football Legend Atkins Returns To N.M.

Aggie Football Legend Atkins Returns To N.M.

Journal Staff Writer

Pervis Atkins grew up in Oakland, Calif. He’d been a Marine. He’d been on site in Nevada for testing of a nuclear bomb that, when detonated, created a flash so bright “you couldn’t see from here to there,” he says, pointing to his friend Charlie Rogers, sitting attentively on the other side of Rogers’ living room.

All of that tested his toughness, but in no way quite like his first night at New Mexico State, nearly a half-century ago.

Atkins was on a football recruiting visit with Bobby Gaiters, a much more heralded high school star from Ohio. Their night’s stay was in converted Army barracks moved on campus to help house an influx of students.

At night, cows were let loose to roam right outside. The mooing all night and manure in the morning didn’t sit well with a city guy. “White Rocks, they called it. Boy did it stink,” he says, laughing. “I said, ‘We can’t stay here.’ ”

But he did. Gaiters did. And Atkins, now 72, was soon to go from an unknown to one of NMSU’s greatest players ever — the nation’s leading rusher (971 yards in six games) and punt returner (15.1 yards per) in 1959; the school’s first and only first-team All-American the next year.

“I was ‘the dog,’ ” he says, laughing.

Atkins and, especially, then-quarterback Charley Johnson represent ties to the days New Mexico State football had its swagger, when victories over the Lobos and Miners were convincing and expected. They led both victorious Sun Bowl teams, in 1959 and 1960.

The latter team went unbeaten and was the subject of a Sports Illustrated cover story — “The Team The Pros Watch,” Rogers recalled — for all of its NFL prospects playing in far-flung Las Cruces for Warren Woodson.

The Aggies, alas, haven’t been back to the postseason since and currently bear the burden of the nation’s longest bowl-less streak.

Atkins went on to play parts of six seasons with the Los Angeles Rams, Washington Redskins and the Oakland Raiders. He settled in Los Angeles after his retirement and went into the talent agency business.

And he thought many of his athletic exploits had been forgotten until this past spring, when he was one of 75 nominees for the 2008 College Football Hall of Fame class.

“Totally, totally it blew my hat off my head,” Atkins said. “I said, ‘Somebody’s b.s.-ing me down the road.’ ”

He wasn’t one of this year’s eventual 13 selections — Troy Aikman and Thurman Thomas among them — but has a chance for future consideration.

Atkins is part of the weekend revival of the Aggie Nation. Boosters met Saturday night at an athletics fund-raiser in the Albuquerque home of Larry Lujan, president CEO of Manuel Lujan Agencies and an Aggie alum.

Today, boosters and alumni are gathered to play golf in the Fourth Annual Aggie Shootout at Rio Rancho’s Chamisa Hills Country Club. While Atkins will be golfing in a field including NMSU athletics director McKinley Boston, football coach Hal Mumme, basketball coaches Marvin Menzies and Darin Spence and the like, his friend Rogers, one of the city’s most active NMSU athletic boosters, is running the event.

Atkins and Rogers met when Rogers was working in the school cafeteria.

“Back then, the enrollment was 26, 28 hundred and the student body was very cohesive,” said Rogers. “Within a few weeks you felt like you knew everybody on campus.”

It’s a friendship that has maintained through the years. The two can call each other and within minutes they’re laughing at stories of the glory days, though in their time at NMSU, the glory days were really glorious.

“He’s my brother,” said Atkins.

Others in the Cast

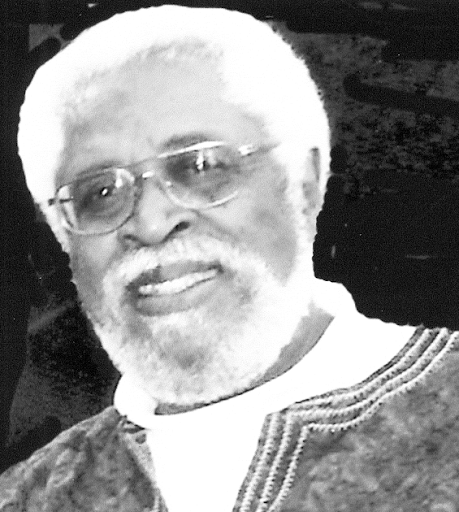

There were other significant freshman influences, mostly positive, the more remarkable for seeming ordinary at the time. There was Stanley Puryear, math instructor, who, being black, informed my assumption I'd reached an airy height of social maturity. I didn't realize the rarity of black instructors, then and for years after. Mr. Puryear revealed the beauty of mathematics like a Pythagorean initiating his iron-age novices, then went on to an inspiring career in writing, civil rights, community activities, and academia, with stopovers in Aerospace. He is now Muata Weusi-Puryear and has been inducted into the Distinguished Alumni Hall of Fame at Asbury Park High School, Asbury Park, New Jersey. My old math teacher has filled his life with passion and accomplishment. Salute, old friend.

There was also my first-semester Freshman Composition instructor, Peter B. Walsh, who demonstrated the pathological depths of eccentricity required to pass as a rare bird in the Beat Era. He'd been the editor of Pen, the literary magazine at the University of Utah, and had published in Poetry Magazine. The poem was anthologized as one of the best of 1955, the year Emmett Till was murdered. He was active in the campus theater, Shakespeare's Caesar, and some avant garde stuff, and seems to have had a voguish politics, think Dr. Strangelove, signaled to his classes by his assertion, hardly credible even to a freshman from the sticks, that the Civil War hadn't been fought over slavery. The poem links to a few letters to the editor, included not for edification, but as reminders of the dernier cri of the time. But I learned most of this later, after the culture that birthed the poem had long evolved. Peter disappeared without a trace as far as I can find.

John G. Kuhn, my second semester composition instructor, introduced me to W. B. Yeats, analyzing the famous Irishman's poetry with an expository crispness never elsewhere encountered. His analysis of Lapis Lazuli is the only one I've found that treats the theater allusions.

Kuhn once invited me to his house, and admonished me for complimenting his wife on her coffee. He threatened to flunk me if I ever dropped another possessive apostrophe. I did and he didn't. Good man.

Kuhn was a ruthless critic, the only valuable sort. He disappeared in my junior year, memory suggesting a migration to the University of Texas, but now I find he went on to a career of academia, literature, and dramatic artistry at Rosemont College. He was theater director for years, and is now retired. There must be, by this time, a cracker-jack diaspora of Kuhn-trained thespians, masters all, I'm sure. They probably have a secret handshake.

Before majoring in math I felt called to physics, but shortly abandoned the frictionless planes, and weightless strings for the ephemeral certitude of axiomatic logic. I hadn't heard of Kurt Godel yet.

I had to explain myself to this gentleman, a much-admired inspiration for young scholars. I couldn't tell him a truth I hadn't admitted to myself. Math was eating popcorn and physics was chewing nettles. I just wasn't up to it, and always felt I'd let him down.

I eventually got around to a few other poets, but Yeats remains my mysterious force. No one does a very good job of reading him, but it's hard.

Undregrad Symmetry

In the 1960s New Mexico State University became a force in a branch of mathematics called Abelian group theory.

Group theory became important in Physics because of its methods in handling symmetries. Abelian groups apply to a special type of symmetry found in current models of reality. But, the theoreticians assembled at New Mexico State University were not working on the application of Groups. They were stimulated by aesthetic allure.

One of the Abelian Group Theorists to arrive in Las Cruces in 1963 was Dr. David Harrison, on leave from the University of Pennsylvania. He was among that rarest of sightings for amateur Prof Spotters, the research fellow who teaches undergraduates. A friend and I had the pleasure of taking an advanced algebra course from Dr. Harrison. Besides being an excellent teacher, able to articulate complex concepts, he was a high-energy entertainer. He became "Hurricane Harrison" to us. Nicknames for professors were normal. There was H2O, aka Howard O. Smith, the Chemist, Tugboat, the rotund and languorous physics prof who chugged into class puffing a pipe, and "29," the econ prof who began and ended every paragraph with the great depression. These names normally stayed within student control, but my friend once slipped in a conversation with his adviser and referred to "Hurricane." He was rewarded with the enigma of a mathematician's smile.

The Abelian Group episode at NMSU was exciting from the periphery of undergrad status. There were international conferences that anyone could attend. My friend made another rare sighting, a slender fellow with a beard to his navel, and identified him as, "the original Abelian Group." One of the Abelian forces was Dr. Elbert Walker, an object of special admiration to us because he had a beautiful wife who was also a mathematician. In fact, Dr. Carol Walker was, years later, the head of the department. The Walkers, Harrison and others were among the young, energetic PhDs on campus who gave NMSU such a vibrant ambience in those days. He has written a synoptic history of the Abelian group days, and you can access it nearby.

After graduation David Denzler, my old roomie, married his dream girl and made a singular life with accomplishments unique to him. I suspect he was always a mentor. I suspect there is a broad wake of friends, current and former, who share my appreciation of his leadership.

When I think of him now, I think of the famous quote from Fats Navarro, jazz trumpeter of the 1940s, who said, "I'd like to just play a perfect melody of my own, all the chord progressions right, the melody original and fresh -- my own." That was Dave.

My old roommate of the White Rock days passed away recently (David WR Denzler: October 12, 1942-May 6, 2019), a truth weighted with unexpected emptiness. Our life journeys never steered within hailing distance, even though we worked for vigorously competitive rivals. I saddled up with Telecomputing Services Inc, thanks to a family friend, Jim Rucker, whose father happened to run an employment agency. I rode with the company for decades, through its many incarnations and cattle drives. David's employer, Computer Sciences Corporation, was a nemesis of ours, too often a step ahead in must-win competitions. I didn't know David worked for them until much later. But he was in the set of my hat, the grip of my reins.

David was a shaping force in my life. His significance far outweighed the short time I spent with him. He was a model of confidence, endurance, even exuberance. He failed as often as anyone, but David had a peculiar confidence in ultimate success. He never doubted it. If his car broke, he had a plan. If he failed a test, he learned why. Every moment changed him a little, but he was always his own person, making adjustments on the fly, confident he'd get there. A typical memory involves lunch in the cafeteria during "Sadie Hawkins Days," the post-Al Capp generations can look this up, when Dave put a hand-lettered sign on our table, "Notice! Still Available!" I couldn't have had a better freshman roommate.

Youth demands its monuments. Our remembrances of youth remain perplexing, urgent, in need of memorializing. An earlier alumnus of what is now New Mexico State University, Michael F. Taylor, accumulated a hoard of memories from 1935 to 1939. He fetched them to pen and paper years later under the title, "The Glory Years.”

White Rock Barracks barely survived our tenure at NMSU. The flashy new Regents Row that replaced them is now gone. The university, indeed the world, has passed into, and largely out of, the hands of our generation, and nothing seems the same. Yet, that autumn glow of slanted sunlight reveals the truth; the only change is the modest tampering we did on our passing through.

Who in the world cares about White Rock Barracks?